I’ll never forget the winter I visited my niece’s sixth-floor apartment in Philadelphia and saw a thriving rosemary bush on her south-facing balcony—in January. Now, rosemary is reliably perennial in Zone 8, and Philadelphia sits squarely in Zone 7a. By every rule in the book, that plant should have been long gone. But there it was, green and fragrant, tucked against a warm brick wall with afternoon sun bouncing off the glass door behind it. That was the moment I truly understood what microclimates could do in a city. After more than fifty years of gardening, I’ve learned that your hardiness zone is a starting point, not a sentence. And if you garden on a balcony or rooftop in an urban area, you may have more growing power than you realize. Let me walk you through how to find it and use it.

Why Does a Balcony Act Like a Different Zone?

Most people think of hardiness zones as fixed lines on a map, and in a broad sense they are. But those zone designations are based on average annual extreme minimum temperatures recorded at weather stations—usually at airports or open fields, not nestled between buildings six stories up. A city balcony is a different animal entirely. Brick, concrete, and glass absorb heat during the day and radiate it slowly through the night, creating a warm pocket that can push your effective growing zone by a full one to two zones. A south-facing brick wall, in particular, acts like a thermal battery. I’ve measured the difference myself with a simple infrared thermometer, and on a cold December night, the air two inches from a sun-warmed brick wall can be 8 to 12 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the open air just five feet away. That’s the difference between Zone 6b and Zone 8a.

There’s also the matter of wind protection. At ground level in a suburban garden, cold wind can strip heat from plants and soil in minutes. But a balcony enclosed on two or three sides by building walls creates a sheltered pocket where cold air doesn’t settle and biting wind doesn’t reach. I’ve seen gardeners on protected urban balconies successfully overwinter fig trees, crepe myrtles, and even some camellias that would never survive in an open Zone 6 yard. The building itself becomes your greenhouse wall.

Understanding Your Balcony’s True Growing Potential

Measure Soil Temperature, Not Just Air

Here’s a mistake I see constantly, and I made it myself for years: relying on air temperature to judge what your plants can handle. Air temperature fluctuates wildly on a balcony—a gust of wind can drop it ten degrees in seconds, and a burst of reflected sunlight can spike it just as fast. What actually determines whether your perennial survives winter is the temperature of the root zone. Roots are far less cold-hardy than the above-ground portions of most plants, and in a container on a balcony, those roots are much more exposed than they would be in the ground.

I recommend picking up a soil thermometer—you can find a decent one for about eight dollars—and checking your container soil temperatures at dawn on the coldest mornings of winter. That’s your true minimum. Record it weekly from late November through February, and after one season you’ll have a reliable picture of your balcony’s real hardiness zone. In my niece’s case, her containers against the south-facing brick wall never dropped below 18 degrees Fahrenheit at the root level, even when the city’s official low hit 5 degrees. That’s a massive difference, and it’s the reason her rosemary and lavender survive year after year.

Mapping Your Balcony’s Warm and Cool Spots

Not every corner of your balcony benefits equally from the microclimate effect, and this is something I wish someone had told me decades ago. The spot right against the building wall, especially a south- or southwest-facing one, will be the warmest. Move just three feet toward the railing and you’ll find temperatures can drop significantly, particularly if the railing is open metalwork that lets wind through. I like to think of a balcony as having three zones: the warm wall zone within about 18 inches of the building, the transitional middle zone, and the exposed edge zone near the railing.

Place your zone-pushing experiments—the plants rated one or two zones warmer than your official designation—in that warm wall zone. Use the middle zone for plants within your normal range, and reserve the exposed edge for your toughest, most cold-hardy containers. If you place a soil thermometer in each zone during winter, you may be surprised to find a 10- to 15-degree difference between the wall and the railing. I’ve tested this on three different balconies over the years, and the pattern holds remarkably consistent.

Plants Worth Pushing in Zone 6 Urban Balconies

Now for the fun part—what can you actually grow? If your balcony microclimate effectively gives you Zone 7b or 8a conditions at the root level, the list opens up beautifully. I’ve had personal success or seen reliable results with several plants that have no business surviving a Zone 6 winter in the open ground.

