After fifty years of digging in the dirt, I can tell you that few things test a gardener’s patience quite like a short growing season. I spent my early years in a Zone 3 climate, watching June frosts wipe out seedlings I’d been babying on my windowsill since March. It felt like the calendar was working against me every single year. Then I discovered the quiet power of containers, and everything changed. Those pots on my south-facing deck gave me a two-week head start in spring and let me drag tomatoes into September when frost threatened overnight. If you’re gardening where winter temperatures plunge to minus thirty or forty degrees Fahrenheit and your frost-free window barely reaches ninety days, containers are not a compromise. They’re a genuine strategy. Let me walk you through exactly how I’ve pulled big harvests from small pots in the coldest corner of the country.

Why Containers Give Cold-Climate Gardeners a Real Advantage

The science behind containers in cold climates is simpler than most people think. When you grow in a pot, there is far less soil mass that needs to heat up before your plants can really take off. In-ground soil in Zone 3 can still be cold and sluggish well into June, but a dark-colored five-gallon container sitting on a sunny deck can reach planting temperature a full week or two before that same soil in the ground warms up. I’ve measured the difference with a soil thermometer many times, and it’s not unusual to see a ten-degree Fahrenheit gap between container soil and garden bed soil in late May. That warmth isn’t just a convenience. Soil temperature drives root growth, nutrient uptake, and fruit set, especially in heat-loving crops like tomatoes and peppers. In my experience, the difference between a pepper that sets fruit and one that just sits there sulking often comes down to those extra degrees in the root zone.

There’s another advantage that I think gets overlooked: mobility. When I hear a frost warning in early June or late August, I don’t panic. I wheel my container cart into the garage or up against the south wall of the house, where radiant heat from the foundation buys me a few critical degrees overnight. You simply cannot do that with an in-ground garden. In a ninety-day season, every single frost-free day counts, and containers let you fight for every one of them.

