Bokashi Composting: The Japanese Fermentation Method That Handles Meat, Fish, and Dairy

I’ll be the first to admit, when my friend Patricia told me about fermenting her kitchen scraps in a sealed bucket under her sink, I thought she’d lost her mind. I’ve been composting for over fifty years using every method you can think of — hot piles, cold piles, worm bins, tumblers — and the idea of pickling food waste in a sealed container just sounded like a recipe for a smelly disaster. But Patricia kept raving about it, so I gave bokashi a try about eight years ago. I have not stopped since. What won me over was one simple fact: bokashi handles the scraps that every other composting method tells you to throw away. Leftover chicken, fish bones, cheese rinds, even that bowl of pasta nobody finished — it all goes in. Let me walk you through this beautifully simple Japanese fermentation method that might just change how you think about your kitchen waste.

Why Bokashi Works When Nothing Else Will

The magic behind bokashi is anaerobic fermentation — the same basic process that gives us sauerkraut, kimchi, and yoghurt. Instead of relying on oxygen and heat to break down food scraps the way a traditional compost pile does, bokashi uses a specific blend of beneficial microorganisms called effective microorganisms, or EM for short. These include Lactobacillus bacteria (the same family that turns milk into yoghurt), Saccharomyces yeast strains, and Rhodopseudomonas soil bacteria. Together, they ferment organic waste in an airtight, oxygen-free environment. This is why bokashi can safely process meat, fish, dairy, cooked food, and even small bones — things that would attract rats, raccoons, and all manner of unpleasantness in a traditional compost bin. In my experience, the smell is mild and slightly pickle-like, nothing at all like rotting food. It is not actual decomposition; it is fermentation, and that makes all the difference.

What You Need to Get Started

Getting set up for bokashi is refreshingly simple. You need two things: a bokashi bucket and bokashi bran. The bucket is an airtight container — usually a five-gallon pail — with a tight-fitting lid and a small spigot or drain valve at the bottom for collecting the liquid by-product. You can buy purpose-built bokashi bins for around forty to sixty dollars, or you can make your own from two nesting five-gallon buckets by drilling small holes in the bottom of the inner bucket for drainage. I’ve done both, and the commercial bins are a little more convenient, but the homemade ones work just as well.

Bokashi bran is the inoculant that makes the whole system work. It is typically wheat bran, rice hulls, or spent beer grain that has been infused with the EM culture and then dried. The drying puts the microorganisms into a dormant state, so when you sprinkle them over moist food scraps and seal the lid, they wake up and get right to work. A five-pound bag of bran usually costs around ten to fifteen dollars and lasts me through six to eight full buckets. I recommend buying two buckets from the start — one to fill while the other ferments — so you always have somewhere to put your scraps.

The Bokashi Process, Step by Step

Filling Your Bucket the Right Way

Start by sprinkling a generous handful of bokashi bran across the bottom of your empty bucket — about two tablespoons worth. Then add your kitchen scraps in a layer roughly two to three inches deep. Chop large pieces down a bit; you don’t need to dice everything finely, but halving a grapefruit rind or breaking up chicken bones makes fermentation more thorough. Sprinkle another tablespoon or two of bran over the scraps, then press everything down firmly with a potato masher, plate, or even a plastic bag filled with water. You want to eliminate air pockets — remember, this is an anaerobic process and trapped oxygen is the enemy.

Repeat this layering process each time you add scraps. I keep a small container on my countertop to collect a day’s worth of scraps, then add them to the bucket all at once rather than opening the lid multiple times. Every opening lets in oxygen, which can slow fermentation or cause off smells. After eight years, I have learned that one daily addition works best. Avoid adding anything already mouldy, as it carries competing bacteria that can throw off the fermentation. Also skip large beef or pork bones — they simply won’t break down within any reasonable timeframe — and steer clear of adding excess liquids or cooking oil.

