When I converted my vegetable garden to no-dig methods twelve years ago, I thought I’d discovered the perfect solution to decades of back-breaking spring preparation. The concept seemed foolproof: layer cardboard and compost, plant directly, and watch everything thrive without ever turning a shovel. Reality proved more complicated. Within weeks, I faced weeds pushing through gaps, slugs devouring seedlings, and soil that seemed to sink and compact despite my best intentions. I almost gave up and returned to traditional digging. But I’m stubborn, and I’d invested too much cardboard and compost to quit without understanding what went wrong. Over three seasons of careful observation and adjustment, I solved every challenge that no-dig gardening threw at me. Now my beds are the most productive I’ve ever maintained, and I want to share exactly how I overcame each obstacle so you can skip the frustration I experienced.

Why No-Dig Gardens Face Unique Challenges

No-dig gardening works beautifully once established, but the transition period creates problems you won’t encounter in traditionally worked soil. You’re asking nature to do work that gardeners typically force through mechanical cultivation. Earthworms need time to move in and create channels. Beneficial fungi need seasons to establish networks. Soil structure needs to develop through biological activity rather than physical manipulation. During this establishment period, which typically takes two full growing seasons, you’ll encounter challenges that can feel discouraging if you don’t understand they’re temporary and solvable.

The problems also arise because you’re creating a fundamentally different growing environment. Traditional tilled beds have bare soil exposed to sun and air. No-dig beds maintain constant surface coverage with organic matter, creating habitat for both beneficial organisms and potential pests. The permanent mulch layer conserves moisture wonderfully but also provides shelter for slugs and creates conditions where some diseases can thrive if not managed properly. Understanding these differences helps you anticipate challenges and implement solutions before minor issues become major frustrations.

Problem One: Persistent Perennial Weeds Breaking Through

Why Tough Weeds Defeat Standard Cardboard Layers

Bindweed, quack grass, Canada thistle, and nutsedge have evolved to survive adverse conditions through deep, persistent root systems. A single layer of cardboard and four inches of compost won’t stop them, no matter what enthusiastic no-dig videos suggest. I learned this watching bindweed tendrils spiral up through my carefully constructed beds just three weeks after planting. The weed had simply pushed through a small gap where two pieces of cardboard met, found the light, and spread across the surface within days. Standard cardboard coverage works perfectly for annual weeds and lawn grass, but perennial weeds require more aggressive suppression.

The problem compounds when you don’t know the weed species you’re dealing with. I once established a beautiful no-dig bed over what I thought was just crabgrass and dandelions. Within a month, I had Jerusalem artichoke shoots emerging everywhere, remnants of a planting from years earlier that I’d forgotten about. Those tubers sat eighteen inches deep, completely unaffected by my surface cardboard layer, sending up vigorous shoots that easily penetrated six inches of compost. If you’re converting an area with unknown history or visible perennial weeds, assume the worst and plan accordingly.

The Solution: Extended Smothering and Triple Layering

For beds with known perennial weed problems, I now use a triple cardboard layer with newspaper sandwiched between each cardboard sheet. I overlap all edges by eight to ten inches instead of the standard six inches, creating an impenetrable barrier. More importantly, I establish these beds in fall and let them sit through winter before planting in spring. This six to eight month smothering period exhausts root reserves that would otherwise push through. I add eight inches of compost initially instead of the standard four to six inches, ensuring any weeds that do emerge have to travel far enough that I can spot and remove them before they photosynthesize and rebuild strength.

When perennial weeds do break through despite precautions, immediate removal is critical. I check beds every three to four days during the first growing season, pulling any emerging weeds before they develop more than two or three leaves. Each time I pull a weed, I add another inch or two of compost directly over that spot, making it harder for the next shoot to reach light. This consistent suppression eventually exhausts even bindweed and quack grass. By the end of the second season, emergence drops to nearly zero as root reserves deplete completely. The key is never letting emerged weeds photosynthesize long enough to replenish those underground energy stores.

