After fifty years of tending herb gardens in the Mid-Atlantic, I’ve learned one thing the hard way: not every Mediterranean herb earns a permanent spot in the ground. I’ve buried more rosemary plants than I care to admit, mourned lavender that dissolved into mush after a February freeze, and watched beautiful sage simply vanish under a blanket of wet spring snow. But I’ve also discovered which varieties are genuinely tough enough to survive our zone 6 and 7 winters—and which ones just need a little extra help to make it through. The truth is, with the right cultivar selection, proper siting, and a few tricks I’ve picked up over the decades, you can grow a gorgeous, productive Mediterranean herb garden that comes back stronger every spring. Let me walk you through what actually survives out here, variety by variety, so you stop wasting money on plants that were never going to make it.

Why Variety Selection Matters More Than Anything Else

I can’t tell you how many gardeners come to me frustrated, saying “I just can’t grow rosemary” or “lavender hates me.” Nine times out of ten, the problem isn’t their skill—it’s their cultivar. A generic rosemary from the supermarket is probably hardy to zone 8 at best, and no amount of mulching or praying will carry it through a zone 6 January. The same goes for French lavender, which looks stunning but simply cannot handle temperatures below about 15°F. In my experience, the difference between a Mediterranean herb that thrives in our Mid-Atlantic winters and one that turns to brown mush by March comes down to three things: choosing a cultivar bred for cold tolerance, giving it soil that drains like a sieve even in February, and siting it where it gets protection from drying winter winds. Get those three right, and you’ll be amazed at what survives.

Rosemary: The Trickiest One to Overwinter

Let’s start with the herb that breaks the most hearts in our region. Most rosemary varieties are rated for zone 8, meaning they start suffering serious damage once temperatures dip below about 10°F. In zone 6, where winter lows can plunge to -10°F, that’s a death sentence for the average rosemary bush. But there are a few cultivars that have proven themselves, and after losing more rosemary plants than I can count, I’ve narrowed my recommendations to two.

‘Arp’ is the gold standard for cold-hardy rosemary, and for good reason. It was discovered growing in Arp, Texas, back in 1972, and it has thin, silvery-green needles that seem to help it conserve energy through cold spells. I’ve had an ‘Arp’ rosemary survive three consecutive zone 6 winters planted against my south-facing foundation wall with 5 to 6 inches of wood chip mulch piled over the roots each November. The trick with ‘Arp’ is drainage—I mixed a full shovel of coarse builder’s sand and another of pea gravel into the planting hole, and I never let water pool around the base. Wet, poorly drained soil in winter will rot the roots faster than any cold snap.

‘Madalene Hill’ is the other cultivar I trust in zone 6. It’s a compact, dark-green variety that reaches about 3 feet tall and produces lovely pale blue-purple flowers in summer. It’s slightly less cold-tolerant than ‘Arp’ in my experience, so I give it an extra layer of burlap wrap and make sure it’s tucked into the warmest microclimate I can find. For zone 7 gardeners, your options open up a bit—’Salem’ and ‘Alcalde Cold Hardy’ can both make it with decent winter protection. But I’ll be honest: even with the hardiest varieties, rosemary in zones 6 and 7 is always a bit of a gamble. A string of mild winters will lull you into confidence, and then one brutal cold snap takes the whole plant. That’s why I always keep a backup cutting rooted in a pot indoors, just in case.

Lavender: Pick the Right Species and You’re Golden

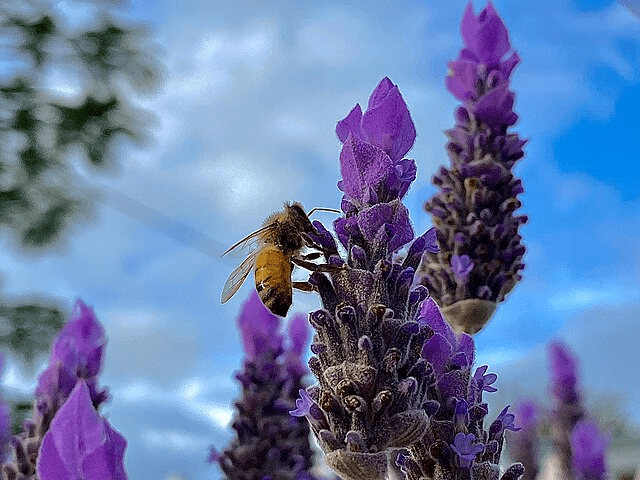

Lavender is a much happier story than rosemary in the Mid-Atlantic, as long as you choose English lavender or its hybrids. I’ve been growing ‘Hidcote’ and ‘Munstead’ for over fifteen years now, and they come back reliably every single spring. The key to understanding lavender hardiness is knowing there are distinct species, and they vary enormously in cold tolerance. English lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) is the toughest, hardy down to zone 4 or 5 depending on the variety. French lavender and Spanish lavender? Beautiful, but not long for our winters. I treat those strictly as annuals or container plants that come indoors by late October.

My go-to recommendations for zone 6 and 7 lavender start with ‘Hidcote,’ a classic English cultivar with deep purple flowers and a compact, bushy habit that stays about 24 inches tall and wide. It’s an Award of Garden Merit winner and one of the most cold-tolerant lavenders you can plant. ‘Munstead’ is another reliable English variety—slightly smaller and earlier blooming, perfect for edging or low borders. Both of these have survived my zone 6b winters without any special protection beyond good drainage and full sun exposure of at least six hours per day.

