It was the last week of May, about twenty-two years ago now, and I had spent the whole morning admiring my young Toka plum — absolutely dripping with tiny green fruitlets, the most promising crop I’d seen in years. By that evening, the temperature had dropped to 26°F. By morning, every single one of those fruitlets had turned black and fallen. I stood there in the garden with my coffee going cold, staring at bare branches, and I learned the most important lesson Zone 4 stone fruit growers ever learn: the calendar means nothing. The weather decides everything. That one night erased an entire season of work. I cried a little, I’ll be honest. Then I went inside, made a fresh pot, and started planning how to never let it happen again. Let me walk you through what fifty years of northern gardening has taught me about growing plums, cherries, and apricots where the winters are long and the springs are treacherous.

Understanding the Zone 4 Stone Fruit Challenge

Stone fruits — plums, cherries, apricots, and their cousins — are not like apples or pears. Apples have the good sense to wait until late spring to bloom. Stone fruits are impatient. They wake up early, push out their blossoms in April or even late March during a warm spell, and then sit there completely exposed when the inevitable cold snap returns. In Zone 4, our average last frost date runs from May 1st to May 15th depending on where you live, and our stone fruits can be in full bloom anywhere from mid-April to early May. You do the math. Those two windows overlap almost every single year.

The biology of it is unforgiving. Once a stone fruit blossom opens fully, temperatures below 28°F will kill it outright — the blossom turns brown from the center out, and whatever embryonic fruit was forming dies with it. Tight, swollen buds that haven’t opened yet can survive down to about 22°F, which gives you a small buffer if a cold snap arrives before bloom peaks. But here’s what I’ve learned after decades of watching weather: a warm week in April gets those buds opening fast, sometimes three to five days faster than you expect. Then a cold front rolls through on May 3rd and it’s over. This is the fundamental challenge of Zone 4 stone fruit, and everything else — variety selection, site choice, frost protection — is about managing that single, annual collision.

Hardy Plums: Your Most Reliable Zone 4 Stone Fruit

The Varieties Worth Planting

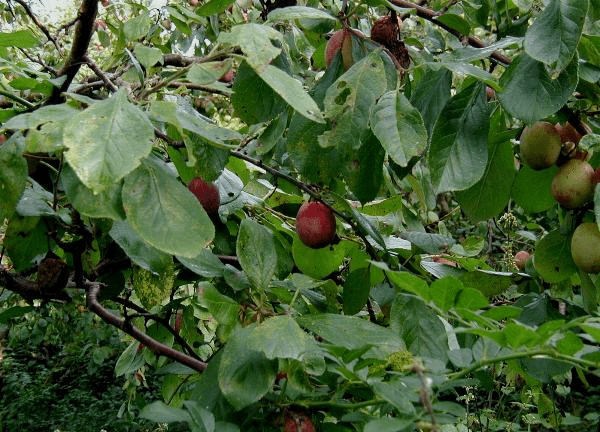

If I had to tell a Zone 4 gardener to plant just one stone fruit and nothing else, it would be the Toka plum. I’ve grown Toka for over thirty years now, and it has earned a permanent place in my heart and my yard. Toka is a hybrid of American and Japanese plum, hardy from Zone 3 all the way to Zone 7, and it produces medium-sized, amber-red fruits with an almost apricot-like sweetness that will stop you in your tracks. The tree reaches 15 to 20 feet at full maturity, though you can keep it closer to 12 feet with annual pruning in late February or early March, before the sap gets moving. Toka blooms slightly later than some other plums — typically early to mid-May in Zone 4 — which gives it just a bit more insurance against the worst spring frosts. It also serves as a pollinator for other plum varieties, which makes it doubly useful in a mixed orchard.

I remember when my neighbor planted a Toka and a Superior plum side by side about fifteen years ago, and the Superior absolutely took off — partly because Toka was right there providing excellent cross-pollination. Superior is another variety I recommend without hesitation, rated for Zone 4 through 8, growing to about 15 feet, with large, deep purple-red fruits that ripen in late August. It’s one of the most productive plums I’ve seen in northern gardens when conditions cooperate. Waneta, another University of Minnesota introduction hardy to Zone 3, produces large, mahogany-red fruits that are excellent for fresh eating and canning, and it ripens a week or so ahead of Superior, which staggers your harvest nicely. La Crescent is the smallest of the group I typically recommend — the fruits are yellow and very sweet, almost honey-flavored — and it’s incredibly cold-hardy at Zone 3 to 7. If you have space for two or three plum trees, a combination of Toka, Superior, and La Crescent will give you cross-pollination, staggered ripening from August into September, and a mix of colors and flavors that makes the whole orchard feel like an accomplishment.

Bush Sour Cherries: The Smart Zone 4 Choice

In my experience, bush sour cherries are the single most practical stone fruit choice for Zone 4 gardens, and I wish someone had told me that forty years ago before I lost two standard-size cherry trees to winter dieback. The Meteor cherry is my first recommendation — it’s hardy from Zone 3 all the way to Zone 8, grows as a true bush reaching 6 to 8 feet tall, and produces bright red, tart cherries that are absolutely perfect for pies, jams, and juice. The University of Minnesota developed Meteor specifically for northern growers, and it shows: this plant is genuinely tough. I’ve seen Meteor bushes come through -35°F winters without significant damage, which is something no standard-size cherry tree can claim.

