After fifty years of coaxing life from cold ground, I can tell you that gardening in Zone 3 teaches you patience, persistence, and a healthy respect for frost. My first garden was in northern Minnesota, and I remember standing over those stubborn beds in May, waiting for the soil to thaw while my southern friends were already picking lettuce. It took me a few humbling seasons to realize that fighting the cold was never going to work. What changed everything was learning to work with it. Cold frames, raised beds, and a clever choice of perennial vegetables turned my short season from a frustration into something genuinely productive. If you garden where winter lingers well into spring and sneaks back by mid-September, let me walk you through the strategies that have kept my harvest going strong for decades.

Why Cold Frames Are a Zone 3 Gardener’s Best Friend

A cold frame is, at its heart, a bottomless box with a transparent lid. That simplicity is deceptive because the results are extraordinary. The glass or polycarbonate top traps solar heat during the day and holds it against the cold at night, creating a microclimate roughly one and a half hardiness zones warmer than whatever is happening outside. In practical terms, that means your Zone 3 garden starts behaving more like Zone 4 or even Zone 5 inside that frame. I’ve measured the difference myself on March mornings when the air was sitting at five degrees Fahrenheit and the soil inside the cold frame held at a comfortable twenty-three degrees. That gap is the difference between frozen ground and seedlings quietly putting down roots.

The ideal cold frame for Zone 3 has a back wall about 18 inches tall and a front wall around 12 inches, giving the lid a gentle slope toward the south or southeast. That angle catches the low winter and early spring sun at the best possible angle while letting rain and snowmelt run off. I’ve built mine from reclaimed two-by-twelve lumber with old storm windows as lids, and they’ve lasted over a decade. Position your frame against a south-facing wall of your house or garage if you can. That wall radiates stored heat overnight, giving your plants an extra buffer when temperatures plunge. If you sink the frame about 6 inches into the ground, you gain even more insulation from the surrounding earth.

Building Your Season Extension Strategy

The Zone 3 Growing Window and How to Stretch It

In Zone 3, your last spring frost typically falls around May 15, and the first fall frost arrives near September 15. That gives you roughly four months of frost-free gardening, which feels impossibly short when you have big ambitions. But with cold frames and a few smart techniques, you can start harvesting cool-season crops as early as late March and keep pulling greens well into November or even December. I’ve done it for years, and it never stops feeling like a small miracle to clip fresh spinach while there is snow on the ground around the frame.

The key to understanding season extension in extreme cold is the concept of daylight hours. Once your location drops below about 10 hours of daylight, even the hardiest plants stop growing and go dormant. They do not necessarily die, though. Cold-hardy greens like spinach, mâche, and claytonia can survive freezing temperatures under a cold frame and simply wait in a state of suspended animation until the light returns. In my experience, the dormancy window in Zone 3 runs roughly from early November through early February. During that stretch, I am not growing anything new, but I am still harvesting what matured before the dark period arrived. The trick is getting your fall crops seeded six to eight weeks before the first frost so they reach a good size before dormancy sets in.

Raised Beds: Warming the Soil Where It Counts

Raised beds are another powerful tool for Zone 3 gardens, and they pair beautifully with cold frames. Soil that sits above ground level drains faster and warms more quickly in spring because it is exposed to air and sun on more surfaces than flat ground. In my garden, raised beds filled with a rich compost-and-soil mix are consistently ready to work about two weeks before the in-ground beds. For a Zone 3 gardener, those two weeks are gold. I build my beds 10 to 12 inches tall, which is enough to get meaningful warming without drying out too fast in summer.

You can push the advantage even further by covering your raised beds with clear plastic sheeting three weeks before you plan to plant. I use 6-mil or 10-mil painter’s plastic, weighted down with bricks. The plastic creates a greenhouse effect right at soil level, and I’ve seen bed temperatures jump to 55 or 60 degrees while uncovered beds are still stuck in the low forties. Once you remove the plastic and plant, you can drape lightweight row cover fabric over hoops to keep the warmth going. Combining a raised bed with a cold frame on top is what I call the double-layer approach, and in Zone 3 it turns an early April planting from reckless to reasonable. Position those beds with the long side facing south, and you will catch every ray of sun available during those short spring days.

