After fifty years of growing everything from roses to rutabagas, nothing has brought me more pure delight than the morning I picked my first ripe mango from a tree sitting in a pot on my back porch. I thought you needed an orchard to grow tropical fruit, that you needed acreage and decades of patience. I was wrong. If you garden in USDA Zones 10 or 11—whether that means south Florida, coastal California, the Gulf Coast of Texas, or the warmer corners of Louisiana—you have a gift that most gardeners can only dream about. Your winters rarely, if ever, freeze. Your summers are long, sun-soaked, and warm. And that means a simple balcony, patio, or front stoop can become a genuine tropical fruit garden. Let me walk you through what’s actually possible, what’s worth your time, and where to start.

Why Container Tropical Fruit Thrives in Zones 10–11

The reason tropical fruit does so well in containers in Zones 10 and 11 comes down to one beautiful fact: you never have to rush anything indoors. In cooler zones, container fruit gardeners spend half their energy shuffling trees in and out of garages and sunrooms, worrying about one freak frost killing their investment. You don’t have that problem. Your potted mango or lemon can live outside 365 days a year, soaking up the consistent warmth these trees were born to love. The average winter low in Zone 10 stays between 30 and 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and in Zone 11 it rarely dips below 40. That means the entire range of subtropical and tropical fruit is on the table for you.

Containers also solve a problem I’ve seen trip up warm-climate gardeners for decades: poor native soil. Sandy coastal soils in Florida drain too fast and hold almost no nutrients. Heavy clay in parts of Texas can drown roots. When you grow in a well-prepared pot, you control the soil completely—the drainage, the organic matter, the pH. I’ve watched gardeners with the worst yard soil in the neighborhood pull the best fruit off potted trees simply because they got the growing medium right from the start.

Dwarf Citrus: Your Easiest Starting Point

If you’re brand new to container fruit growing, I always say start with citrus. I’ve been growing dwarf citrus in pots for over twenty years, and they remain the most forgiving, most rewarding trees a beginner can try. The Improved Meyer Lemon is my number one recommendation for first-timers. It’s a self-pollinating hybrid between a lemon and a mandarin, which means the fruit comes out sweeter and juicier than grocery-store lemons, with a thin, almost orange-tinted skin. A grafted dwarf Meyer can produce fruit in its very first or second year, and in Zones 10–11 it will bear almost year-round. Start a young nursery tree in a 7-to-10-gallon pot and graduate it to a 15-gallon container as it matures. It tops out around six to eight feet tall in a pot, and with a little annual pruning, you can keep it even more compact.

Beyond Meyer lemons, several other citrus varieties are container champions. Bearss Seedless Lime is wonderfully productive and trouble-free. Meiwa Kumquats stay naturally compact and produce small, sweet fruit you eat skin and all—perfect for a balcony where space is tight. Calamondin is another favorite of mine for tiny spaces, since it stays quite small and produces tart little fruits wonderful in marinades and drinks. For all container citrus, the rules are the same: use a fast-draining potting mix with a slightly acidic pH between 5.5 and 6.5, place the tree where it gets at least six to eight hours of direct sun, and feed with a citrus-specific fertilizer every two to three weeks during spring and summer. Water deeply when the top two inches of soil feel dry, but never let the pot sit in standing water. I learned that lesson the hard way with a lime tree I nearly drowned my first year.

Mangoes in a Pot—Yes, Really

This is the one that shocks people. When I tell fellow gardeners I grow mangoes on my patio, I get the same wide-eyed look every time. Traditional mango trees can reach over a hundred feet tall in their native habitat, so the idea of one fitting in a pot sounds absurd. But the world of “condo mangoes”—compact dwarf varieties bred specifically for container growing—has changed everything. These trees produce full-sized, gorgeously flavored fruit on plants you can maintain at just six to ten feet tall with annual pruning. The trick is choosing the right variety and always buying grafted trees, never seedlings. A mango grown from a pit can take eight years or more to fruit with no guarantee it ever will. A grafted dwarf can bear fruit in as little as two to three years.

My favorite condo mango varieties, after years of experimenting, are Ice Cream, Pickering, and Cogshall. Ice Cream stays remarkably compact at around six feet and produces creamy, rich fruit that lives up to its name. Pickering is bushy and naturally well-shaped, bearing mangoes with a delightful coconut-mango flavor. Cogshall is extremely compact, tops out around eight feet, and has excellent disease resistance—a real plus in humid climates like Florida. If you enjoy Thai-style mangoes, Nam Doc Mai is widely considered one of the best for pot culture, producing sweet, elongated fruit. Plant your dwarf mango in a 15-gallon pot to start and plan to upgrade to a 25-to-30-gallon container within a couple of years. Use a light, well-draining mix rich in organic matter with a slightly acidic to neutral pH of 5.5 to 7.5. Give the tree your sunniest spot. During active growth, fertilize with a balanced formula, then switch to something higher in phosphorus and potassium when blooming starts. Prune new shoots when they reach about 20 inches to encourage branching and fruit production.