Problem Two: Excessive Slug and Snail Damage

Why No-Dig Beds Attract More Slugs Initially

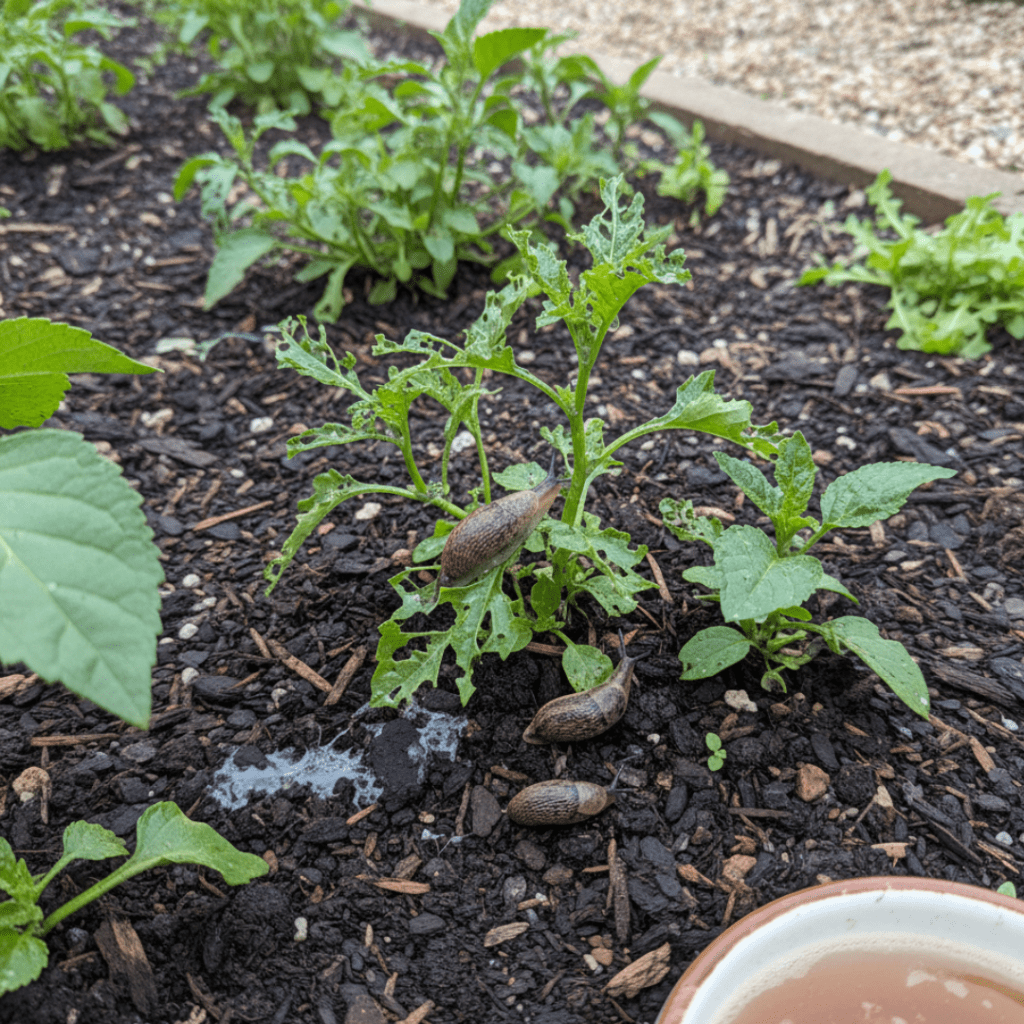

The permanent mulch layer that makes no-dig beds so effective at moisture retention also creates ideal slug habitat. Cool, damp conditions under compost and decomposing organic matter provide exactly what slugs need to thrive and reproduce. In my first no-dig season, I watched slugs completely defoliate an entire planting of lettuce seedlings overnight, something that had never happened in my tilled beds. The problem was worse in my shadier beds and during wet springs when moisture levels stayed consistently high. I initially tried copper barriers and diatomaceous earth, but these proved ineffective once rain compromised the barriers or wet conditions rendered the diatomaceous earth useless.