Choosing the Right Containers for Extreme Cold

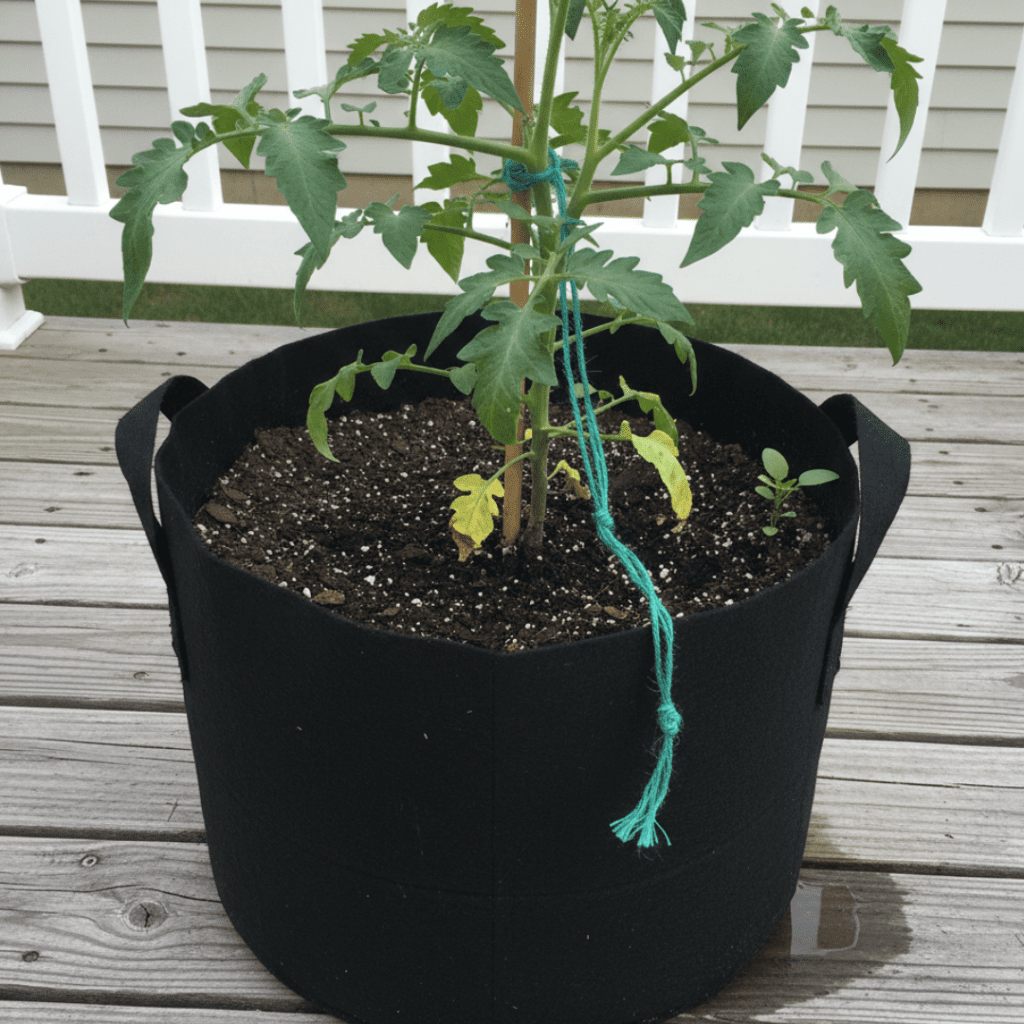

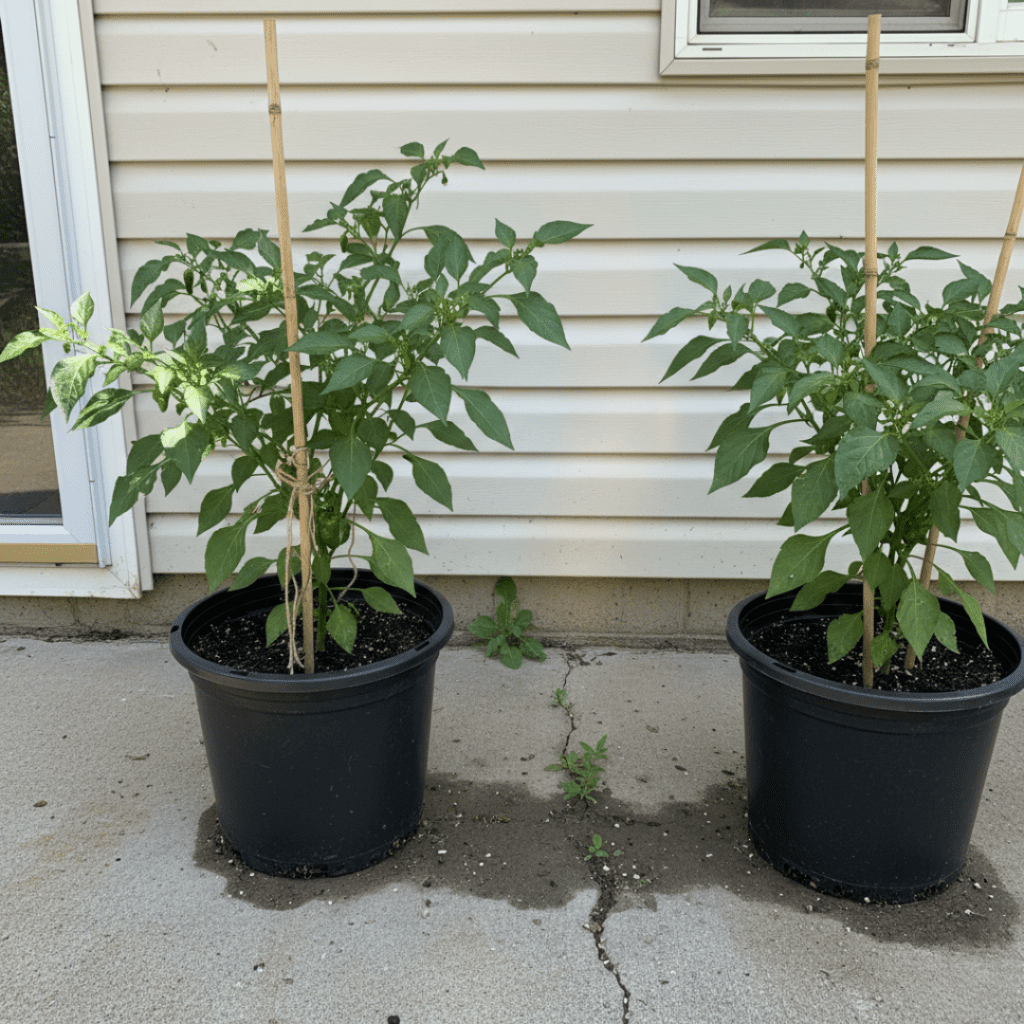

Not every container belongs in a Zone 3 garden, and I learned that the hard way. My first winter, I left a beautiful ceramic pot outside and found it cracked into three pieces by April. Freeze-thaw cycles are brutal on rigid materials, so if you plan to leave anything outdoors over winter, stick with thick-walled plastic, resin, or fabric grow bags. For the actual growing season, though, I’ve become a devoted fan of dark-colored plastic pots and fabric grow bags in the ten- to fifteen-gallon range. Dark colors absorb sunlight and convert it directly into warmth in the root zone, which is exactly what cold-climate vegetables need.

