I’ll never forget the winter I walked out to my front porch and saw nothing but empty, sad-looking pots stacked against the house. For years, I treated container gardening like a warm-weather hobby, filling my planters with petunias in May and dumping them in October. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realize those containers could be working for me year-round, even here where January temperatures regularly dip below zero. After more than two decades of experimenting with four-season containers in Zones 4 and 5, I’ve learned that a cold climate doesn’t mean your porch or patio has to look lifeless for six months of the year. It means you plan differently, choose smarter, and learn a few tricks that make all the difference. Let me walk you through everything I know about building containers that look beautiful even when the snow is flying.

Why Four-Season Containers Work Even in the Coldest Zones

The whole idea behind a four-season container is beautifully simple: you anchor your planter with one tough, permanent shrub or small evergreen that stays put all year long, then swap out the supporting cast of smaller plants as the seasons change. That central plant is your “thriller,” the backbone that gives your container structure whether it’s draped in summer flowers or dusted with December snow. The key insight that changed everything for me is understanding that container roots are far more exposed to cold than roots in the ground. In a garden bed, the surrounding soil acts as a massive insulator, keeping root temperatures relatively stable. In a container, only a thin wall of pot material separates those roots from frigid air. That’s why the standard advice from university extension programs is to choose a centerpiece plant rated one to two hardiness zones colder than where you live. If you garden in Zone 5, for example, you want a shrub rated for Zone 3 or Zone 4 at the coldest. Follow that rule, and you’ll be amazed at what survives.

Choosing Your Anchor Plant: The Evergreen Backbone

This is the single most important decision you’ll make, because your anchor plant is the one thing that stays in that container through blizzards, ice storms, and those awful late-March freezes that make you question why you garden at all. After years of trial and error, I’ve found a handful of evergreens that consistently pull their weight in cold-climate containers.

Dwarf Alberta Spruce is my go-to recommendation for beginners. It’s hardy to Zone 2, grows in a tidy little cone shape that looks like a miniature Christmas tree, and rarely exceeds 4 to 6 feet even after a decade. I’ve had one in a large stone planter on my front steps for eleven years now, and it still brings me joy every single morning.

Emerald Petite Arborvitae is another wonderful choice, hardy to Zone 3 and naturally compact, which means less pruning. It has that lovely soft, feathery texture that catches the light beautifully. For something a little more dramatic, Blue Arrow Juniper grows in a narrow columnar form that adds real architectural presence, and it’s hardy to Zone 4. I’ve also had excellent luck with various Chamaecyparis cultivars in Zones 4 through 8, especially the gold-tipped varieties that practically glow in winter sunlight. One option I absolutely love, though it requires a bit more commitment, is Red Sprite Winterberry. Those brilliant red berries against bare branches in winter are stunning. The catch is that winterberry needs both a male and a female plant to produce berries, so you’d need two containers or a male planted nearby in the ground. I’ve done both, and I promise the extra effort is worth it when those berries light up a gray February day.