The Fermentation Phase

Once your bucket is full, add a final generous layer of bran across the top — I use about three tablespoons — and seal the lid tightly. Now comes the easy part: you wait. Set the bucket somewhere out of direct sunlight, like a pantry, garage, or under the kitchen sink, and leave it sealed for a minimum of two weeks. I usually give mine a full three weeks in cooler weather, because fermentation slows down when temperatures drop below about 15°C (59°F). The bucket should not be opened during this period except to drain the liquid.

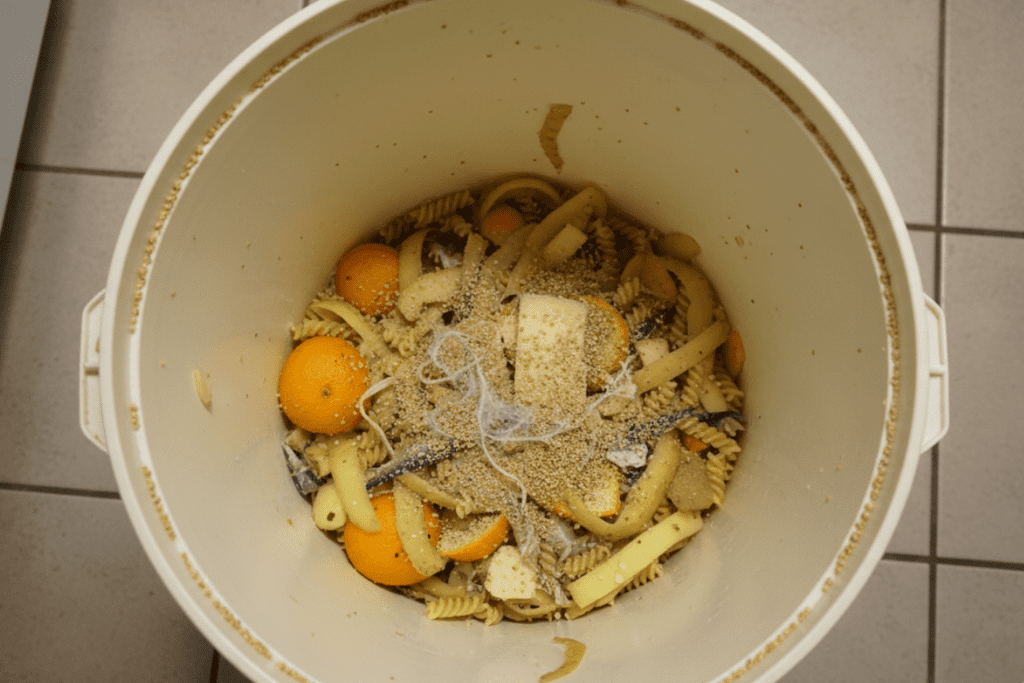

Every two to three days, open the spigot and drain off any liquid that has collected at the bottom. This is your bokashi leachate, and you want to remove it regularly because too much pooled liquid can cause the contents to go putrid rather than ferment cleanly. When the fermentation period is over, pop the lid and take a look. The food scraps will still be recognisable — you will see what used to be orange peels, potato skins, and bits of chicken — but they will look pickled, and the bucket should smell faintly sour and vinegary, a bit like a mild pickle brine. If you see white mould on the surface, that is perfectly normal and actually a sign of healthy fermentation. Blue or green mould, on the other hand, means something went wrong — usually too much air or not enough bran.

What to Do With Your Fermented Scraps

Here is the part that trips people up: bokashi fermentation is not the end of the process. It produces what is technically called pre-compost — material that still needs to finish breaking down in soil. The simplest method, and the one I use most often, is direct burial. I dig a trench or hole in my garden bed about eight to twelve inches deep, dump in the fermented contents, mix them with some of the surrounding soil, and backfill with at least six inches of dirt on top. Within two to four weeks, earthworms and native soil microbes will consume the pre-compost almost entirely. I have dug back into burial spots after three weeks and found practically nothing left, just rich, dark, worm-filled soil.