What to Grow: Cold Frame Crops for Zone 3

Not every vegetable thrives in a cold frame during frigid conditions, so choosing the right crops matters. In Zone 3 winters, there are about five crops you can dependably harvest through the coldest months under a cold frame: spinach, scallions, mâche, claytonia, and carrots. Mâche is the toughest of the group and will hold up even during the deepest cold spells. For fall and early spring growing, your options expand to include lettuce, kale, radishes, arugula, and beets. I plant my fall cold frame crops around mid-August, which gives them roughly six to eight weeks of solid growing time before the first hard freeze. They reach a nice harvesting size by mid-October, and from that point on, the cold frame simply preserves them.

One thing I learned the hard way is that cold frames can overheat on sunny days, even in March. When the sun hits that glass and the air inside climbs past 60 degrees, your tender greens can cook before you realize what has happened. I prop my cold frame lids open with a notched stick on any day the temperature rises above 40 degrees outside, and I close them back up by mid-afternoon. You can also buy automatic vent openers that use a wax cylinder to lift the lid as temperatures rise. After losing a beautiful crop of lettuce to one unseasonably warm afternoon about fifteen years ago, I decided that investment was well worth the twenty dollars.

Perennial Vegetables: Plant Once, Harvest for Years

The Perennial Backbone of a Zone 3 Garden

While cold frames handle your annual crops, perennial vegetables form the backbone of a truly resilient Zone 3 food garden. These are plants you put in the ground once, and they reward you for years, sometimes decades, with minimal fuss. In a climate where every growing day is precious, I cannot overstate how valuable it is to have food producing itself without a single seed packet or transplant each spring. The three most reliable perennial vegetables for Zone 3 are rhubarb, asparagus, and sorrel, and I grow all three.

Rhubarb is perhaps the most foolproof perennial you can grow in a northern garden. It actually needs a long, cold winter dormancy period to produce well, which means Zone 3 is practically ideal for it. Plant divisions in a sunny, well-drained spot with at least 3 feet of space in every direction, and resist the urge to harvest much during the first year. By the second or third season, you will have a vigorous plant that produces thick, tart stalks from late spring through summer. My current rhubarb came from a division that had been passed through three generations of a neighbor’s family. It is over forty years old by lineage and shows no sign of slowing down. Just remember that only the stalks are edible. The leaves contain high levels of oxalic acid and should always go to the compost pile, never the kitchen.

Asparagus takes patience. You will need to wait two to three years after planting crowns before you can harvest freely, and you should resist cutting any spears the first year. But once an asparagus bed is established, it can produce for 15 to 20 years or longer. I harvest spears when they are about 6 inches above the soil line, snapping or cutting them just below ground level. The harvest window lasts roughly six weeks each spring, after which you let the remaining shoots grow into their feathery ferns that feed the roots for next year. Varieties like Jersey Knight and Mary Washington have proven themselves in Zone 3 gardens over many years. An asparagus bed is a genuine long-term investment, and in my opinion, the flavor of fresh-picked asparagus compared to anything from a grocery store is reason enough to wait those first few years.

