I’ll let you in on a little secret. For most of my gardening life, I thought composting had to be a production — turning piles every few days, checking temperatures with a long-stemmed thermometer, fretting over green-to-brown ratios like some kind of chemistry exam. And yes, hot composting works beautifully when you have the time and the back for it. But about twenty years ago, I stopped turning one of my piles for an entire summer. Life got busy, my knees were aching, and that pile just sat there in the corner behind the shed. When I finally poked through it the following spring, I found the darkest, most beautiful compost I’d ever made. That happy accident taught me something I now swear by: nature doesn’t need your help nearly as much as you think. Let me walk you through the method that changed everything for me.

Why Cold Composting Produces Such Remarkable Results

The word “lazy” gets attached to cold composting, and I understand why, but it sells the method short. Cold composting isn’t lazy — it’s patient. Instead of forcing decomposition with high heat, you’re letting the full cast of soil organisms do the work on their own schedule. And that slower pace carries a genuine advantage. Hot compost piles reach internal temperatures of 130 to 160 degrees Fahrenheit, which is wonderful for killing weed seeds and pathogens, but those temperatures also destroy many of the beneficial fungi that make compost truly special. Cold piles, by contrast, stay cool enough for fungi to thrive throughout the entire process. The result is a finished product with greater microbial diversity — particularly the kinds of decomposer fungi that continue improving your soil long after the compost is spread. I’ve noticed the difference with my own eyes over the years: cold compost has a richer, more earthy smell and a texture that’s almost velvety compared to the coarser crumble of my hot-composted batches.

Setting Up Your Cold Compost Pile the Right Way

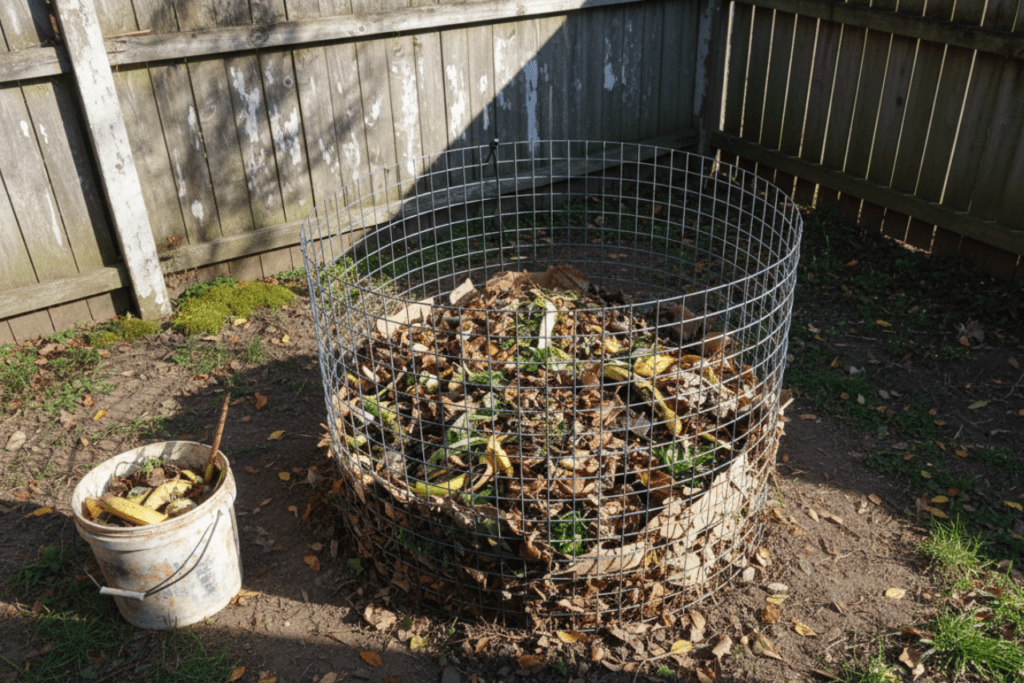

One of the things I love most about cold composting is that you don’t need fancy equipment. A bin helps keep things tidy, but it can be as simple as a cylinder of wire fencing about three feet across, a ring of stacked pallets, or even just a mound in a back corner. The important thing is that the bottom of your pile sits directly on bare soil. That ground contact is what allows earthworms, beetles, and all the tiny decomposers to move freely in and out of the pile, doing the heavy lifting you’d otherwise have to do with a pitchfork. I’ve tried bins with solid bottoms, and they work eventually, but nothing compares to the speed you get when the soil creatures have a direct invitation.

Choose a spot that gets partial shade if you can. Full sun in summer dries the outer edges of the pile too quickly, while deep shade stays too cool and damp in winter. I keep my cold pile behind my garden shed where it gets morning light and afternoon shade — a perfect balance. If you live somewhere with heavy rain, a loose-fitting lid or a tarp you can drape over the top during downpours will keep the pile from turning into a soggy, airless mess. You want the moisture level of a wrung-out sponge: damp throughout, but never dripping.

What Goes In — And What Stays Out

Cold composting is forgiving about ratios. You don’t need to obsess over the precise balance of carbon to nitrogen the way hot composting demands. That said, a rough guideline helps: aim for about three parts brown material to one part green material by volume. Browns are your carbon sources — dried leaves, shredded cardboard, straw, small twigs, newspaper torn into strips. Greens are your nitrogen sources — vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, fresh grass clippings, garden trimmings that haven’t gone to seed. I keep a small bucket next to my kitchen sink for scraps and empty it onto the pile every two or three days, tossing a couple handfuls of dried leaves on top each time. That simple habit is the entire maintenance routine.

