My neighbor Dorothy grew raspberries for forty years. Every summer she’d bring me a little basket — beautiful, sweet, and gone by mid-July. One afternoon I mentioned I’d just finished picking my honeyberries and she looked at me like I’d said something in a foreign language. “Honey-what?” she asked. I spent the next hour walking her through my back garden, watching her eyes go wide at the sea buckthorn blazing orange along the fence line, the serviceberry dripping with purple fruit, the aronia already darkening toward harvest. She had no idea any of it was possible up here in Zone 3. She’d spent four decades thinking raspberries were the only answer. They are wonderful, of course — I still grow them myself — but they are far from the whole story. There is a whole world of berry bushes that don’t just survive our brutal winters, they thrive in them. Let me show you.

Why Go Beyond Raspberries?

Raspberries are reliable, I will give them that. But they ripen all at once — usually in a frantic two-to-three-week window in late July — and then they are done. If you plant nothing else, you get one glorious burst and then spend the rest of the summer waiting for next year. After fifty years of gardening in cold climates, I’ve come to think of a diverse berry planting the way I think of a good choir: every voice comes in at a different moment, and together they fill the whole season with something wonderful. A well-planned berry garden in Zone 2 or 3 can give you fresh fruit from early June all the way through September, with very little of the coddling that southern gardeners assume cold-climate growing requires. Many of these plants actually need our hard winters — 800 to 1,200 or more chill hours below 45°F — to produce properly. Our long, brutal cold is not the obstacle. It is the secret ingredient.

Honeyberry (Haskap): First Fruit of the Season

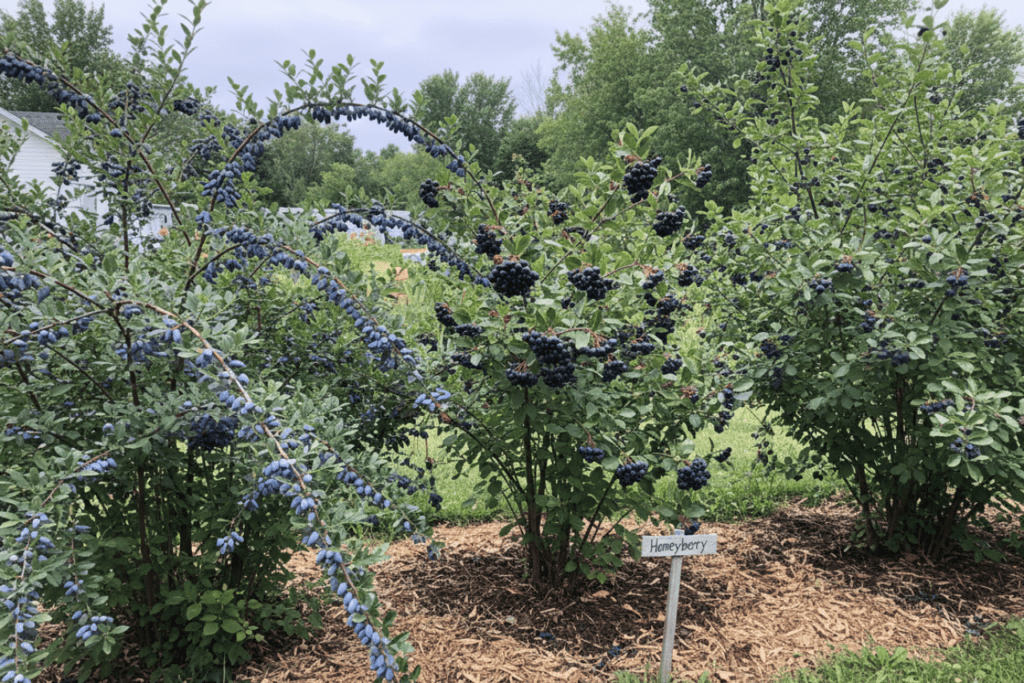

I planted my first honeyberry — also known as haskap — about fifteen years ago after reading a single sentence in a gardening catalog that described it as “the first fruit to ripen in the northern garden.” That was enough for me. After a winter that feels like it lasts nine months, the idea of picking fresh berries in early June, a full two to four weeks before strawberries even think about blushing, was impossible to resist. I was not disappointed. Honeyberries are hardy down to Zone 2, which means they laugh at temperatures that would kill most fruit plants outright. Their flower buds can survive a hard frost down to about 20°F (-6°C), so a late spring freeze that wipes out your apricot blossoms won’t even slow them down.