Building Your Container for Cold-Climate Success

The Right Pot Makes or Breaks Your Plan

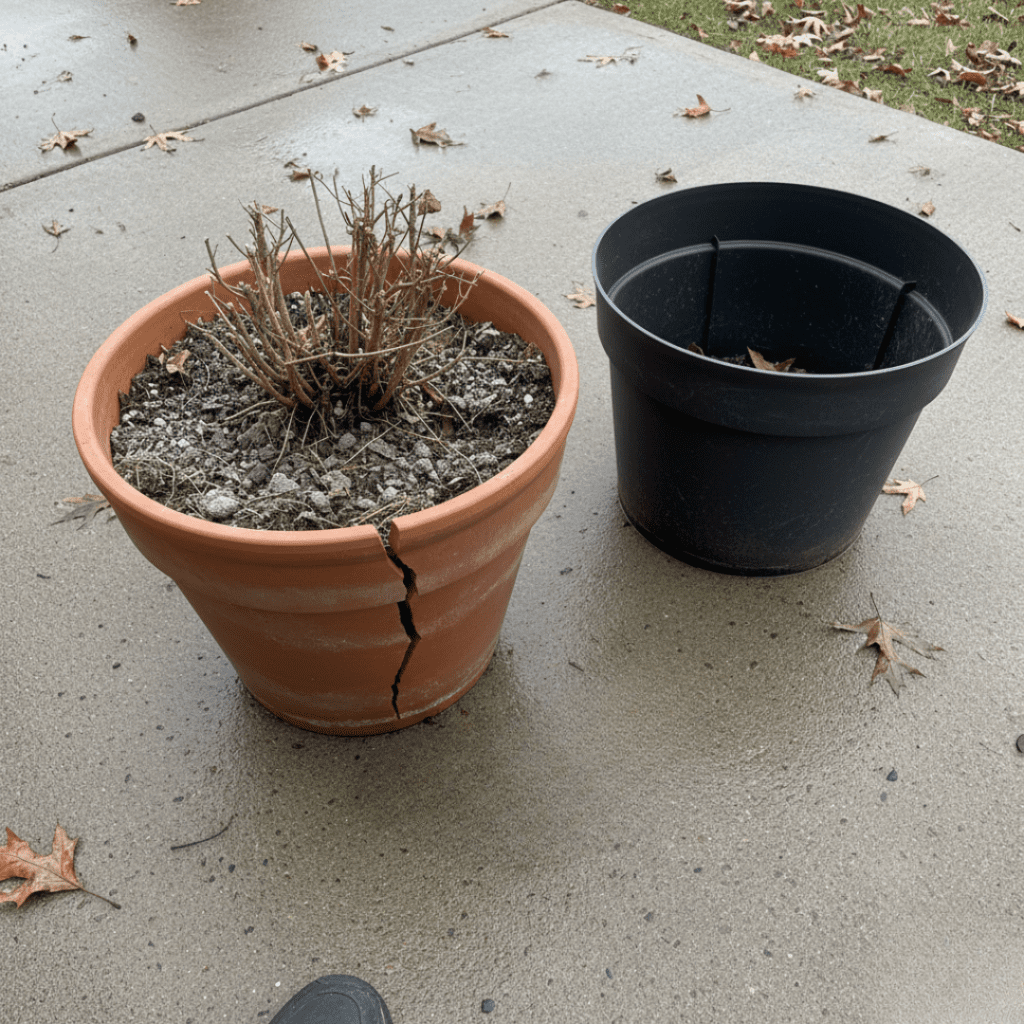

I learned this lesson the hard way when I lost a gorgeous terra-cotta pot—and the arborvitae inside it—during a particularly brutal January. Clay and terra-cotta expand and contract with freeze-thaw cycles, and in cold climates, that means cracking and shattering. After that heartbreak, I switched to materials that can handle the stress: fiberglass, thick-walled resin, heavy-duty plastic, natural stone, and sturdy wood like cedar or redwood. Fiberglass is my personal favorite because it’s lightweight enough that I can still rearrange my porch without help, but tough enough to flex with temperature swings without cracking. Stone planters are gorgeous and nearly indestructible, though they’re heavy enough that once you place one, it’s staying put for good.

Size matters enormously in cold-climate container gardening. Think big—at least 18 to 24 inches across and 15 gallons or more. The greater the volume of soil surrounding your plant’s roots, the more insulation those roots have against the cold. A small 3-gallon pot will freeze solid in hours during a cold snap, but a 20-gallon planter holds enough thermal mass to buffer temperatures significantly. You also need room around your anchor shrub to tuck in seasonal plants throughout the year. Every container must have drainage holes. I cannot stress this enough. Standing water that freezes inside a pot will crack even the toughest material, and waterlogged roots rot faster than they freeze. I drill extra holes in the bottom of any pot that seems undersized in the drainage department, and I always elevate my containers an inch or two off the ground on pot feet or small wooden blocks to keep water flowing freely.

Seasonal Swaps: Spring Through Fall

Here’s where four-season containers become truly exciting. Your anchor evergreen provides the permanent structure, and everything else gets swapped in and out like changing accessories on a favorite outfit. In spring, I start with the hardiest fillers first, because cold-climate springs are unreliable at best. Pansies, hellebores, and pulmonaria can handle the late frosts that inevitably arrive after you thought winter was over. I usually plant these around mid-April in my Zone 5 garden, choosing well-established plants from the nursery rather than tiny starts, since the growing season hasn’t kicked into gear yet. By late May or early June, once nighttime temperatures stay reliably above 50 degrees, I pull those spring players and swap in the summer show. This is where you can really have fun—trailing scaevola or sweet alyssum spilling over the edges, upright salvias or lantana adding color in the middle, or even a dramatic tropical like a small hibiscus for a sunny spot. I’ve been known to tuck a compact tomato into a large container alongside my spruce, and honestly, it looks charming and produces a surprising amount of fruit.