If you don’t have garden beds, you can create what is called a soil factory. Take a large storage tote or deep planter, fill it halfway with ordinary garden soil or potting mix, add the bokashi pre-compost, mix it through, and top with another four to six inches of soil. Leave it for three to four weeks, and the result is beautifully enriched planting soil you can use for containers, houseplants, or raised beds. This method works wonderfully for apartment gardeners who have a balcony. You can also add small amounts of bokashi pre-compost to an existing worm bin — worms absolutely love the stuff — but go slowly, perhaps a cup at a time, because the acidity can overwhelm them if you add too much at once. Wait at least two weeks after burying bokashi before planting directly in that spot, as the acids from fermentation can burn tender roots.

Making the Most of Bokashi Leachate

How to Use the Liquid By-Product

That brown liquid you drain from the spigot every few days is called bokashi leachate, and while some people call it “bokashi tea,” I should be upfront with you: the science on its value as a plant fertiliser is still mixed. Some studies show meaningful microbial benefits to the soil, while others suggest the nutrient levels are relatively modest compared to a balanced fertiliser. I have been using it for years, though, and I believe the microbial life it introduces to the soil has genuine value — especially for beds that have been heavily tilled or treated with chemicals in the past.

The standard dilution is one part leachate to one hundred parts water. In practical terms, that is about two teaspoons of leachate per litre of water, or roughly one tablespoon per gallon. Always apply it to the soil around your plants rather than directly on the foliage, because the acidity can damage leaves. Use the diluted liquid within twenty-four hours of draining it — the beneficial microbes begin dying off quickly once exposed to air. If you have more leachate than your garden can use, pour the undiluted liquid straight down your kitchen or bathroom drains. The microorganisms help break down grease and organic buildup inside the pipes. After five years of doing this, I can tell you my kitchen drain has never run cleaner.

Who Should Try Bokashi?

Bokashi is the only composting system I know of that works year-round in a small apartment kitchen with absolutely no outdoor space required during the fermentation phase. It originated in Japan, where living spaces are compact and traditional compost heaps are simply not practical. If you live in a flat, a condo, or anywhere without a garden, bokashi lets you divert all of your food waste — including the meat and dairy that curbside green bins sometimes reject — from landfill. The sealed bucket produces no odour beyond a faint sourness when you open it, and there are no fruit flies, no maggots, and no mess.

That said, bokashi is not a complete replacement for traditional composting if you have a large garden generating significant yard waste. It does not handle branches, woody prunings, or large volumes of leaves. I use bokashi alongside my regular compost system — the bokashi handles all the kitchen scraps including meat and fish, and the compost pile handles the garden trimmings and autumn leaves. Together, they make a beautiful team. The ongoing cost of bokashi bran is something to keep in mind as well. At ten to fifteen dollars per bag, you will spend roughly thirty to forty dollars per year if you run two buckets continuously. For me, the convenience and the ability to compost everything from my kitchen makes it well worth the investment.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Does bokashi composting smell bad?

A: When fermentation is going well, the bucket smells mildly sour and pickle-like — not unpleasant at all. A strong, rotten odour means something went wrong, usually too much air or not enough bran, and the batch may need to be discarded.

Q: Can I put cooked food and leftovers in a bokashi bucket?

A: Absolutely. Cooked rice, pasta, sauces, soups, meat, fish, bread, and dairy all go in. Just avoid large bones, excess cooking oil, and anything that is already visibly mouldy.

Q: How long does the entire process take from scraps to usable soil?

A: Plan on about two weeks to fill the bucket, two to four weeks of sealed fermentation, and another two to four weeks of breakdown after burying — so roughly six to ten weeks total from start to finish.

Q: Can I do bokashi composting in winter or in cold climates?

A: Yes. The fermentation phase happens indoors at room temperature, so cold weather is not a problem. If the ground is frozen, you can store sealed, fully fermented buckets in a garage or shed and bury the contents once the soil thaws in spring.

— Grandma Maggie