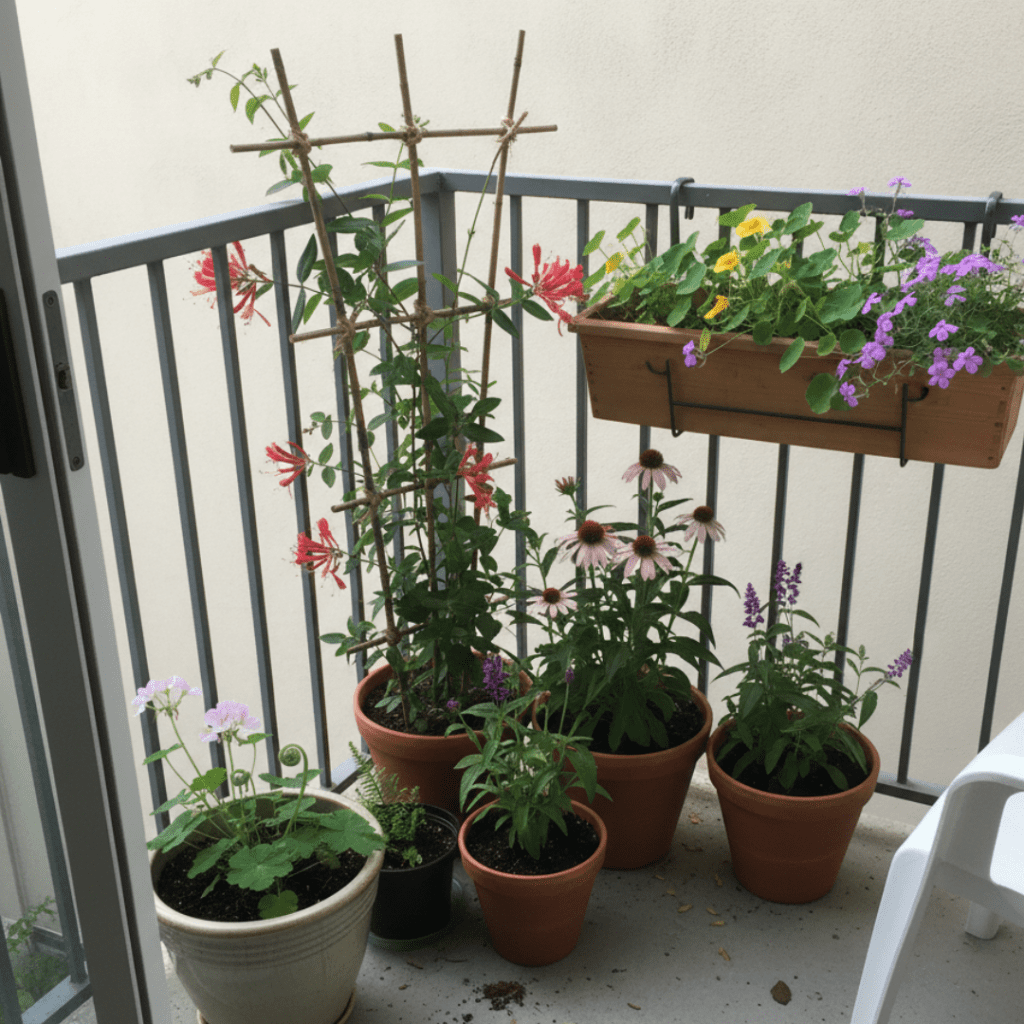

After fifty years of tending gardens, I can tell you that the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done wasn’t building my raised beds or planting my first fruit tree. It was watching a monarch butterfly land on a pot of milkweed sitting on my daughter’s third-floor apartment balcony. She had called me in tears, convinced that living in a city meant she could never have a real garden. Well, I showed her otherwise, and now I want to show you. You don’t need a sprawling backyard to create meaningful habitat for pollinators. Bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds will happily find your balcony if you give them a reason to visit. A few well-chosen native plants in the right containers can turn even the smallest outdoor space into a thriving pollinator waystation. Let me walk you through exactly how to make it happen.