When fall arrives, I transition again, usually in mid-September. I pull the summer annuals, refresh the potting mix with a handful of compost, and tuck in hardy perennials from my own garden beds—hostas, heuchera, ornamental grasses, and small ferns all work beautifully. I add ornamental kale and mums for color, and I’m not ashamed to say I scatter in a few small pumpkins and gourds just for fun. The key with fall planting is to use established, mature plants since root growth slows dramatically as temperatures drop. A tiny transplant won’t have time to settle in before the ground starts to harden, but a division from a well-rooted perennial will hold its own just fine.

Getting Through Winter: Protection That Actually Works

Winter is the real test, and this is where so many gardeners give up. Don’t. Before the potting soil freezes solid, I remove the fall plants, top up the soil around my anchor evergreen, and add a thick layer of mulch—4 to 6 inches of straw, shredded bark, or pine needles right over the surface. This layer locks in ground heat and prevents the rapid temperature swings that do the most damage. Then I look at my pot itself. If I’m using a lighter-weight container, I wrap the sides with bubble wrap or burlap, focusing on the base and sides where cold hits hardest. I leave the top open for air circulation and the occasional winter watering.

Placement is everything in winter. I cluster my containers together against a south-facing wall, which creates a small microclimate where the pots share warmth and the building blocks wind. The collected thermal mass of several large containers grouped together holds soil temperature far steadier than any single isolated pot can manage. I put the most cold-sensitive containers in the center and ring them with the toughest ones. On the very coldest nights, when forecasts dip to minus 20 or below, I’ll drape a frost blanket over the whole cluster. It’s not glamorous, but it works. And here’s something many people don’t realize: you still need to water in winter. About once a month during dry spells, I check soil moisture by poking my finger down a couple of inches. Moist soil actually insulates roots better than dry soil, and water in the soil releases a small amount of heat as it freezes, forming a protective ice layer around the roots.

Making Winter Containers Beautiful, Not Just Surviving

Winter Decorating and the January Test

I have a personal rule I call the January Test: if my front porch containers look good on the grayest, coldest day of January, I’ve done my job. Once the fall plants come out, I don’t just leave a bare evergreen standing in mulch. I add cut greenery—cedar boughs, pine branches, and red-twig dogwood stems are my staples. The red stems of dogwood against green evergreen foliage and white snow is a combination that never gets old. I tuck in preserved berries, pine cones, and sometimes birch branches for height and texture. A friend of mine strings small battery-operated lights on her container spruce every year, and I’ll admit I’ve stolen that idea entirely. After the holidays, you can pull out any festive additions and leave the natural greenery, which stays attractive well into March. Some years I’ve decorated my blueberry bush containers with nothing but a string of lights, and the bare branching structure becomes a kind of winter sculpture that I find surprisingly beautiful.

The beauty of a four-season container is that it teaches you to see your garden differently. Instead of viewing winter as a six-month gap between gardening seasons, you start to notice the architecture of bare branches, the texture of evergreen needles holding snow, the way morning light catches frost on a juniper’s blue-green foliage. After fifty years of gardening, I still walk out to my porch every winter morning and feel something like wonder. That’s what a well-planned container can give you, even on the coldest day of the year. Start with one container, one tough little evergreen, and the willingness to experiment. I promise you’ll be hooked before the first snowflake falls.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I use regular garden soil in my four-season containers?

A: No—always use a high-quality potting mix designed for containers, because garden soil compacts too heavily, drains poorly, and can crack pots when it freezes and expands. I mix in about 20 percent perlite for extra drainage in my winter containers.

Q: How often should I water container plants in winter?

A: Check soil moisture about once a month during dry spells by poking your finger 2 inches into the soil. If it’s dry, give it a good drink on a day when temperatures are above freezing—moist soil actually insulates roots better than dry soil.

Q: Do I need to fertilize my anchor evergreen during winter?

A: Absolutely not. Fertilizing in winter encourages tender new growth that will be killed by cold. Save your feeding for early spring when you start to see signs of new growth, and use a slow-release granular fertilizer at half strength.

Q: What if my container evergreen looks brown or dried out after a hard winter?

A: Don’t panic or pull it out—winter burn from drying winds is common and often recoverable. Water it well once the soil thaws, scratch a small branch with your fingernail to check for green underneath, and give it until mid-May before making any decisions. I’ve seen plenty of “dead” evergreens push fresh growth in spring.

— Grandma Maggie