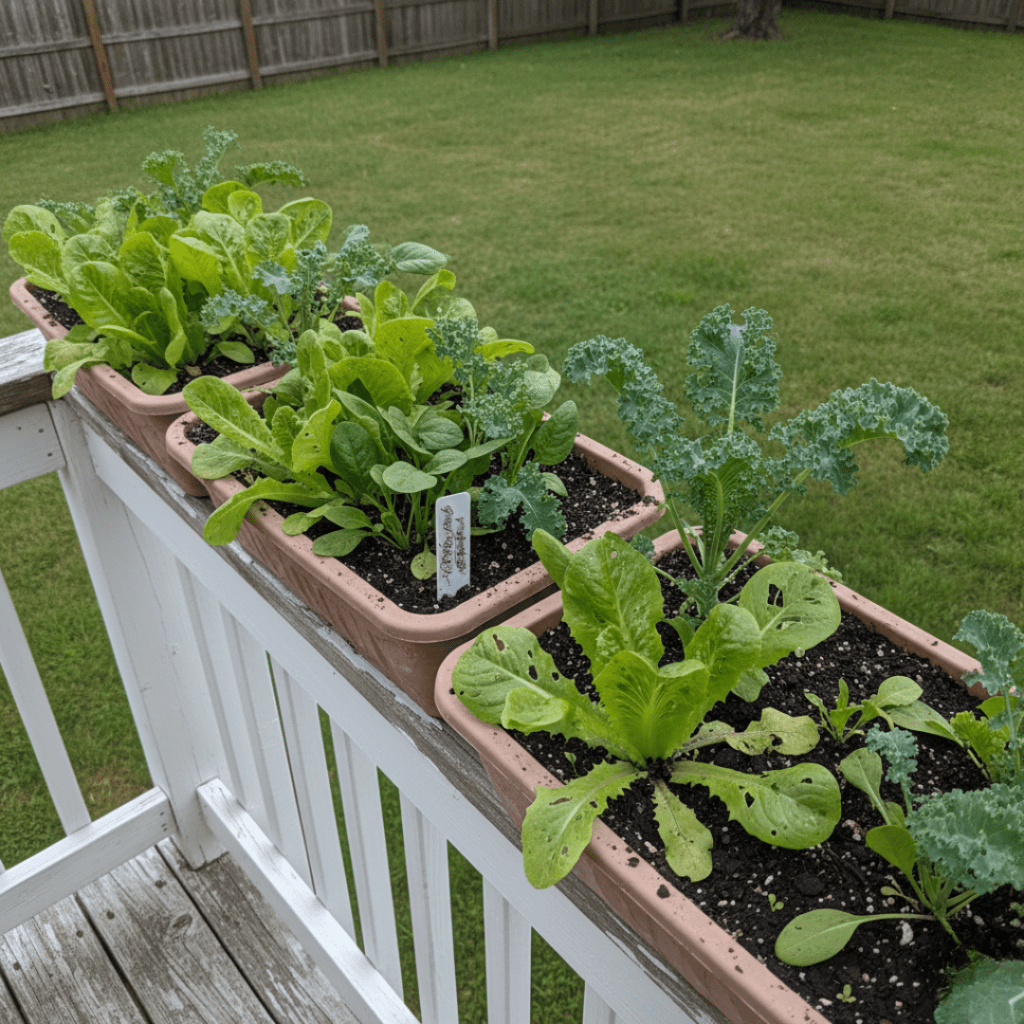

Size matters more than most beginners realize. A five-gallon pot is the bare minimum for a single tomato or pepper plant, but I’d recommend going up to ten gallons if you have the space. The larger soil volume holds warmth longer after sundown and doesn’t dry out as quickly during those hot July afternoons that Zone 3 does actually get. For leafy greens and herbs, a wide, shallow container around three to five gallons works perfectly. I use long window-box-style planters for lettuce and spinach, setting them on the deck railing where they catch every minute of sun. Whatever you choose, make sure it has good drainage holes. Waterlogged soil stays cold, and cold wet roots are a recipe for rot in any climate.

The Best Vegetables for Short-Season Containers

After decades of trial and error, I’ve divided my container crops into two categories: the reliable workhorses that produce no matter what, and the heat-lovers that need a little extra coaxing but are absolutely worth the effort.

Cool-Season Champions That Almost Grow Themselves

Lettuce, spinach, kale, and radishes are the backbone of my container garden every single year. These crops actually prefer the cooler temperatures that Zone 3 delivers, and they can go into containers a good two to three weeks before the last frost date. I start sowing loose-leaf lettuce and radish seeds directly into containers around mid-May, covering them with a simple sheet of frost cloth on cold nights. Radishes are particularly satisfying because you can harvest them in as little as twenty-five days and then replant the same container every two weeks for a continuous supply right through August. Kale and Swiss chard are long-season producers that I transplant into twelve-inch pots in early June. One well-fed kale plant in a container can keep giving you harvests from July through the first hard freeze in September, and I’ve had plants survive light frosts of twenty-eight degrees without any protection at all.

Peas are another winner, though they need a little support. I use a simple trellis of bamboo stakes and twine in a ten-gallon pot and sow sugar snap peas directly into the container in mid-May. They’ll handle light frost without complaint and usually start producing pods by early July. Bush beans go in after the last frost around June first, and varieties like Provider or Contender mature in about fifty days, well within the Zone 3 window.

Heat-Lovers Worth the Extra Effort

Tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers are the crops that most Zone 3 gardeners dream about, and containers are honestly the best way to grow them this far north. The key is choosing early-maturing varieties and starting seeds indoors in late March or early April, a full eight to ten weeks before transplanting. For tomatoes, I swear by Early Girl, Glacier, and Sub Arctic Plenty, all of which can produce ripe fruit in fifty-five to sixty-five days from transplant. I grow them in ten-gallon black fabric bags on my sunniest deck spot, and they consistently ripen by late August. Peppers need even more warmth, so I choose compact varieties like Ace, King of the North, or Early Jalapeño and keep them in dark pots pushed right up against the south-facing wall of the house, where reflected heat can add five to eight degrees on a sunny day.

Cucumbers do surprisingly well in Zone 3 containers if you pick the right variety. I look for parthenocarpic types, meaning they don’t need bee pollination, which solves the problem of cool temperatures keeping pollinators away during early summer. A variety like Diva or Sweet Success in a five-gallon pot with a small trellis will give you cucumbers from mid-July through September without any hand-pollinating on your part. Summer squash like zucchini needs a big container, at least fifteen gallons, but a single plant of a compact variety like Eight Ball or Astia can be astonishingly productive in just sixty days.

Strategic Placement: Making Every Ray of Sunshine Count

Where you put your containers matters almost as much as what you put in them. In Zone 3, the growing season is short but the summer days are long, often fifteen to sixteen hours of daylight in June and July. Your job is to capture as much of that light and warmth as possible. I arrange my heat-loving containers along the south and west walls of my house, where they get the benefit of reflected warmth off the siding and foundation. A sunny south-facing deck or patio can be twenty-five to thirty degrees warmer than an exposed north-facing spot, which is a staggering difference when you’re counting every heat unit.