Why Native Plants Make All the Difference

I spent years watching gardeners fill their balcony pots with petunias and geraniums—beautiful flowers, sure, but of very little use to the bees and butterflies that actually need our help. Native plants are different because they evolved alongside local pollinators over thousands of years. That means native blooms offer the right nectar, the right pollen shape, and the right timing for the insects in your region. A non-native marigold might look lovely in a window box, but a pot of native black-eyed Susans will feed specialist bees that simply cannot survive on anything else. I’ve also found that native plants tend to be tougher in containers than people expect. Because they’re adapted to your local climate, they handle temperature swings and irregular watering far better than most ornamental annuals. After my daughter switched from store-bought impatiens to native coneflowers and wild bergamot on her balcony, she went from zero pollinator visits to counting bumble bees every single morning within about three weeks.

Choosing the Right Containers and Soil

Bigger Pots, Happier Roots

Here’s something I learned the hard way: native plants generally have deeper root systems than the commercial annuals most of us are used to growing in pots. That means you need to think bigger when choosing containers. I recommend pots that are at least 12 to 14 inches deep and 12 inches wide as a starting point, and for plants like milkweed or coneflowers, a 3- to 5-gallon container is even better. The size of your pot directly affects how large and how healthy your plant can grow. I once grew two identical purple coneflower seedlings side by side—one in a small 4-inch starter pot and one in a 3-gallon container. By midsummer, the plant in the larger pot was three times the size and blooming profusely while the smaller one barely managed a single flower.

As for materials, you have plenty of options. Lightweight fiberglass and recycled plastic work wonderfully on balconies because they’re easy to move and won’t crack in winter. Terracotta is beautiful and breathes well, but it dries out faster in summer heat and can shatter in freezing temperatures. If weight is a concern on your balcony, stay away from concrete or stone. Whatever you choose, drainage holes are absolutely non-negotiable. Native plants, especially prairie species, will rot and die in waterlogged soil faster than almost anything else you could grow. I always set a saucer underneath to catch runoff, partly to protect the downstairs neighbors and partly because that saucer allows the potting mix to wick moisture back up through capillary action—a trick that keeps the soil more evenly moist.

The Right Soil Mix Makes Everything Easier

Never, and I mean never, fill your balcony containers with garden soil dug from the yard. It compacts terribly in pots and holds too much water. I use a simple blend of one part high-quality potting mix, one part perlite, and one part compost. This gives you good drainage, decent water retention, and enough organic matter to get plants established. Here’s something that surprises a lot of people: most native plants actually prefer lean soil. They evolved on prairies and in meadows where the ground wasn’t particularly rich. If you dump a bunch of heavy fertilizer into your containers, you’ll end up with a lot of floppy, green growth and very few flowers. I fertilize my native containers lightly with a balanced slow-release formula once in spring, and that’s it. The compost in my soil mix provides everything else these tough plants need for the rest of the season.

The Best Native Plants for a Balcony Pollinator Garden

Purple Coneflower: The Backbone of Any Container Pollinator Garden

If I could only grow one native plant on a balcony, it would be purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) without a moment’s hesitation. This plant is incredibly hardy across zones 3 through 9, which means it can overwinter in a large container in most of the country. The key is choosing a pot with enough volume—at least 3 gallons—to insulate those roots from temperature extremes. I’ve overwintered coneflowers on my daughter’s Chicago balcony for three consecutive years by simply pushing the pots against the building wall and mounding 3 to 4 inches of shredded leaf mulch on top of the soil. The blooms start in early summer and keep going right through the first frost if you deadhead spent flowers, providing months of steady nectar for bees, butterflies, and even hummingbirds. Leave the seed heads standing through winter and you’ll attract goldfinches, too. For container growing, I love the dwarf cultivar ‘Kim’s Knee High,’ which stays compact at about 18 to 24 inches—perfect for a balcony where tall plants might topple in the wind.