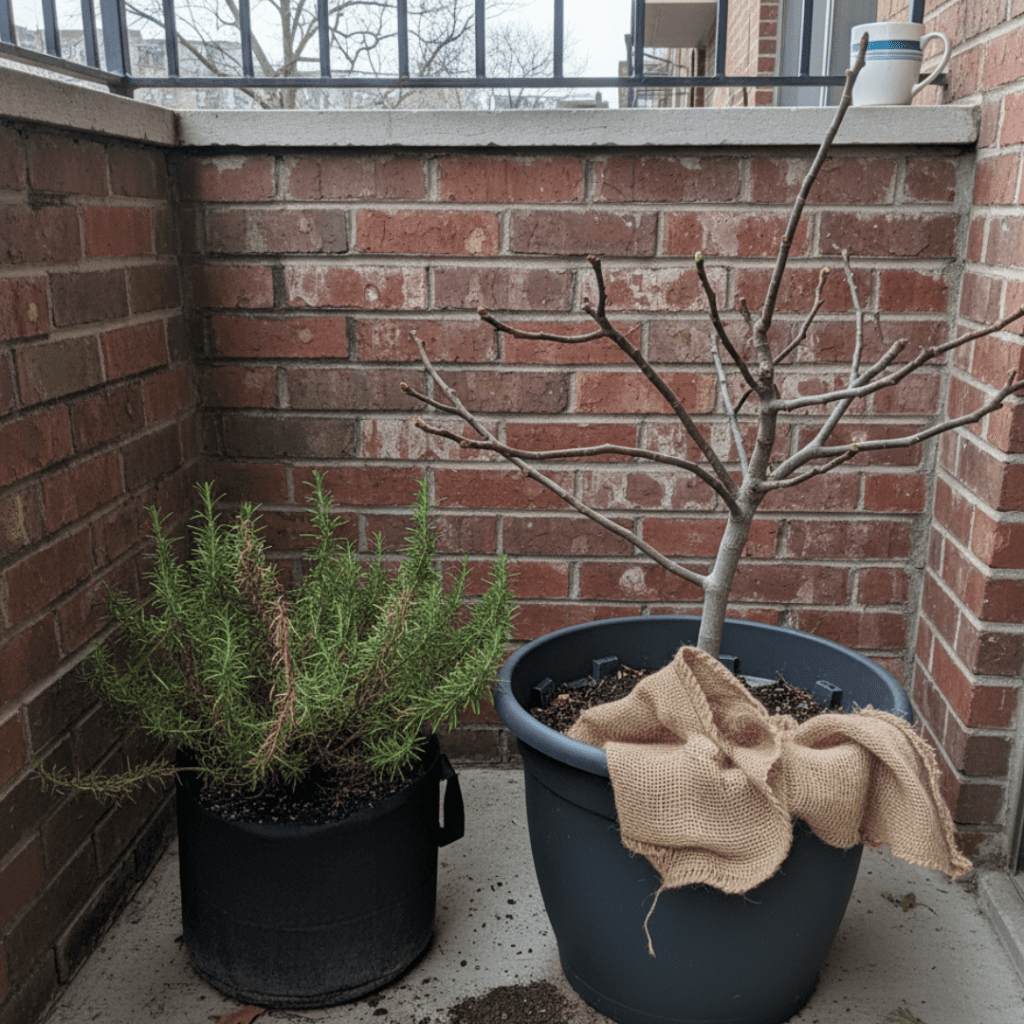

Chicago Hardy fig is my top recommendation for zone-pushing beginners. It’s rated for Zone 6 in the ground, but in a container it typically needs Zone 7 protection. Against a warm wall, I’ve watched it thrive for five consecutive winters on a Philadelphia balcony with nothing more than a layer of burlap wrap in January.

Rosemary, particularly the ‘Arp’ and ‘Hill Hardy’ cultivars, is another excellent candidate. These are rated Zone 7, and with the wall-zone advantage, they come through Zone 6 winters reliably.

Crepe myrtle in a large container—at least 20 inches across—can work beautifully in a warm balcony pocket. The ‘Acoma’ and ‘Natchez’ varieties are among the hardiest, rated to Zone 7a, and they reward you with months of summer bloom.