The one thing you absolutely must know before planting honeyberries is that you need at least two plants for cross-pollination, and they need to be compatible varieties — not just two random bushes from two different bins at the garden center. I learned this the hard way my first year, picking a grand total of about eleven berries from two plants that turned out to be the same variety under slightly different labels. Check with your nursery and plant pairs like ‘Tundra’ with ‘Borealis,’ or ‘Aurora’ with ‘Indigo Gem.’ Space them 3 to 4 feet apart for good air circulation. Once they’re established — usually after two to three years — a single mature bush can produce 5 to 10 pounds of fruit per season. The berries themselves taste like someone crossed a blueberry with a raspberry and then added a hint of elderberry; they are genuinely delicious fresh, and they freeze beautifully for pies and smoothies all winter long.

Sea Buckthorn: The Cold-Climate Superfood

I remember when I first saw a sea buckthorn in full fruit — a friend had one growing along her driveway and I nearly stopped the car. It looked like someone had studded every branch with tiny orange Christmas lights, packed so densely from stem tip to trunk that you could barely see the bark beneath. Sea buckthorn is rated to Zone 2, which makes it one of the hardiest fruiting shrubs you can possibly grow, and those brilliant orange berries are among the most nutritious foods you can eat — containing roughly 15 times the Vitamin C of an orange, along with Omega-7 fatty acids that are rare in the plant world. The plant looks dramatic in any season: silvery-green leaves in summer, blazing orange in fall, and a bold architectural silhouette against winter snow.

Here is what I want you to understand before you rush out to buy one: sea buckthorn comes in male and female plants, and you need both. One male plant can pollinate up to five female plants within a 30-foot radius, so plan accordingly. The male won’t produce berries, but without him your females won’t either. Plant them in full sun in well-drained soil — sea buckthorn absolutely will not tolerate wet feet and will sulk or die in heavy clay without amendment. Give them 6 feet of spacing at minimum, as they spread by suckering and can form a dense thicket over time, which is actually wonderful if you want a wildlife hedge or windbreak. The berries ripen in late August through September and are quite tart fresh — most gardeners process them into juice, syrup, or jam, or blend them into smoothies where their nutrition shines without the pucker.

Serviceberry (Saskatoon): The Native Gem

If I had to recommend just one unusual berry bush for a beginner in Zone 2 or 3, it would be the serviceberry — called Saskatoon in the Canadian prairies, where it has fed people for thousands of years. This is a plant so perfectly adapted to northern conditions that it doesn’t just survive here; it is from here. Native to the North American prairies, serviceberry grows from Zone 2 all the way to Zone 9 without complaint, tolerates part shade, handles dry soil once established, and produces beautiful white blossoms in early spring before almost anything else dares to bloom. In my experience, it is the most forgiving large fruiting shrub you can plant in a cold garden.

The berries ripen in June and July, depending on your location — typically about three weeks after the flowers fade — and they look and taste remarkably like blueberries, though with a hint of almond from the seeds. Indigenous peoples across the plains dried them like raisins for winter food, and they work equally well fresh, in pies, in jams, or dehydrated. A mature serviceberry can grow anywhere from 6 to 20 feet tall depending on the variety, so pay attention to the tag when you buy. Compact varieties like ‘Thiessen’ or ‘Northline’ stay around 6 to 10 feet and are excellent for smaller gardens. Space them 4 to 6 feet apart, plant in spring or fall, and within three to four years you’ll have a bush heavy with fruit every June. They are self-fertile, which means a single plant will produce — though yields improve with a second plant nearby.