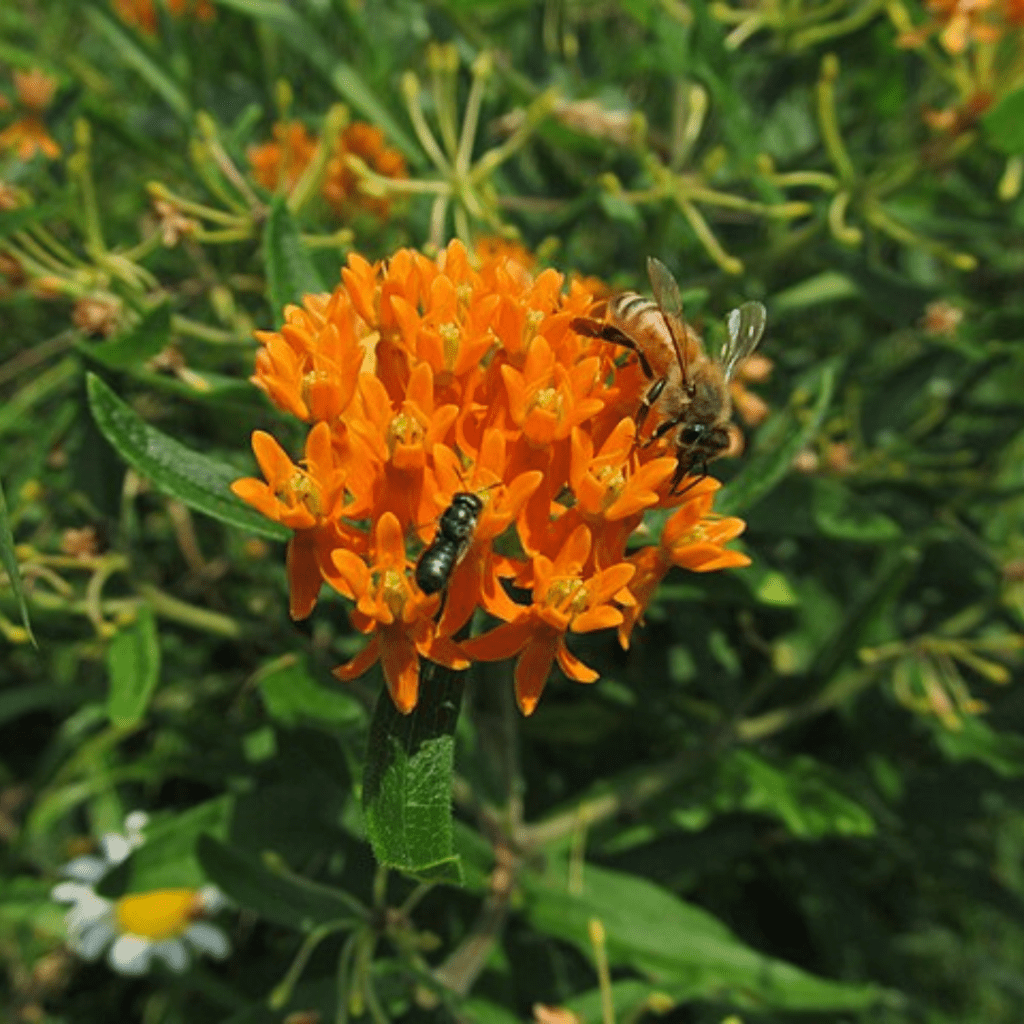

Butterfly Weed: A Monarch Magnet That Thrives in Pots

Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) is one of the best milkweed species for container growing, and it’s absolutely essential if you want monarchs visiting your balcony. Unlike common milkweed, which spreads aggressively by underground runners, butterfly weed stays compact and doesn’t form rhizomes, making it perfectly behaved in a pot. Its blazing orange flowers are stunning against a railing, and monarch females will lay their tiny eggs right on the leaves. I recommend a container at least 14 inches deep because this species does develop a meaningful taproot, though it’s nowhere near as deep-reaching as common milkweed. Use a well-draining potting mix and water when the top inch of soil feels dry. One important note: avoid tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) even though it’s widely sold at garden centers. It can disrupt monarch migration patterns by encouraging butterflies to linger too long in areas where they shouldn’t overwinter. Stick with native species—your monarchs will thank you.