North Star is another bush sour cherry worth knowing, also rated Zone 3 to 8 and reaching 6 to 8 feet at maturity. North Star produces slightly smaller fruits than Meteor with a very tart, rich flavor — I use North Star cherries for jam almost exclusively because the tartness holds up beautifully against all that sugar. Montmorency is the classic sour cherry, the one you see in most commercial orchards, and it’s rated for Zone 4 to 8. Montmorency grows larger than Meteor or North Star, reaching 12 to 15 feet, which puts it closer to standard tree size, so keep that in mind when planning frost protection. The reason bush cherries are smarter for Zone 4 isn’t just about cold hardiness, though that matters enormously. It’s about management. A 7-foot bush can be completely covered with frost cloth in about ten minutes. A 15-foot tree cannot. Bush cherries also begin fruiting sooner after planting — typically within two to three years versus four to six for standard trees — and the lower profile makes harvest a genuine pleasure rather than a ladder exercise. After fighting with tall trees for decades, I converted most of my cherry planting to bush types, and I haven’t regretted it once.

Hardy Apricots: Worth the Gamble?

I’ll be straight with you about apricots, because I think gardeners deserve honesty more than they deserve false hope. Apricots are the most beautiful, most fragrant, most heartbreaking stone fruit you can plant in Zone 4. When they work — when a warm spring cooperates and your Manchurian Apricot blooms just ahead of the last frost — the fruit is extraordinary. Soft, orange-gold, dripping with a flavor that no grocery store apricot has ever come close to. I’ve had three or four seasons in the past fifty years where my apricot tree produced so abundantly I was giving bags away to everyone in the neighborhood. Those seasons are pure joy. The other seasons — and there are more of them — the blossoms come out in late April, a frost rolls in around May 8th or 10th, and by the next morning it’s done. No fruit. Not even close.

The Manchurian Apricot is the hardiest of the bunch, rated Zone 3 to 6, and it’s the one I’ve grown the longest. It reaches 15 to 20 feet at maturity and produces small, tart fruits that are best for preserves. The Brookcot variety, rated Zone 4 to 7, is a better-tasting fruit with more reliable performance in the warmer end of Zone 4. But if I had to recommend just one apricot for a Zone 4 gardener willing to accept some risk, I’d point you toward Westcot, rated Zone 3 to 7. Westcot was developed in Canada with cold-climate performance specifically in mind, and it blooms slightly later than most apricots — not by much, maybe five to seven days, but in late April and early May that difference can be everything. I’ve seen Westcot produce a crop in years when the Manchurian next to it got completely frosted out. It’s still a gamble, I won’t pretend otherwise, but it’s the most calculated gamble you can make with apricots in Zone 4. Plant it on a sheltered north-facing slope, use frost cloth when buds swell, and accept that some years you’ll get apricots and some years you won’t. The years you do will make it worthwhile.

Beating the Frost: Practical Protection Strategies

After fifty years of fighting late frosts, I’ve settled on a small set of strategies that actually work, and I want to share them plainly without overcomplicating things. The first and most important tool in my arsenal is floating row cover — the frost cloth sold at garden centers in 5-foot and 10-foot widths. For bush cherries and smaller plum trees up to about 10 feet tall, a single layer of 1.5-ounce frost cloth draped over the plant and secured at the base with rocks or landscape staples provides protection down to approximately 26°F. Two layers gets you to around 22°F. I keep 50 feet of frost cloth in my garage from April 1st through May 20th every year, and I’ve learned to throw it on at the first mention of temps below 32°F in the forecast — not 28°F, not 30°F. Below 32°F gets covered. Every time.

Site selection is the other major factor, and it’s the one you can only get right at planting time. I’ve learned to position stone fruits on the north-facing side of a gentle slope whenever possible — what sounds counterintuitive is actually smart cold-air management. A north-facing slope keeps the soil cooler in early spring, which delays bloom by one to two weeks compared to a south-facing location that warms up fast and gets those buds moving too early. Cold air also drains downhill, so avoid planting stone fruits at the bottom of any slope where frost settles on calm spring nights. My best-performing plum tree sits on a gentle northeast-facing rise about 8 feet above the low point of the yard, and I’m convinced that small elevation difference has saved the crop more than once.

One more technique that many gardeners don’t know about: irrigation during frost events. Running overhead sprinklers on blossoms when temperatures drop creates a thin layer of ice that paradoxically protects the tissue inside — the ice formation releases heat energy, holding the temperature at 32°F right at the blossom surface even when air temperature drops lower. Commercial orchardists use this routinely. I run my garden sprinkler on the bush cherry bed from about 11 PM through 5 AM on nights when I’m expecting temperatures between 28°F and 32°F. It does mean a soggy morning and ice-covered plants that look alarming, but the blossoms underneath are almost always fine. Below 28°F, this technique becomes less reliable, and frost cloth is the better choice. Use both together on the coldest spring nights and you’ve done everything that can reasonably be done.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: What is the easiest stone fruit for Zone 4 beginners?

A: Start with a Meteor or North Star bush sour cherry — both are Zone 3 hardy, only 6 to 8 feet tall, self-fertile, and begin fruiting within two to three years. Once you’ve got your frost-management instincts, then branch out to plums and apricots.

Q: Are apricots worth trying in Zone 4?

A: Yes, with realistic expectations — you may get a full crop every three to five years rather than annually, so choose Westcot for the best odds and keep frost cloth ready from late April through mid-May. The seasons when it works produce fruit that justifies every year of waiting.

Q: How do I protect stone fruit blossoms from late frost?

A: Use floating row cover (frost cloth) any night temperatures drop below 32°F — open blossoms die at 28°F, so don’t wait. For larger trees, run overhead irrigation from 11 PM through sunrise to maintain an ice-layer that holds blossom temperature at 32°F.

Q: Which stone fruits are self-fertile and which need pollinators?

A: Bush sour cherries (Meteor, North Star, Montmorency) are self-fertile; hardy plums are generally not and need at least two compatible varieties, with Toka being the best universal pollinator. When in doubt, plant two of anything spaced 15 to 20 feet apart for standard trees or 8 to 10 feet for bush types.

— Grandma Maggie