The slug population explosion is temporary, but that’s cold comfort when you’re losing transplants and seedlings weekly. The surge happens because you’ve suddenly created favorable habitat without yet establishing the predator populations that will eventually control slug numbers naturally. Ground beetles, firefly larvae, garter snakes, toads, and birds all feed heavily on slugs, but these predators need time to discover your garden and build populations. In traditionally tilled gardens with bare soil and fewer hiding places, slug populations stay lower because habitat is less favorable even though predators are also less numerous.

Short-Term Management and Long-Term Solutions

For the first two years, I managed slugs through a combination of evening hand-picking and strategic beer traps. I placed shallow containers filled with beer at ground level every eight to ten feet throughout affected beds, refreshing the beer every three to four days. This trapped hundreds of slugs weekly during peak spring activity. I also went out with a flashlight one hour after sunset, which is prime slug feeding time, and hand-picked every slug I could find. This sounds tedious, but in a 200 square foot bed, I could collect fifty to eighty slugs in fifteen minutes during bad weeks. Dropping them into soapy water killed them quickly.

The real solution developed naturally as predator populations increased. By the end of my second season, I had robust ground beetle populations living in the mulch. These beetles consume slug eggs voraciously, preventing population explosions before they start. I also stopped removing every piece of dead wood and debris from around my garden, instead creating small brush piles near beds that attracted toads and provided salamander habitat. Within three years, slug damage became minimal without any intervention on my part. I still see slugs, but I also see the predators that keep them in check. The increased biodiversity of no-dig systems creates this natural balance, but you need patience and temporary management while the ecosystem establishes.

Problem Three: Bed Surface Sinking and Settling

Why New Beds Drop Several Inches

Fresh compost and new cardboard layers compress significantly as they decompose and settle. I’ve seen new beds drop four to five inches in their first year, which creates uneven surfaces, exposes cardboard edges, and sometimes leaves plants sitting in depressions where water pools. This settling is normal and inevitable, but it catches new no-dig gardeners by surprise, especially if they’ve carefully leveled beds initially. The compression happens faster in beds made with lighter, fluffier compost and slower in beds using dense, well-aged material. Weather affects the rate too; wet seasons accelerate decomposition and settling while dry conditions slow the process.

The settling creates practical problems beyond aesthetics. Plant roots can become exposed as soil drops around them. Low spots develop where water accumulates, creating soggy conditions that stress plants and promote disease. Pathways that were initially lower than bed surfaces can end up level with or higher than beds after settling, eliminating the visual definition between growing areas and walking areas. I’ve also found that significant settling can create slight slopes in beds that were initially level, causing uneven water distribution when irrigating.

Preventing Problems Through Proper Initial Depth

I now build new beds with the expectation of settling. Instead of four inches of compost, I start with six to eight inches, knowing this will compress to four to five inches by season end. I also use a mixture of compost textures when possible, combining some dense, well-aged material with lighter, fresher compost. This blend settles more uniformly than pure fluffy compost. If I’m establishing beds in fall for spring planting, I actually prefer this timing because settling happens over winter when beds are empty, eliminating the need to work around growing plants while adding supplemental compost.

When settling creates problems in established beds, I address it immediately with targeted compost additions. If a plant develops an exposed root crown, I add compost around the base, mounding it slightly to ensure good coverage even after this new material settles. For low spots where water pools, I fill them completely, adding an extra inch above the surrounding surface to account for future settling. I check beds after every heavy rain during the first year, looking for pooling water or exposed areas that need attention. This proactive approach prevents small settling issues from becoming significant problems that stress plants or create hospitable conditions for disease.

Problem Four: Nitrogen Deficiency From Decomposing Materials

The Hidden Nitrogen Tie-Up Problem

When I added wood chips as a supplemental mulch layer to some of my no-dig beds, I didn’t realize I was creating a nitrogen deficiency problem. The microorganisms breaking down high-carbon materials like wood chips and partially decomposed compost consume nitrogen in the process, temporarily making it unavailable to plants. I noticed the issue when tomatoes in my chip-mulched beds showed yellowing lower leaves and slow growth compared to beds with pure compost top-dressing. Soil tests confirmed nitrogen levels had dropped significantly despite the fact that I’d added what I thought was plenty of organic matter.