Filling Out the Garden: More Container-Friendly Natives

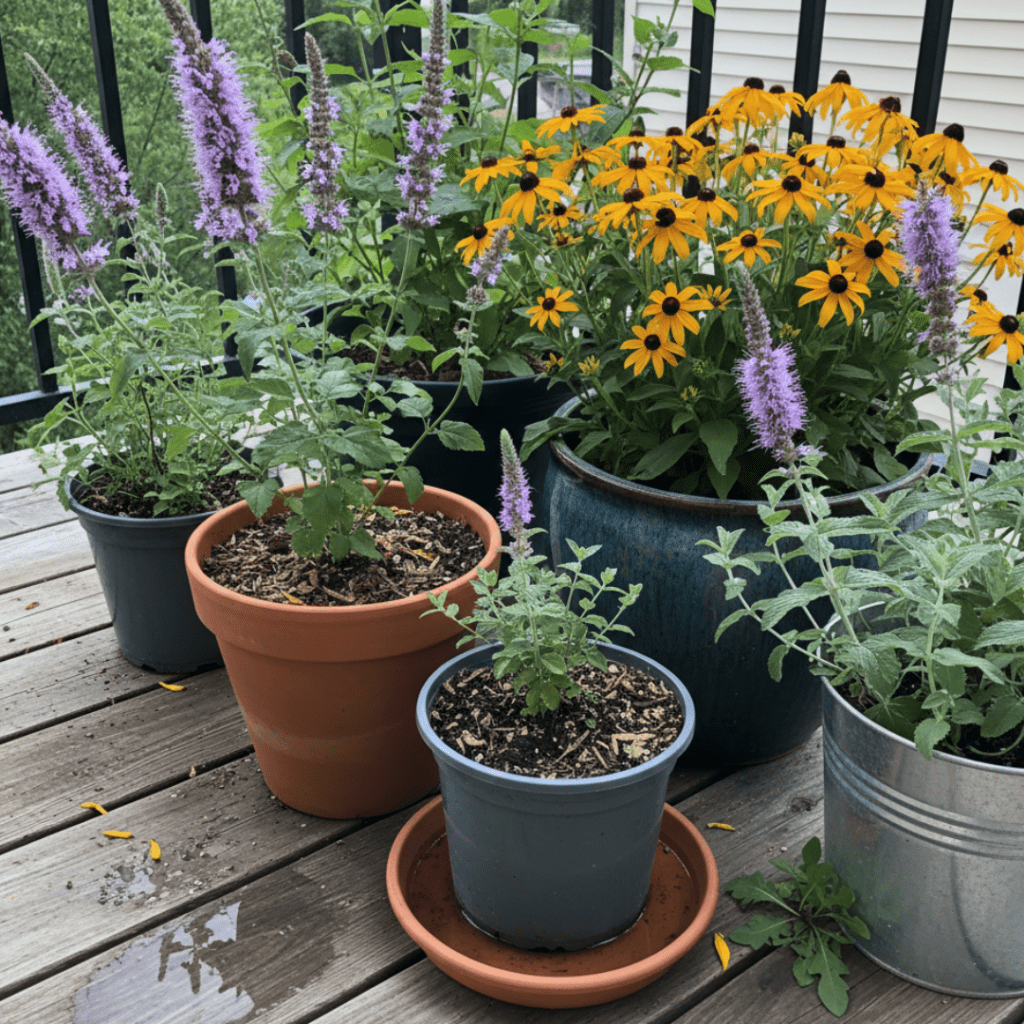

A truly effective pollinator garden needs blooms spread across the entire growing season, not just a burst of color in July. I’ve learned to think of my container garden in three waves: early, mid, and late season. For spring, wild geranium (Geranium maculatum) and golden Alexanders (Zizia aurea) provide some of the first nectar sources when early-emerging bees are desperately hungry. For midsummer, your coneflowers and butterfly weed take center stage, joined by anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), which is an absolute bee magnet with tall lavender flower spikes that bloom for weeks. For late summer and fall, blazing star (Liatris spicata) sends up dramatic purple spires that monarch butterflies adore during their southward migration, while black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia hirta) keep pumping out cheerful golden blooms until frost. One of my favorite discoveries has been mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium), which attracts more different pollinator species than almost anything else I’ve ever grown. I once counted seven different types of bees, two species of wasps, and a dozen tiny pollinator flies all on one mountain mint plant in a single afternoon.

Designing Your Balcony for Maximum Impact

Space on a balcony is precious, so you need to think both horizontally and vertically. I tell every new balcony gardener to start by mapping their sunlight. Spend a day watching where the sun hits and for how long. Most native pollinator plants need six to eight hours of direct sun, so your sunniest spot gets your most important containers. If your balcony is partially shaded, don’t despair—wild bleeding heart, wild geranium, and native ferns can provide cover and greenery in the dimmer corners while your sun-lovers do the heavy pollinator lifting at the railing.