Now, here’s where honesty matters. Because a cold pile doesn’t generate the sustained heat needed to kill pathogens and seeds, you need to be more selective about what you add. Keep out weeds that have gone to seed — I learned this the hard way when my entire flower border sprouted a carpet of lamb’s ear seedlings one spring. Leave out diseased plant material too; those fungal spores and bacterial problems can survive the cool decomposition process and spread when you use the finished compost. Meat, dairy, bones, and cooked food scraps should also stay out because without high temperatures to break them down quickly, they attract rodents and raccoons. Dog and cat waste is never safe for any home composting method, so keep that out entirely.

The One Trick That Speeds Everything Up

If there’s one thing that separates a six-month cold pile from an eighteen-month one, it’s particle size. The smaller you chop or shred your materials before adding them, the faster microorganisms can break them down. I run my fallen leaves through the lawn mower before raking them onto the pile — that alone can cut months off the process. Kitchen scraps get roughly chopped on the cutting board before they go into the bucket. Cardboard gets torn into pieces no bigger than my hand. Woody prunings thicker than a pencil go through a chipper or get set aside for the hot pile instead. You don’t need to be obsessive about this, but spending an extra minute or two chopping things smaller is the single most effective thing you can do to speed up cold composting without adding any real work to your week.

The other factor is moisture. During dry spells in summer, I give the pile a good soaking with the hose every week or two, just enough to dampen the top six to eight inches. In winter, I mostly leave it alone — rain and snow usually provide enough moisture, and the decomposition slows naturally in cold weather anyway. If your pile starts to smell sour or like ammonia, it’s too wet or too heavy on nitrogen-rich greens. The fix is easy: add a thick layer of shredded leaves or torn cardboard, about four to six inches, and let things rebalance over the next week.

Making the Most of Your Finished Cold Compost

How to Know When It’s Ready

Patience is the price of admission with cold composting, and I won’t pretend otherwise. Depending on your climate, the materials you’ve added, and how finely you’ve chopped things, you can expect finished compost anywhere from six months to a year and a half after you stop adding to the pile. The finished product should be dark brown to black, crumbly, and smell like a forest floor after rain. You shouldn’t be able to identify any of the original materials — if you can still see recognizable chunks of cabbage or whole leaves, it needs more time. I like to start a new pile once the first one reaches about three feet tall, then let the original sit undisturbed while the new one collects fresh material. Running two piles in rotation means you always have one cooking and one ready to harvest.

Before spreading cold compost across a garden bed, I always test it in a small area first, especially if my pile contained any materials I wasn’t entirely sure about. Spread a thin layer, about half an inch, over a two-foot-square section and watch for any weed germination over the next two to three weeks. If nothing sprouts that shouldn’t, you’re safe to use it freely. I apply cold compost as a top dressing about two inches deep around established plants and work it lightly into the top few inches of soil in new beds. Because cold compost is so rich in fungal life, it’s particularly good for perennial beds, fruit trees, and shrubs — plants that benefit from strong fungal networks in the soil around their roots.

Combining Cold and Hot Methods for the Best of Both Worlds

After all these years, I don’t think of cold and hot composting as competing approaches. I think of them as partners. My hot pile handles the weedy material, the diseased tomato vines, and the big batches of grass clippings that come all at once in early summer. My cold pile takes everything else — the steady trickle of kitchen scraps, the autumn leaves, the shredded paper and cardboard, the odds and ends that accumulate day to day. The hot pile gives me compost in six to eight weeks when I need it fast for spring planting. The cold pile gives me that deeply fungal, biologically rich compost that I spread in autumn to feed the soil over winter. Together, they keep my garden supplied year-round without my ever buying a bag of commercial compost from the garden center.

If you’re just starting out and the idea of managing two systems feels like too much, start with cold composting alone. It’s the most forgiving entry point into composting I know. You’ll make mistakes — too much grass clipping in one go, a dry spell you forgot to water through, a pile that seems to sit there doing nothing for months. But the beautiful truth about cold composting is that even your mistakes eventually turn into compost. Nature is more patient and more capable than we give her credit for. All you really have to do is pile things up, keep them reasonably moist, and wait. The garden will thank you for it.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I add citrus peels and onion scraps to a cold compost pile?

A: Yes, both are perfectly fine in a cold pile. They take longer to break down than softer scraps, so chop them into small pieces — roughly one-inch squares — and they’ll disappear within a few months.

Q: My cold pile hasn’t changed at all in three months. Is something wrong?

A: Probably not — it’s likely too dry or the pieces are too large. Soak the pile thoroughly and mix in some finely shredded leaves or torn cardboard. You should see visible change within four to six weeks after that.

Q: Do I need to add a compost starter or activator to a cold pile?

A: No. The bacteria and fungi needed for decomposition already exist on the materials you’re adding and in the soil beneath the pile. Save your money — a handful of garden soil tossed in now and then is all the inoculant you’ll ever need.

Q: Will a cold compost pile attract rats or other pests?

A: It can if you add meat, dairy, or cooked food. Stick to raw fruit and vegetable scraps, cover each addition with a layer of browns, and use a bin with a lid if rodents are common in your area. In twenty years of cold composting, I’ve had no pest problems following these rules.

— Grandma Maggie