This nitrogen tie-up is temporary, eventually reversing as materials finish decomposing and microorganisms die, releasing the nitrogen they’d consumed. But “temporary” in gardening terms can mean an entire growing season, which is disastrous if you’re trying to grow nitrogen-hungry crops like corn, tomatoes, or brassicas. The problem is more severe when using high-carbon mulches like wood chips, straw, or sawdust directly on the soil surface. It’s less problematic with well-finished compost, but even compost that looks ready can tie up some nitrogen if it’s not fully stabilized.

Solutions for Maintaining Adequate Nitrogen

I solved the immediate problem by side-dressing affected plants with blood meal, applying approximately one cup per ten feet of row and watering it in thoroughly. This provided quick nitrogen that plants could access while the mulch continued decomposing. For long-term prevention, I now apply a thin layer of nitrogen-rich material before adding carbon-heavy mulches. I’ll spread a half-inch layer of alfalfa meal, soybean meal, or well-aged manure, then top this with wood chips or straw. The nitrogen-rich layer feeds decomposition without creating deficiency.

I’ve also become more selective about mulch materials. For vegetable beds where I want maximum nutrition available to plants, I stick with finished compost for top-dressing and avoid wood chips entirely except in pathways. For perennial beds and around shrubs where immediate nutrition is less critical, wood chips work beautifully and the nitrogen tie-up resolves without impacting plant performance. When I do use partially finished compost or add materials that might tie up nitrogen, I monitor plants closely during the first six weeks after application, watching for yellowing leaves or slow growth that indicates nitrogen deficiency needing correction.

Problem Five: Poor Drainage and Waterlogged Conditions

When No-Dig Beds Hold Too Much Water

While no-dig beds generally improve drainage over time, I’ve encountered situations where water retention became excessive, particularly in my clay-soil beds during wet springs. The thick compost layer acts like a sponge, absorbing and holding moisture that would normally drain through tilled soil. Combined with the cardboard layer below creating a temporary barrier to downward water movement, this can leave plant roots sitting in saturated conditions for days after heavy rain. I lost several tomato plants to root rot in my first season before I understood what was happening.

The problem is worst in beds established over compacted clay or in low-lying areas with naturally poor drainage. It’s also more severe in beds where the cardboard hasn’t yet broken down fully. During the first six to eight months, the cardboard layer acts as a partial barrier, slowing water movement into the subsoil below. This isn’t a problem in well-drained sites or during normal weather, but in heavy clay during wet periods, it creates waterlogging that stresses or kills plants intolerant of wet feet.

Improving Drainage Without Abandoning No-Dig Methods

For beds with persistent drainage problems, I’ve found that incorporating perlite or coarse sand into the top four inches of compost helps significantly. I spread a one-inch layer of perlite or builder’s sand over the bed surface and mix it into the existing compost using a garden fork. This creates air pockets and drainage channels without requiring traditional soil turning. The mixing only affects the top layer where plant roots primarily grow, leaving deeper soil structure undisturbed while improving conditions in the critical root zone.

In severe cases, I’ve built up bed height by adding additional compost until the growing surface sits four to six inches above the surrounding grade. This creates a raised bed effect while maintaining no-dig principles. The additional height ensures water drains laterally off the bed surface rather than pooling. I’ve also learned to poke vertical drainage holes through cardboard in very wet sites before adding compost, using a digging fork to create channels every twelve to fifteen inches. These holes allow water to drain through the cardboard layer immediately rather than waiting for the cardboard to decompose naturally, preventing waterlogging during that critical first season.

Problem Six: Compaction Along Bed Edges and High-Traffic Areas

How Foot Traffic Damages No-Dig Structure

Even though I know better, I sometimes step on bed edges when reaching for weeds or harvesting from the back of beds. Over time, this traffic compacts the fluffy compost layer into dense, hard material where plant roots struggle to penetrate. The compaction is most visible along bed edges where I lean or step while working, creating a one to two foot strip of compressed soil around the bed perimeter. Plants growing in these compacted zones show noticeably slower growth and smaller size compared to plants in the bed center where soil remains light and fluffy.