Think vertically by training a native coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) vine up a small trellis or along your railing. It produces tubular red flowers that hummingbirds absolutely cannot resist, and it behaves well in a 5-gallon container. Window boxes along the railing edge work beautifully for lower-growing natives like moss phlox or coreopsis. I like to cluster my containers in groups of three to five rather than spacing them out individually—pollinators are more likely to find a concentrated patch of blooms than a single lonely pot in the corner. Place your milkweed and most fragrant plants right at the railing’s edge where butterflies can access them easily during flight.

Watering, Feeding, and Overwintering Your Container Natives

Containers dry out much faster than in-ground gardens, and this is the single biggest adjustment you’ll make as a balcony gardener. Even drought-tolerant natives like coneflower and butterfly weed need regular water when their roots are confined to a pot. During hot summer weeks, I check my containers every single day, sometimes twice. The finger test works perfectly: push your finger about an inch into the soil, and if it feels dry, water until it runs out the drainage holes. If you travel or tend to forget, consider self-watering containers or adding water-retaining crystals to your potting mix. I’ve also found that a 2-inch layer of mulch on top of each container—shredded bark or even small pebbles—reduces evaporation dramatically, sometimes cutting watering frequency in half.

Overwintering is where most balcony gardeners get nervous, but it’s simpler than you think. The general rule I follow is to choose plants hardy to at least two zones colder than where you live. Since container roots are more exposed to freezing than roots in the ground, a plant rated for zone 5 in a garden might only survive to zone 7 conditions in a pot. Push your containers against the building wall in late fall, where they’ll benefit from the structure’s residual heat. Mound 3 to 4 inches of shredded leaves or bark mulch over the soil surface. In really cold zones, you can wrap the pot itself in burlap or bubble wrap for extra insulation. Don’t overwater dormant plants through winter—check every couple of weeks and water lightly only if the soil is completely dry. I’ve overwintered coneflowers, blazing star, and anise hyssop on exposed balconies through harsh winters using nothing more than these techniques, and they come roaring back every spring.

Beyond Plants: Completing Your Pollinator Habitat

A truly welcoming pollinator balcony goes beyond just flowers. Pollinators need water, so I keep a shallow dish filled with pebbles and a thin layer of water on my balcony at all times. Butterflies and bees will land on the pebbles and drink from the edges—they can’t use deep water. Refresh it every day or two to prevent mosquito breeding. You can also provide nesting habitat by tucking a small bundle of hollow bamboo stems or a simple bee hotel between your containers. Native solitary bees, which are gentle and rarely sting, will lay their eggs in the hollow tubes and return season after season. I remember placing a tiny bamboo bundle on my daughter’s balcony one spring, and by August she had a dozen native mason bees nesting in it. She was so proud she called me every time one came and went.

And here’s my most important piece of advice after decades of gardening for wildlife: resist the urge to make everything tidy. Leave your seed heads standing through winter for the birds. Let a few fallen leaves sit in the containers as overwintering habitat for tiny beneficial insects. Skip the pesticides entirely—even organic ones can harm the very pollinators you’re trying to support. Your balcony doesn’t need to look like a magazine cover to be doing incredible ecological work. Every pot of native flowers on every balcony in every city adds up, and that gives me more hope for the future than just about anything else in gardening.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: How many containers do I really need to attract pollinators?

A: I’ve seen bees find as few as two or three pots of native flowers on a balcony, but I recommend starting with at least five containers holding three to four different species so you have blooms from spring through fall.

Q: My balcony only gets about four hours of sun—can I still grow a pollinator garden?

A: Four hours of direct sun is enough for shade-tolerant natives like wild geranium, wild bleeding heart, and blue wood aster, which still attract bees and butterflies, though you’ll have fewer plant choices than a full-sun balcony.

Q: Do I need to replace my native container plants every year like annuals?

A: No, most native perennials will come back year after year in containers if you choose species hardy to at least two zones colder than yours and provide basic winter protection like mulching and pushing pots against the building wall.

Q: Is it true I should avoid tropical milkweed for monarchs?

A: Yes—tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) can disrupt monarch migration patterns and harbor parasites because it doesn’t die back naturally in mild winters, so always choose a native milkweed species like butterfly weed or swamp milkweed instead.

— Grandma Maggie