I spent my first ten years of gardening guessing what my soil needed, throwing amendments around like confetti and hoping something would work. Some years plants thrived, other years they limped along, and I never quite knew why. Then a fellow gardener convinced me to get a soil test, and it was like someone finally turned on the lights. Suddenly I knew exactly what my soil had, what it lacked, and what to do about it. That twenty-dollar test has saved me hundreds of dollars in wasted amendments and countless hours of frustration. Let me show you how to understand what these tests reveal and how to use that information to build truly productive soil.

Why Soil Testing Beats Guesswork Every Time

Guessing about soil needs wastes both time and money in ways that add up quickly. You might dump lime on soil that’s already alkaline, making problems worse instead of better. You could apply expensive rock phosphate to soil already rich in phosphorus while ignoring a serious potassium deficiency. A proper soil test eliminates this guesswork completely and tells you exactly what your garden needs.

I test every three years as a baseline, but also whenever plants struggle despite seemingly good care. Mysterious yellowing, poor fruiting, stunted growth—these often signal soil imbalances that testing reveals immediately. That small investment prevents an entire season of disappointing harvests and wasted effort.

The basic test costs twenty to thirty dollars through your local extension office or private soil labs. For that modest price, you get detailed information about pH, major nutrients, and usually trace minerals and organic matter content. Some labs offer expanded tests that include micronutrients, heavy metals, or biological activity for slightly more money. I stick with the basic test for vegetable gardens—it provides everything needed for good decision-making.

How to Collect Soil Samples Properly

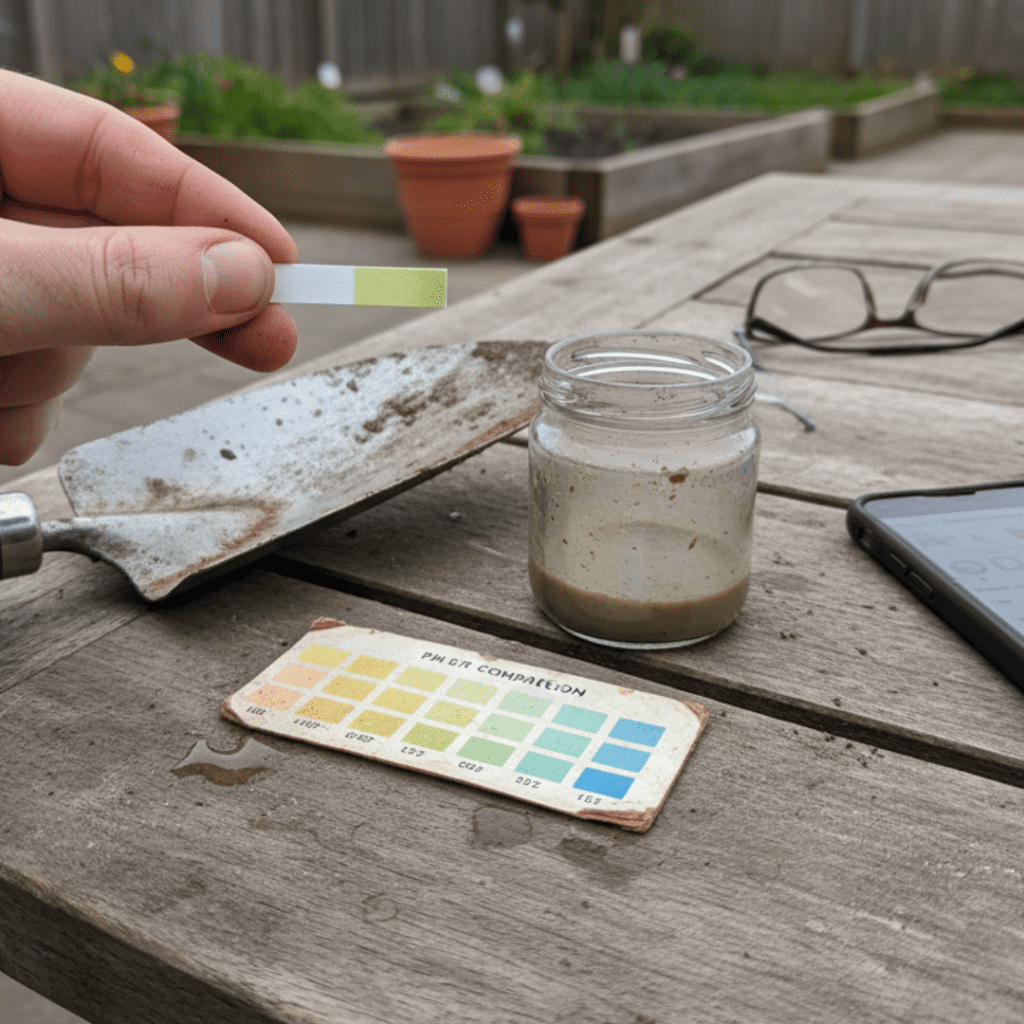

Accurate results require proper sampling technique. Don’t just scoop soil from one spot—you need a representative sample of the entire growing area. I use a clean trowel or soil probe to collect samples from eight to ten locations across each garden bed, taking soil from the top six inches where roots actively feed.

Mix all these samples thoroughly in a clean plastic bucket, then fill the submission container with this blended soil. This composite approach averages out variations and gives you reliable results for the whole bed. Different garden areas with obviously different soil should be tested separately—don’t mix samples from your heavy clay vegetable garden with samples from your sandy herb bed.

Timing matters for accurate testing. I collect samples in fall after harvest but before adding amendments. This shows what the growing season depleted and what needs replenishing. Spring testing works too, but do it early before adding fertilizers that would skew results. Never test immediately after fertilizing or liming—wait at least three months for amendments to incorporate fully.