More Tropical Container Winners Worth Growing

Figs, Guavas, Papayas, and Passion Fruit

Citrus and mangoes get the most attention, but your balcony has room for so much more. Figs are one of the easiest fruit trees you can grow in a container, full stop. Every variety of fig tolerates container life well, and here’s a secret I learned decades ago: when a fig’s roots are confined in a pot, it often produces more fruit, not less. Varieties like Celeste and Little Miss Figgy stay naturally compact, tolerate heat beautifully, and resist most pests and diseases. I’ve grown a Little Miss Figgy on a narrow apartment balcony that gets just five feet of railing space, and it rewarded me with handfuls of sweet figs every summer. Give figs full sun, avoid overfeeding with nitrogen, and water when the soil dries out. That’s about all they ask.

Guavas are criminally underrated for container growing. They’re ornamental, fragrant, and the fruit is packed with flavor. Apple guava produces the largest fruits—sometimes as big as a softball—while strawberry guava stays smaller and more compact. Pineapple guava, technically a different species called feijoa, is especially forgiving and handles heat and occasional cool snaps. All do well in Zones 9 through 11 and grow happily in a 15-to-20-gallon pot. I fell in love with guavas the first time I smelled the blossoms, and the fruit sealed the deal.

Dwarf papayas are a showstopper. They look dramatic with those big tropical leaves, and varieties like TR Hovey stay around six to seven feet tall in a container and can produce fruit within the first year. They do need copious water and regular feeding, so they’re a bit more hands-on than citrus or figs, but the payoff—a tree-ripened papaya that tastes nothing like the bland ones from the grocery store—is worth the extra attention. Passion fruit vines are another possibility, though they need a sturdy trellis or railing to climb. The Black Knight variety is a dwarf that does well in containers, producing tangy-sweet purple fruit. Passion fruit vines are vigorous growers that can put on 15 to 20 feet in a single season, so plan on regular pruning and a large pot—at least two to three times the size of whatever the vine came in.

Getting the Container Basics Right

Pots, Soil, and the Watering Rhythm That Makes Everything Work

After all these years, I can tell you that the pot you choose matters almost as much as the tree you put in it. For any fruit tree that will live more than a couple of years in a container, I recommend starting with a minimum of a 15-gallon pot and planning to move up to 25 or even 30 gallons as the tree matures. Wood, plastic, and ceramic all work, but I’m partial to lightweight plastic or resin for balconies because the combination of tree, soil, and water gets heavy fast. Put your pot on a rolling plant dolly if you think you’ll ever need to shift it around. Drainage holes are absolutely non-negotiable—I cannot say this strongly enough. No drainage means drowned roots, and drowned roots mean a dead tree, no matter how good everything else is.

For soil, I use a lightweight mix that drains fast but holds enough moisture to keep roots happy between waterings. My go-to recipe is roughly 40 percent high-quality compost, 40 percent bark-based potting mix, and 20 percent perlite or pumice for aeration. Some gardeners add coarse sand, which also works. Avoid using garden soil straight from the yard—it compacts terribly in a container and often brings pest and disease problems with it. The single biggest mistake I see container fruit growers make is watering on a schedule instead of by feel. Stick your finger two inches into the soil. If it’s dry, water deeply until it runs from the drainage holes. If it’s still moist, wait another day. Container trees in full sun during a Zone 10 summer might need water every single day. In winter, once or twice a week is usually enough. Feed with a slow-release fertilizer formulated for fruit trees at the beginning of spring, then supplement with a liquid feed every two to three weeks during the growing season. Cut back fertilizing in late fall and winter when growth slows.