For gardeners who want bigger plants with longer flower stems, the hybrid lavandins are worth exploring. ‘Phenomenal’ is the standout here—it was specifically bred for cold hardiness and humidity tolerance, and it has become enormously popular with both home gardeners and commercial lavender farmers across the eastern United States. ‘Grosso’ is another lavandin hybrid known for its dark flowers and impressive zone 6 cold hardiness. These hybrids bloom a bit later than English types, from midsummer into fall, which actually extends your lavender season beautifully. I grow both English and hybrid lavenders side by side and get fragrant blooms from late spring clear through August. One critical tip I’ve learned the hard way: never mulch lavender with bark or organic mulch that holds moisture. Use pea gravel or coarse sand around the base. Root rot from wet winter soil kills far more lavender plants in our region than cold temperatures ever do.

Sage: The Easiest Mediterranean Herb to Overwinter

If rosemary is the diva of the Mediterranean herb world, common sage is the dependable workhorse. Salvia officinalis is hardy all the way down to zone 4 in most cases, which means our zone 6 and 7 gardens are well within its comfort zone. I’ve had sage plants persist for four or five years before they start getting too woody and lose their punch. The standard green-leaved common sage is the toughest, but I also grow ‘Berggarten,’ a broad-leaved variety that rarely flowers and stays compact and productive. It’s my favorite for cooking because those wide, velvety leaves have a wonderful concentrated flavor.

The ornamental sage varieties are slightly less hardy but still very doable in our area. ‘Purpurascens,’ with its gorgeous purple-tinged leaves, and ‘Icterina,’ which has cheerful green-and-chartreuse variegated foliage, are both rated to zone 6. I use them as much for their beauty in the border as I do for cooking. One thing to keep in mind with all sage: it’s technically a short-lived perennial. After about three to four years, the stems get increasingly woody and the leaf production drops off. When that happens, I just start a fresh plant from a cutting or division—sage roots so easily from stem cuttings that it’s almost foolish to buy a new plant when the old one declines. After the first hard frost, I leave the woody stems standing through winter because they help protect the crown, and I don’t cut back until I see fresh new growth emerging in spring.

Thyme and Oregano: The Quiet Survivors

I almost hate to draw attention to thyme and oregano because they’re so easy that they might make other herbs jealous. English thyme, French thyme, and creeping thyme are all reliably hardy to zone 4 or 5, which means they barely notice our Mid-Atlantic winters. My patch of common English thyme has been in the same spot for eight years, and it just keeps expanding into a fragrant, low-growing carpet that requires almost nothing from me. Greek oregano is similarly bulletproof—hardy to zone 5, drought-tolerant, and productive enough that one plant supplies my kitchen from June through October.

The only trick with these two is understanding what happens in winter. The tall summer stems of oregano will die back and defoliate by late autumn, but if you look closely at the base, you’ll see fresh, low-growing rosettes hugging the ground. That’s next year’s growth getting established, and it’s perfectly normal. Thyme holds its tiny leaves through most of the winter, though they can look a bit ragged after ice storms or prolonged cold snaps. I lay a few evergreen boughs over my thyme and oregano in December—nothing elaborate, just enough to break the drying winter wind. Come spring, I remove the boughs, trim back any brown or dead stems, and within two to three weeks, both herbs are pushing out lush new growth. These are the herbs I recommend to every beginning gardener in our region because they’re genuinely difficult to kill.

Winter Protection That Actually Works

After decades of experimenting, I’ve settled on a winterizing routine for my Mediterranean herbs that takes about an hour each fall and pays enormous dividends. First, I stop fertilizing all herbs by early August—any late-season nitrogen encourages tender new growth that won’t have time to harden off before frost. I do my last major pruning by early September for the same reason, though light harvesting for the kitchen continues until the first hard freeze. For rosemary and lavender, I mound 4 to 6 inches of mulch over the root zone in late November, using pine needles, straw, or shredded leaves. I avoid heavy bark mulch because it holds too much moisture against the crowns.

Siting is everything. The warmest microclimates in your yard are along south-facing or west-facing walls, where your home’s foundation radiates stored heat back into the soil. I’ve measured a full zone-and-a-half temperature difference between an exposed bed in the middle of my yard and a sheltered spot against my brick house. That’s the difference between zone 6 and zone 7b, and it can mean the difference between a living rosemary and a dead one. Wind protection matters too—harsh, drying winter winds desiccate evergreen herbs like rosemary, lavender, and thyme much faster than cold air alone. A burlap screen, a nearby evergreen shrub, or even a cold frame can make all the difference. I keep one small cold frame dedicated to overwintering my most precious rosemary, and it has been the single best investment I’ve made in herb gardening.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I overwinter rosemary outdoors in zone 6 without any protection?

A: It’s risky even with the hardiest varieties like ‘Arp.’ I always recommend a south-facing wall, excellent drainage, and 5 to 6 inches of mulch over the roots at minimum. A cold frame or burlap wrap gives you much better odds.

Q: Why does my lavender die every winter even though it’s supposed to be hardy?

A: In our region, the culprit is almost always wet soil rather than cold. Lavender roots rot quickly in soggy winter ground. Make sure you’re growing it in sharp-draining soil and never mulching with moisture-holding organic material right against the crown.

Q: Is there any variety of French or Spanish lavender that survives zone 6?

A: Not reliably in the ground. French and Spanish lavenders are rated zone 7 to 9 at best. Grow them in containers so you can bring them inside before temperatures drop below about 20°F.

Q: When should I prune my sage and thyme in fall?

A: Do your last significant pruning by early September so new growth has at least 4 to 6 weeks to harden before the first hard freeze. Light harvesting after that is fine, but avoid cutting back hard—save major pruning for spring once you see fresh growth emerging.

— Grandma Maggie