Let samples dry at room temperature before mailing if the lab requires dry soil. Remove any rocks, roots, or debris. Follow the lab’s instructions exactly for container filling and paperwork—incomplete submissions delay results and waste everyone’s time.

Decoding Your Test Results: The Major Players

Test results measure pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and often trace minerals and organic matter content. Each number tells part of your soil’s story, and understanding what they mean transforms you from someone following orders to someone making informed decisions.

pH comes first on most reports because it controls everything else. This number measures soil acidity or alkalinity on a scale from zero to fourteen, with seven being neutral. Most vegetables prefer pH between 6.0 and 7.0—slightly acidic to neutral. Lower numbers mean acidic soil that needs lime to raise pH. Higher numbers mean alkaline soil that needs sulfur to lower it.

Here’s the critical part about pH: it controls nutrient availability even when nutrients are present in soil. At very low pH, aluminum and manganese become toxic while calcium and magnesium get locked up. At high pH, iron, manganese, and phosphorus become unavailable. Getting pH right unlocks nutrients already in your soil before you add anything else.

Nitrogen levels fluctuate constantly because this element is so mobile and quickly used by plants. Many tests don’t even measure it reliably. I focus instead on building organic matter, which releases nitrogen steadily as it decomposes. Still, very low nitrogen readings warrant immediate attention with blood meal, fish emulsion, or composted manure.

Phosphorus and potassium are more stable and the test captures them accurately. Results typically show as low, medium, or high, sometimes with specific numbers in parts per million. Low phosphorus means poor flowering and fruiting—add bone meal or rock phosphate. Low potassium means weak stems and disease susceptibility—add greensand or kelp meal. High readings mean hold off on these amendments and just maintain with compost.

Calcium and magnesium readings reveal important secondary nutrients. Deficiencies cause specific symptoms—blossom end rot in tomatoes signals calcium shortage, while yellowing between leaf veins suggests magnesium deficiency. Lime adds both calcium and magnesium. Gypsum provides calcium without changing pH.

The Organic Matter Percentage: Your Soil’s Report Card

Organic matter percentage matters as much as any nutrient level, maybe more. This number tells you how much decomposed plant and animal material your soil contains. Good garden soil contains at least five percent organic matter. Most native soils contain one to three percent. Exceptional garden soil reaches eight to ten percent.

When I first tested my main vegetable bed, organic matter came back at two percent. The soil was hard, drained poorly, and needed constant fertilizing. I committed to adding three inches of compost every fall. Five years later, that same bed tested at eight percent organic matter. The transformation was dramatic—loose texture, excellent drainage, far less fertilizer needed, and significantly higher yields.

If your test shows organic matter below five percent, make compost addition your top priority. The recommendations section might list specific fertilizers, and those can help, but without adequate organic matter, you’ll fight an uphill battle forever. Build organic matter first, then fine-tune with amendments.

Following Recommendations While Going Organic

Test results include specific recommendations for your crops and soil type. These are valuable, but they almost always suggest synthetic fertilizers because labs assume most gardeners want quick, cheap solutions. I follow the recommendations but substitute organic alternatives that build soil health instead of depleting it.

When recommendations call for synthetic nitrogen, I apply half the suggested amount using blood meal, feather meal, or alfalfa meal. These organic sources release nitrogen more slowly, so less is needed. They also add other nutrients and support soil biology that synthetic fertilizers kill.

For phosphorus recommendations, I use bone meal or rock phosphate at rates calculated to deliver the same amount of actual phosphorus. The lab report shows recommended pounds per acre or per 1000 square feet—I convert this to the organic product using the nutrient analysis on the package.

Potassium recommendations get filled with greensand, kelp meal, or wood ash. Again, I calculate application rates based on actual potassium content to match what the test recommends.

pH adjustments take months to work fully, so I test in fall and apply amendments for the following spring. Lime to raise pH gets spread in fall at recommended rates and watered in. It can take six months to a year for full pH change. Sulfur to lower pH works faster but still needs three to four months. I retest pH after one season to verify the adjustment worked as expected.

Special Testing Situations Worth Considering

Basic soil tests handle most situations, but some circumstances warrant expanded testing. If you’re gardening on former industrial land or near old painted structures, test for lead and other heavy metals. These contaminants persist indefinitely and can make soil unsafe for food production.

Persistent problems despite correct pH and adequate nutrients might indicate micronutrient deficiencies. An expanded test measuring boron, zinc, copper, manganese, and iron costs slightly more but solves mysterious deficiency symptoms that basic tests miss.

Biological soil tests measure active organism populations and soil respiration. These are newer and more expensive but provide fascinating insights into soil health beyond chemistry. I’ve had one done out of curiosity—it confirmed what I already suspected from observation, but seeing the actual numbers was gratifying.

For most home gardeners, the basic test provides everything needed to make good decisions and improve soil systematically. Spend money on compost and amendments rather than elaborate testing unless you face specific problems that warrant deeper investigation.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I use a home pH test kit instead of lab testing?

A: Home kits measure pH reasonably well but don’t provide nutrient information; use them for quick pH checks between professional tests, but get a full lab analysis every three years for complete information.

Q: My test shows high phosphorus—is too much harmful?

A: Excess phosphorus can lock up other nutrients and contribute to water pollution through runoff; if levels are high, skip phosphorus fertilizers and just maintain with compost until levels normalize.

Q: Should I test every garden bed separately?

A: Test areas with noticeably different soil separately; if your whole garden has similar soil, one composite sample works; different beds with distinct histories benefit from individual testing.

Q: How long after adding amendments should I retest?

A: Wait at least three months for amendments to incorporate fully, preferably one full growing season; testing too soon after adding materials gives inaccurate readings that don’t reflect true soil status.

— Grandma Maggie