I’ve also seen success with Southern sword fern, gardenia ‘Kleim’s Hardy’, and even some tea olive (Osmanthus) varieties. The key is choosing plants rated just one to two zones above yours—not three or four. Pushing from Zone 6 to Zone 8 territory is achievable. Trying to grow Zone 10 tropicals through a Zone 6 winter, even on the warmest balcony, is a recipe for heartbreak.

Protecting Your Investment Through Winter

Container Insulation That Actually Works

Even with a favorable microclimate, containers are vulnerable in ways that ground-planted roots are not. The soil in a pot freezes from all sides—top, bottom, and every edge—while soil in the ground benefits from the earth’s thermal mass below. After thirty years of experimenting, I’ve found that wrapping containers with bubble wrap insulation, the kind with a foil backing, makes a remarkable difference. Wrap the pot itself, not the plant, in two layers and secure it with packing tape. This simple step can raise root-zone temperatures by 5 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit on the coldest nights.

For your most tender zone-pushers, grouping containers together creates additional protection. I call it the huddle method—pots pushed close together share thermal mass and shelter each other from wind. Place your most vulnerable plant in the center of the group, closest to the wall, with hardier pots forming a buffer on the outer edges. During extended cold snaps below 15 degrees Fahrenheit, draping a frost cloth or even an old bedsheet over the entire cluster and tucking it around the pots adds another few degrees of safety. I remember one February night in 2015 when the forecast called for minus-2 degrees in the city. My niece huddled her pots, wrapped them, and draped a double layer of frost cloth. Every plant survived. Preparation makes all the difference.

The Watering Mistake Most Balcony Gardeners Make in Winter

This catches people off guard every single year: winter desiccation kills more container perennials than cold does. When the soil in your pot freezes solid, the roots can’t take up water, but the leaves—especially on evergreens like rosemary and gardenia—continue losing moisture to dry winter wind. The plant essentially dies of thirst while surrounded by ice. I’ve lost more plants to this than I care to admit before I understood what was happening.