I also group my containers together rather than scattering them around the yard. Clustered pots create their own little microclimate, shielding each other from wind and sharing warmth. Think of it like huddling for warmth. On the other hand, my cool-season crops like lettuce and spinach go where they’ll get morning sun but a little afternoon shade, which prevents bolting during those surprisingly warm July days. I’ve learned to watch the shadow patterns on my property throughout the season, noting where the roof line or a nearby tree casts shade at different times of day. A spot that seems perfect in June might be shaded by two in the afternoon come August. Pay attention and move your pots accordingly. That’s the whole beauty of containers.

Extending Your Season on Both Ends

Spring Push: Getting Started Before the Last Frost

The real magic of container gardening in Zone 3 is stretching your growing window beyond that narrow ninety-day slot. On the front end, I start hardening off cool-season container transplants in mid-May, setting them outside during the day and bringing them back inside or into the garage at night. By the time June first arrives, those plants already have two to three weeks of outdoor growth behind them and are far ahead of anything direct-seeded into the ground. For warm-season crops, I use a simple trick that has saved me more times than I can count: I fill black water jugs and place them inside the container ring. They absorb heat all day and release it slowly at night, raising the temperature around the plants by several degrees. Wall-of-Water season extenders work on the same principle, and I use those around my tomato containers from transplant day until mid-June when nighttime temperatures finally stabilize.