The problem develops gradually, making it easy to ignore until damage is significant. Unlike tilled beds where compaction appears as hard, cracked soil, no-dig compaction often looks normal on the surface. The compost still appears loose and dark, but squeeze a handful and you’ll feel the difference immediately. Healthy no-dig soil crumbles apart easily. Compacted areas form a dense clump that holds together even when you try to break it apart. This compaction reduces air pore space that roots need for healthy growth and limits water infiltration, creating the exact problems no-dig methods are designed to prevent.

Prevention Through Smart Bed Design and Repair Techniques

I now design all beds at four feet wide maximum, which allows me to reach the center easily from either side without stepping on growing areas. For beds wider than four feet, I install permanent stepping stones or wood planks at strategic intervals, creating access points that distribute my weight across a hard surface rather than compacting soil. These internal paths let me reach the bed center for planting, weeding, and harvest without ever stepping directly on compost.

Where compaction has already occurred, I repair it without abandoning no-dig principles. I gently insert a digging fork into the compacted area and rock it back and forth, creating fissures and air channels without lifting or turning soil. I work in a grid pattern, inserting the fork every six to eight inches throughout the compacted zone. After loosening, I add a two to three inch layer of fresh compost over the area, which works down into the fissures and further improves structure. This restoration process takes twenty to thirty minutes for a typical compacted bed edge but makes a dramatic difference in plant performance within weeks.

Problem Seven: Disease Pressure From Constant Moisture and Organic Matter

Why Some Diseases Thrive in No-Dig Beds

The consistently moist surface layer in no-dig beds can promote fungal diseases like damping off, botrytis, and various stem rots, particularly in cool, humid conditions. I lost an entire planting of basil seedlings to damping off one cool May when consistent rain kept the soil surface wet for ten consecutive days. The pathogen spread through the moist compost layer, toppling seedlings one after another despite perfect care otherwise. The same conditions in a traditional tilled bed with exposed, quick-drying soil surface would have caused far less damage.

The problem is most severe with direct-seeded crops and young transplants that sit close to the constantly moist mulch layer. Mature plants with stems elevated above the surface experience fewer issues. I’ve noticed that crops like lettuce, which grow as rosettes close to the soil, show more disease problems than crops like tomatoes with significant stem height. The disease pressure also varies by season, with cool, wet spring weather creating far more problems than hot, dry summer conditions when the soil surface dries quickly between waterings.

Cultural Practices That Reduce Disease Risk

I’ve learned to pull compost back slightly from plant stems, creating a two to three inch diameter circle of exposed soil around each plant. This small modification allows air circulation around the stem base and lets the area dry between waterings, dramatically reducing stem rot and damping off problems. For direct seeding, I’ve started using a very fine, screened compost for the top half-inch of the seedbed. This fine texture doesn’t stay as wet as chunky compost, and it still provides excellent seed-to-soil contact for germination while reducing disease risk.

I also pay much more attention to plant spacing than I did in traditional beds. The urge to maximize production by planting densely is strong, but in no-dig beds with their moisture-retentive mulch layer, tight spacing creates a humidity-trapped environment where fungal diseases explode. I now space plants ten to twenty percent wider than traditional recommendations, which improves air circulation, allows foliage to dry quickly after rain or irrigation, and has actually increased total yield despite fewer plants per bed because each plant grows larger and healthier with better disease resistance.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: How long before no-dig beds stop having slug problems?

A: Most beds reach natural slug balance by the end of the second growing season as predator populations establish, though you’ll need active management with traps and hand-picking during the first two years.

Q: Can I fix a poorly made no-dig bed or do I need to start over?

A: Most problems are fixable without starting over; add more cardboard and compost over problem areas, address compaction with a fork, and supplement nitrogen if plants show deficiency symptoms.

Q: Why are my plants yellowing in no-dig beds when they look healthy in tilled beds?

A: This usually indicates nitrogen tie-up from decomposing organic matter; side-dress with blood meal or fish emulsion and avoid using high-carbon mulches like wood chips in active growing areas.

Q: How much settling should I expect in the first year of a no-dig bed?

A: Expect three to five inches of settling in the first year depending on compost density and moisture levels, which is why starting with six to eight inches of initial depth prevents exposure problems.

— Grandma Maggie