Aronia (Chokeberry) and Highbush Cranberry: The Understudies

Not every berry is meant to be eaten straight off the bush, and I think that is worth saying plainly. Aronia, also called chokeberry, is rated to Zone 3 and produces spectacular clusters of dark purple-black berries in late summer that are absolutely packed with antioxidants — reportedly among the highest of any fruit you can grow. Fresh off the bush, though, they are extremely astringent. I’ve watched people pop one into their mouth at garden tours and their whole face changes shape. That is not a failure of the plant; it is just its nature. Processed into jam, juice, or wine, aronia is magnificent. I make an aronia-apple jelly every fall that disappears from the pantry shelf by February. The plant itself is nearly indestructible — it tolerates wet soil, dry soil, clay, and cold down to -40°F without batting an eye — and it grows to a tidy 3 to 5 feet tall, making it one of the most manageable shrubs in this list.

Highbush cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) deserves a mention in the same breath, though it is technically a viburnum rather than a true cranberry. It grows 8 to 10 feet tall, handles Zone 2 cold, and produces brilliant red berry clusters in September and October that look stunning against fall foliage. Like aronia, they are not pleasant raw — tart enough to make your lips disappear — but simmered with sugar they make a cranberry sauce that I genuinely prefer to the canned variety most people serve at Thanksgiving. Both aronia and highbush cranberry earn their keep not just as food plants but as ornamentals: aronia turns a fiery red-orange in fall, and highbush cranberry’s fruit clings to the branches all winter, feeding birds and looking beautiful against snow.

Building Your Berry Timeline

The real magic happens when you think about all of these plants together as a system rather than individual choices. In my back garden I’ve spent years arranging what I think of as a “berry calendar” — a succession of harvests that begins the moment the soil thaws and doesn’t end until the first hard freeze. Here is how the sequence works in a typical Zone 3 season. Honeyberries kick things off in early June, a full month before most people expect any fruit. Serviceberries follow in late June through July, overlapping briefly with the honeyberries at their tail end. Highbush blueberries — which I haven’t mentioned yet but absolutely belong in any Zone 3 garden where you can manage the pH, ideally between 4.5 and 5.0 — ripen through July and August. Aronia comes in August, sea buckthorn in late August through September, and highbush cranberry carries you right to the edge of frost in October.

For spacing, the general rule I follow is 3 feet between compact varieties like honeyberry and aronia, 4 to 6 feet for serviceberry and blueberry, and 6 feet or more for sea buckthorn and highbush cranberry. Plant in a location with good air circulation but sheltered from the worst north and northwest winds if possible — even Zone 2-hardy plants appreciate not having to fight a constant arctic blast. Amend your soil before planting: a 3-inch layer of compost worked into the top 12 inches will help most of these plants establish in their first year, which is when they are most vulnerable. After that first summer, cold-climate berry bushes are, in my experience, far more resilient than gardening books tend to suggest. They were made for this climate, and it shows.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Which unusual berry bush is easiest for a complete beginner?

A: Serviceberry, without question — it is native, self-fertile, and adaptable to a wide range of soils and light conditions. Plant one in spring, water well through its first summer, and you’ll be picking berries within two to three years.

Q: Do you need to plant multiples of each bush?

A: Honeyberries and sea buckthorn absolutely require compatible male and female plants — a single plant of either will produce little to nothing. Serviceberry and aronia are self-fertile and will produce on their own, though yields always improve with a second plant nearby.

Q: How long until I get my first real harvest?

A: Most shrubs give a small taste in year two or three but won’t hit their stride until year four or five. Plant with a ten-year mindset — the early years are about root development, and the real payoff comes later.

Q: How do you deal with birds stealing all the berries?

A: The only thing that works reliably is lightweight bird netting draped over the plants and secured at the base during the two to three weeks of peak ripeness. For sea buckthorn and highbush cranberry, I simply grow more than I need and share with the birds — those bushes produce so abundantly there is enough for everyone.

— Grandma Maggie