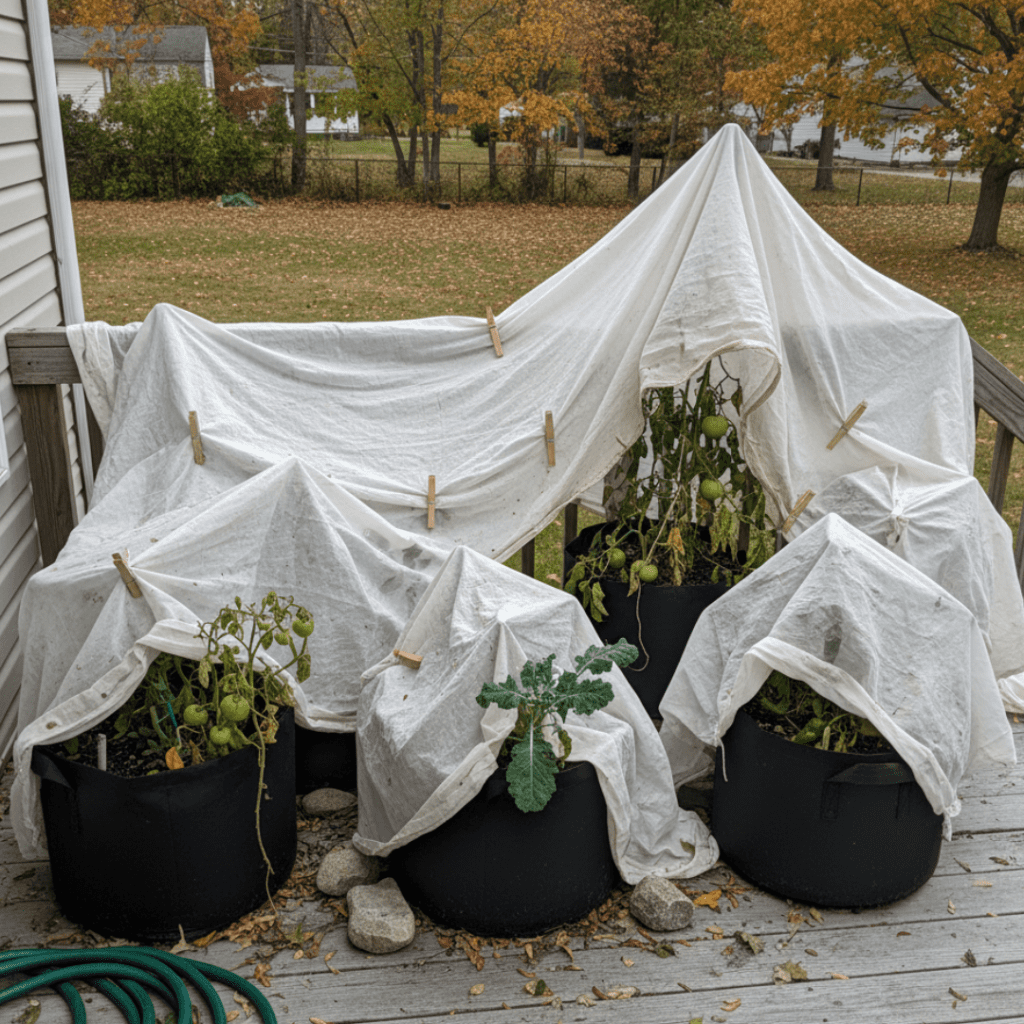

Fall Push: Squeezing Out Every Last Harvest

On the back end, containers give you the ability to react fast when that first frost warning hits in early September. I keep lightweight frost cloth and a few old bedsheets ready to throw over containers on cold nights, and anything on wheels gets pushed against the house wall or into the garage. These simple measures have given me an extra two to three weeks of harvest almost every year. In late August, I also start a second round of quick-maturing crops like radishes, arugula, and Asian greens in fresh containers. These cool-season crops actually taste better after a light frost, and I’ve harvested crisp radishes and peppery arugula well into the first week of October by keeping containers under frost cloth at night. A cold frame placed over a few containers can extend things even further. I’ve kept kale and spinach alive under a simple glass-topped cold frame until late October, long after the in-ground garden has gone to sleep for the winter.

Feeding and Watering in a Short Season

Container plants need more water and more food than their in-ground cousins, and in Zone 3 that’s especially true during the long, warm days of July. I check my containers every single morning and water deeply whenever the top inch of soil feels dry, which in midsummer means nearly every day for large tomato plants. I use a watering wand set to a gentle shower so I don’t blast soil out of the pot, and I always water at the base of the plant rather than over the foliage. Morning watering is ideal because it gives the leaves time to dry before the cool evening temperatures set in, which helps prevent fungal problems.

For feeding, I mix a slow-release organic granular fertilizer into my potting mix at planting time, about two tablespoons per five gallons of soil. Then, starting in early July, I supplement with a diluted liquid fish and seaweed fertilizer every ten to fourteen days. Container soil can’t draw nutrients from the surrounding earth the way garden beds do, so you need to be their sole provider. I’ve found that skipping even two weeks of feeding in the middle of summer can slow fruit production noticeably, especially on heavy feeders like tomatoes and peppers. One more thing: never use garden soil in containers. It compacts, drains poorly, and stays cold longer. A good-quality potting mix with perlite and compost is lighter, warmer, and holds moisture without becoming waterlogged.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I really grow tomatoes in Zone 3 containers?

A: Absolutely. Choose early-maturing varieties like Early Girl or Glacier, start seeds indoors eight to ten weeks before transplanting, use ten-gallon dark containers, and place them against a south-facing wall for maximum warmth. I’ve ripened tomatoes by late August this way for over twenty years.

Q: How early can I move containers outside in Zone 3?

A: Cool-season crops like lettuce, radishes, and kale can go outside in mid-May with frost cloth protection at night. Warm-season crops like tomatoes and peppers should wait until after the last frost, typically around June first, unless you’re using Wall-of-Water protectors.

Q: What size container do I need for vegetables?

A: For tomatoes and peppers, go with ten-gallon containers at a minimum. Lettuce and herbs do well in three- to five-gallon pots. Zucchini and cucumbers need at least fifteen gallons. Bigger is always better for root insulation and moisture retention.

Q: Do containers need to be brought inside during summer frost warnings?

A: Not necessarily inside, but they should be protected. Moving them against the house wall, draping frost cloth over them, or wheeling them into a garage for the night is usually enough to survive a brief dip below freezing.

— Grandma Maggie