Sorrel: The Overlooked Early Spring Star

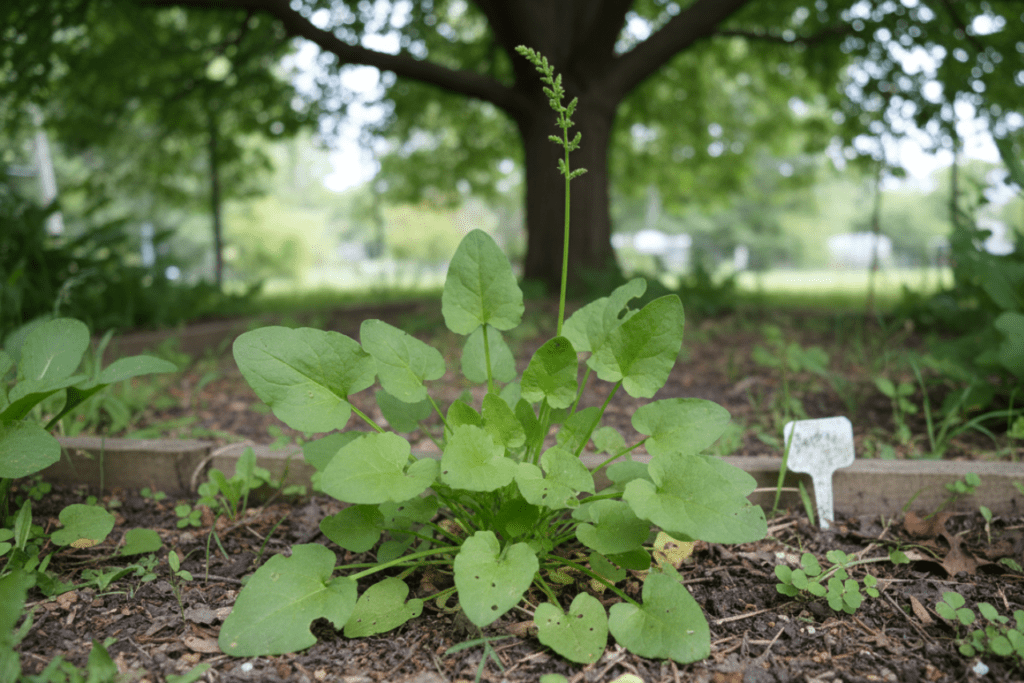

Sorrel deserves far more attention than it gets, especially in cold-climate gardens. It is one of the very first greens to push through the soil in spring, often weeks before any annual seedling has even been planted. French sorrel is my favorite variety for its bright, lemony flavor that livens up salads and makes a wonderful soup. The leaves are somewhat similar to spinach in appearance but carry a pleasant tartness that pairs beautifully with eggs, fish, and potatoes. I grow my sorrel under a semi-shaded spot beneath the edge of an apple tree, and it does not mind one bit. In fact, sorrel tolerates partial shade quite well, making it perfect for those garden corners that do not get a full six hours of sun.

To keep sorrel productive, snip off the flower stalks as they appear throughout the season. If you let it go to seed, the plant puts its energy into reproduction instead of leaf production, and the leaves turn bitter. With regular harvesting and deadheading, a single sorrel plant will produce tender greens from April through October in Zone 3. It needs about an inch of water per week, tolerates a range of soils, and can be started from seed or by dividing an existing clump. I divide mine every three to four years and share the extras with anyone who will take them. Sorrel is not as long-lived as rhubarb, but starting new plants from seed is easy, and some gardeners simply treat it as a self-sowing annual that happens to survive the winter.

Putting It All Together: A Zone 3 Season Extension Plan

After years of experimenting, here is what works best in my Zone 3 garden. In late February or early March, I lay clear plastic over my raised beds to start warming the soil. By mid to late March, I seed my cold frames with spinach, mâche, and lettuce. Around April, once soil temperatures in the raised beds reach the mid-forties, I direct-sow peas, radishes, and early carrots under row cover. The perennials, sorrel and rhubarb, are already growing on their own by then. Once the last frost passes around May 15, I transition the cold frames to hardening off my indoor-started tomatoes and peppers before they go into the open garden.

On the other end of the season, I seed another round of cold-hardy greens into the cold frames in mid-August. These reach good size before the first frost in September and continue growing through October. By November, when daylight drops below 10 hours, growth stops, but the plants survive under the cold frame glass, waiting patiently for harvest. Adding a layer of heavy row cover fabric inside the cold frame provides additional insulation that can keep greens alive through temperatures well below zero. I have picked fresh spinach in December this way, and honestly, there is nothing quite like it. The flavor of cold-sweetened greens, where the plant converts starches to sugars as a natural antifreeze, is better than anything you will taste in summer.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: How much does it cost to build a basic cold frame?

A: Using reclaimed lumber and an old storm window, you can build a solid cold frame for under thirty dollars. Even buying all new materials, a 3-by-6-foot frame rarely costs more than sixty to seventy-five dollars.

Q: Can I grow tomatoes in a cold frame in Zone 3?

A: Cold frames are best for cool-season crops like greens and root vegetables. Tomatoes need consistent warmth and space that a cold frame cannot provide, so start those indoors and transplant after the last frost.

Q: Do I need to water plants inside a cold frame during winter?

A: Very little. Watering is needed occasionally through fall, but once winter dormancy sets in, the plants require almost no water until light and temperatures increase again in late winter.

Q: How long before I can harvest asparagus after planting?

A: Plan on waiting two to three years before taking a full harvest. Cut sparingly in the first year and allow the ferns to develop strong roots that will feed production for the next fifteen to twenty years.

— Grandma Maggie