The Mistakes I Made So You Don’t Have To

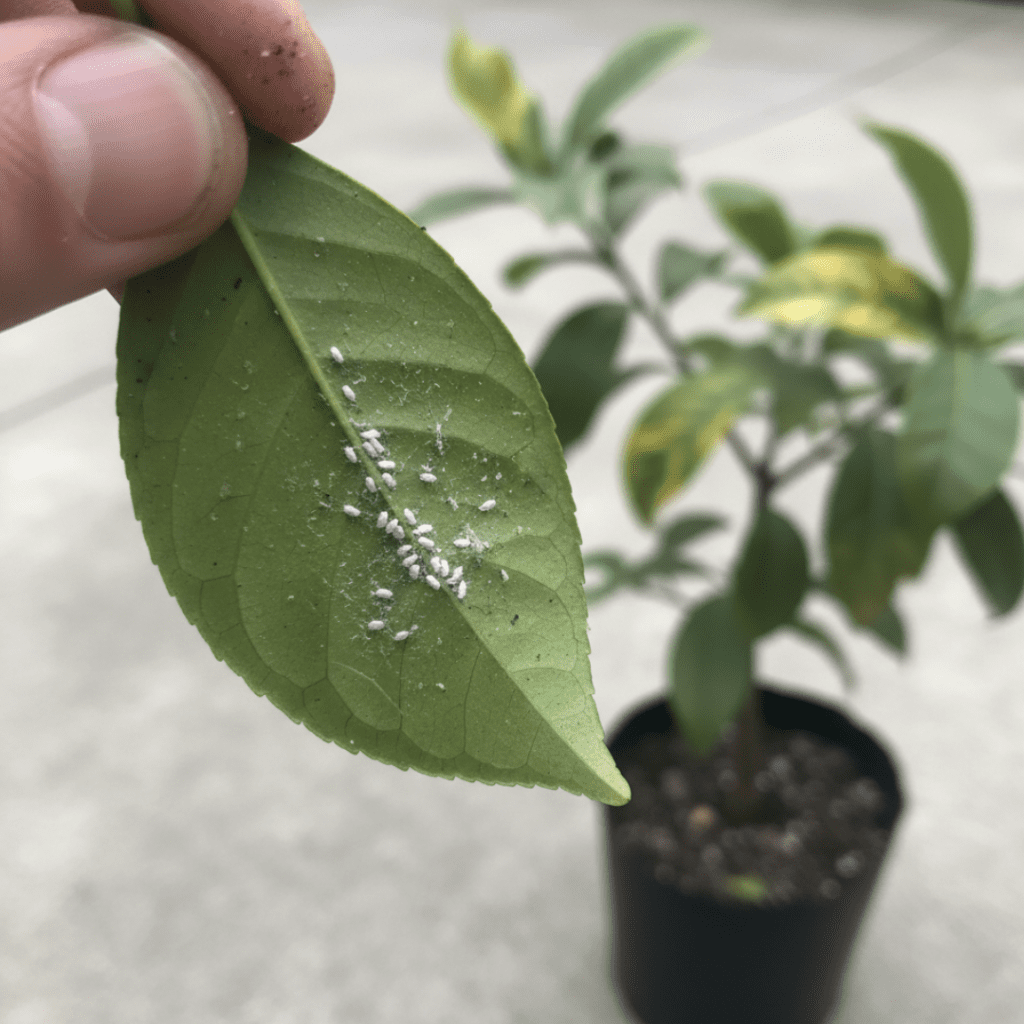

I wish someone had sat me down and told me a few things before I started growing tropical fruit in containers. First, don’t try to grow a tree from seed when you want fruit. I wasted years nursing a mango seedling that never produced a single fruit. Always buy grafted trees from a reputable nursery. Second, bigger pots are almost always better. I used to start trees in cute little decorative planters, and every single one stalled out within months because the roots had nowhere to go. Give your trees room. Third, don’t skip the fertilizer. A tree in the ground can send roots far and wide to find nutrients. A tree in a pot only has what you give it. And fourth—the one that cost me the most heartache—don’t ignore pests just because they start small. Whiteflies, scale, mealybugs, and spider mites all love tropical fruit trees. Inspect the undersides of leaves every week or two and treat early with diluted neem oil or a strong spray of water. A small problem on Monday becomes a crisis by Friday in warm weather.

One more piece of hard-won wisdom: repot young trees every one to two years into a slightly larger container with fresh potting mix. Once a tree reaches its final pot size—usually around 25 to 30 gallons—you can maintain it there for years by refreshing the top few inches of soil annually and root-pruning every two to three years. Root pruning sounds intimidating, but it’s just a matter of sliding the root ball out, trimming an inch or two off the outer edges with a clean knife, and repotting in fresh mix. I’ve kept a Meyer lemon healthy and fruiting in the same pot for over five years this way.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: What’s the single best tropical fruit tree for a beginner with a small balcony?

A: An Improved Meyer Lemon in a 10-to-15-gallon pot. It’s self-pollinating, produces fruit within a year or two, stays compact with light pruning, and forgives most beginner mistakes.

Q: Can I really grow a mango tree in an apartment container?

A: Yes, as long as you choose a grafted dwarf variety like Ice Cream or Pickering and give it a 15-to-30-gallon pot with full sun. These “condo mangoes” stay six to ten feet tall and produce full-sized fruit within two to three years.

Q: How often should I water container fruit trees during a Zone 10 summer?

A: Check the soil daily. If the top two inches feel dry, water deeply until it drains from the bottom. In peak summer heat, that can mean watering every single day for trees in full sun.

Q: Do I need two trees for pollination?

A: Most of the best container tropical fruits—citrus, mangoes, figs, and papayas—are self-pollinating, so a single tree will produce fruit on its own. Passion fruit is the exception; some varieties benefit from a second vine for cross-pollination.

— Grandma Maggie