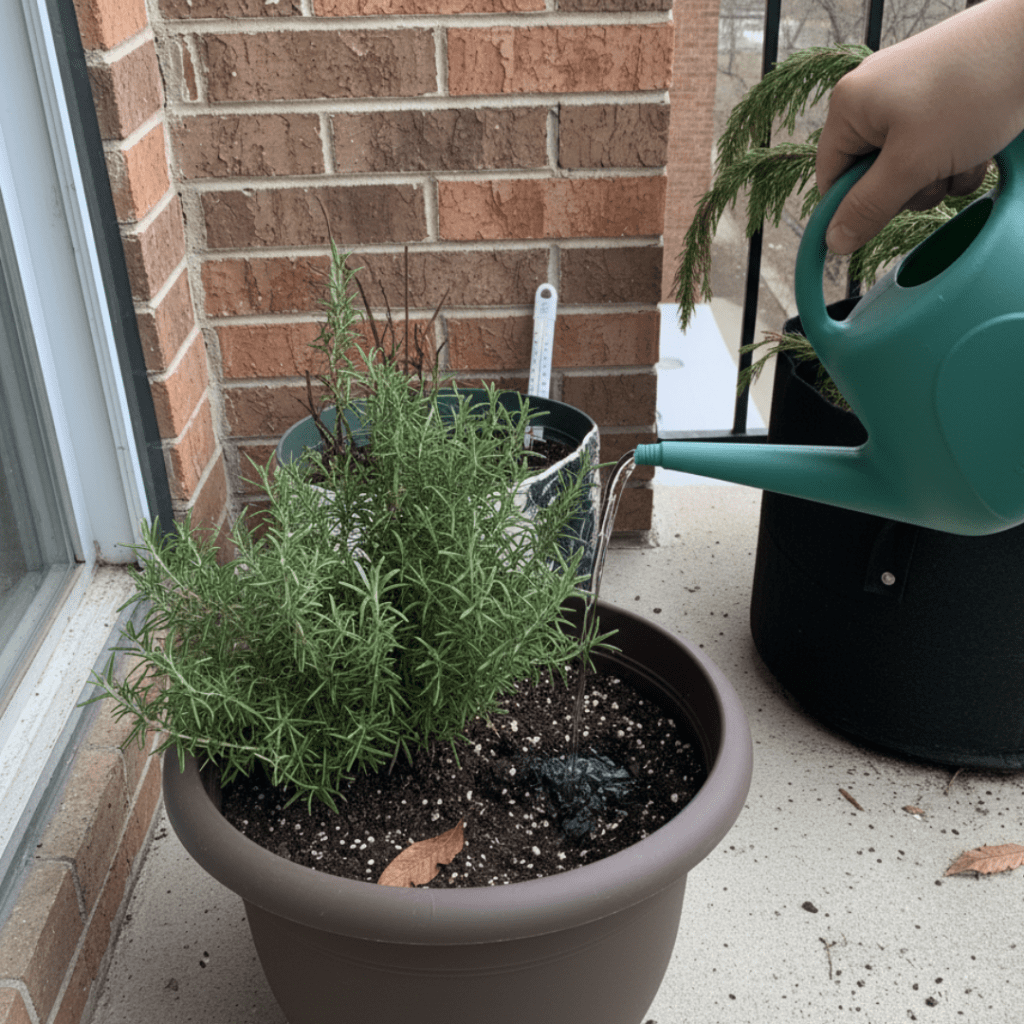

The fix is straightforward. Water your containers thoroughly whenever the soil thaws during a winter warm spell—even in January or February. If you can push a finger an inch into the soil and it feels dry, water it. On a sheltered balcony, the soil may thaw during sunny afternoons even when nighttime temperatures drop below freezing. I check my outdoor containers every five to seven days through winter, and I water about twice a month on average during the cold months. It feels counterintuitive, watering in winter, but it’s saved more of my plants than any amount of wrapping or covering ever did.

When the Microclimate Works Against You

I’d be doing you a disservice if I didn’t mention the other side of this coin. A warm microclimate can trick plants into breaking dormancy too early. I’ve seen balcony fig trees push new leaves in a warm February spell, only to have those tender shoots killed by a hard freeze in March. This premature growth exhausts the plant’s energy reserves and can weaken or even kill it over time. If your balcony runs very warm—consistently above 45 degrees Fahrenheit during late winter days—you may need to move your most sensitive plants to a cooler spot during those deceptive warm stretches, or shade them temporarily to keep them from waking up too soon.

Summer heat is the other concern. A south-facing balcony that’s a blessing in winter can become an oven in July, with reflected heat off brick and glass pushing temperatures above 110 degrees Fahrenheit at plant level. I’ve measured 115 degrees on a midsummer afternoon on a dark-floored balcony in the city. Plants rated for Zone 8 don’t necessarily love extreme heat—they need warmth in winter, not a furnace in summer. Move heat-sensitive containers to the shadier side of the balcony during the hottest months, or install a simple shade cloth along the railing for the peak afternoon hours. Balance is everything in balcony gardening, and understanding your microclimate means knowing both its gifts and its challenges.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: How do I know what hardiness zone my balcony actually is?

A: Place a soil thermometer in a container against your warmest wall and record the lowest reading at dawn during the coldest weeks of winter. Compare that minimum to the USDA zone chart—you’ll likely find your effective zone is one to two zones warmer than your area’s official designation.

Q: Can I push zones on a north-facing balcony?

A: North-facing balconies receive very little direct sun and miss out on the thermal charging that makes south-facing walls so effective. You might gain half a zone from wind protection alone, but significant zone-pushing really requires that south or southwest sun exposure.

Q: Do I need special containers for winter balcony gardening?

A: Avoid terra cotta and thin ceramic, which crack when frozen soil expands inside them. Resin, fiberglass, or thick-walled fabric grow bags hold up best, and anything at least 16 to 20 inches across provides better root insulation than smaller pots.

Q: How far can I realistically push my zone on a warm balcony?

A: One to two zones is realistic and reliable with good container insulation and wall placement. Pushing three zones is occasionally possible for very short cold snaps, but consistently growing plants rated three or more zones above yours leads to losses more often than not.

— Grandma Maggie