I still remember the look on my daughter’s face the first time I told her I was keeping worms under my kitchen sink. She thought I’d finally lost it. But after fifty years of composting every way imaginable—hot piles, cold piles, tumblers, trenches—I can tell you that nothing converts kitchen scraps into rich, dark plant food faster or more quietly than a small bin of red wigglers tucked into a cabinet. My little under-sink bin has been running for over twelve years now, and it handles every banana peel, coffee filter, and lettuce stub my kitchen produces without a whisper of odour. If you’ve ever wanted to compost but thought you needed a big backyard pile, let me show you how a shoebox-sized worm colony can do the job right where you cook.

Why Red Wigglers Make the Best Indoor Composters

Not all worms are created equal, and this is a lesson I learned the hard way. In my twenties, I scooped a cup of fat nightcrawlers out of my garden and dropped them into a bucket of food scraps, thinking I’d invented indoor composting. Every last one of them died within a week. The problem was species. Nightcrawlers are deep burrowers that need cool, compacted soil. Red wigglers—Eisenia fetida, if you want the fancy name—are surface dwellers that naturally live in decaying leaf litter and organic debris. They stay in the top three to eight inches of material, which is exactly the depth of a small bin. They thrive at room temperature, they tolerate crowding remarkably well, and a healthy population can consume roughly half its body weight in food scraps every single day. One pound of red wigglers—around eight hundred to a thousand individuals—is enough to start a productive under-sink bin, and they’ll double their numbers in about sixty to ninety days if conditions are right.

Setting Up Your Under-Sink Worm Bin

Choosing the Right Container

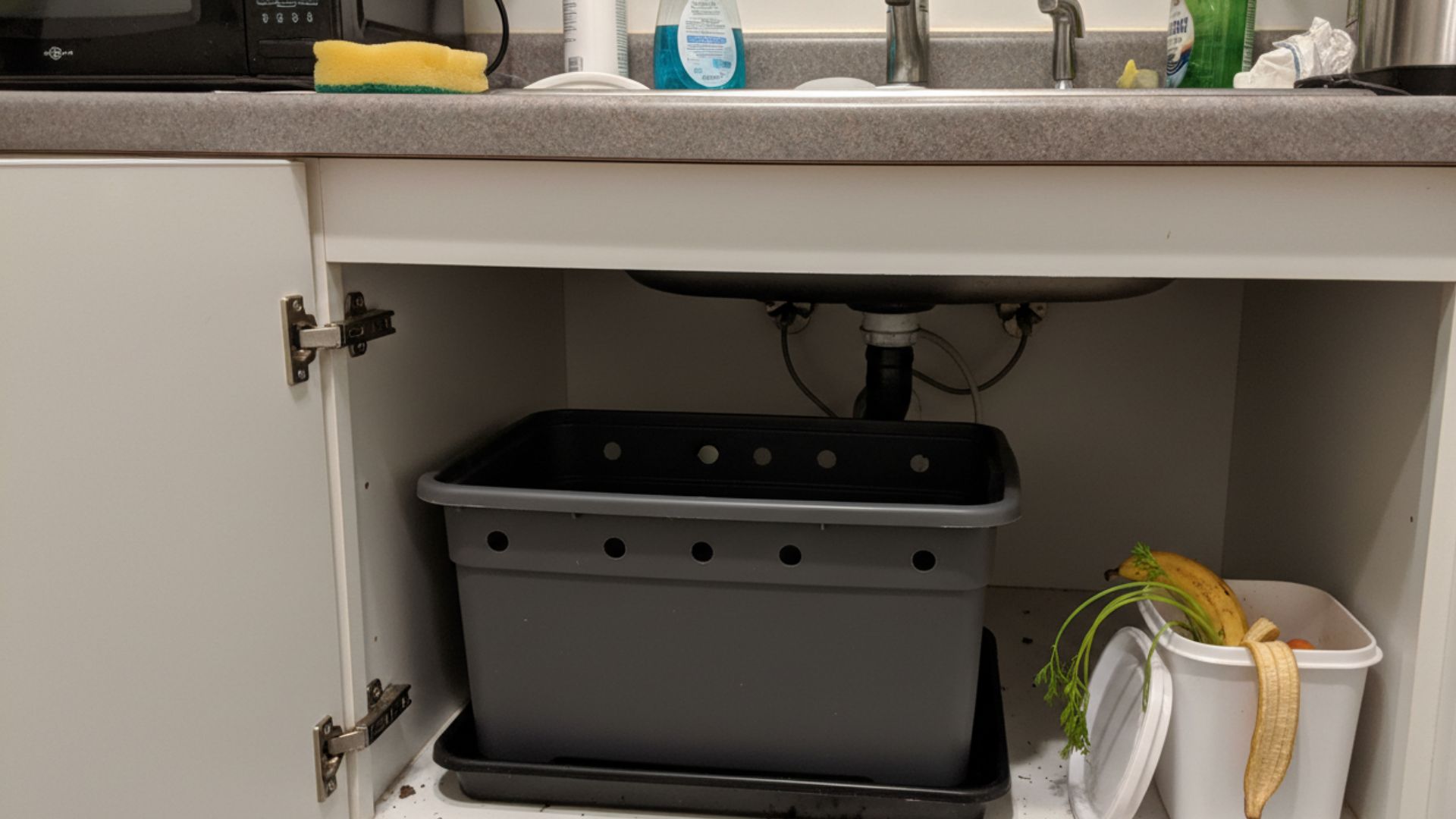

You don’t need anything expensive or fancy to get started. My favourite beginner bin is a standard ten-gallon opaque plastic storage tote—the kind you can pick up at any hardware store for a few dollars. It needs to be dark-coloured because red wigglers are extremely sensitive to light and will burrow away from it, which actually works in your favour for keeping them inside. The ideal dimensions for an under-sink setup are roughly twenty-four inches long by sixteen inches wide and eight to twelve inches deep. Measure the cabinet space under your sink first, then find a tote that fits comfortably with an inch or two of clearance on each side for airflow.

Ventilation is the single most important detail. I drill rows of small holes—about one-sixteenth of an inch—across the bottom every two to three inches for drainage, then drill quarter-inch holes around the upper sides of the bin for air exchange. Set the bin on top of a shallow tray or a second lid to catch any moisture that drains through. In over a decade of running my kitchen bin, that tray has never collected more than a tablespoon or two of liquid between harvests, so don’t worry about mess. If you’d rather skip the drilling, commercial stacking tray systems like the Worm Factory 360 work beautifully and fit under most standard sinks, though they’ll cost you around forty to sixty dollars compared to five dollars for a plastic tote.

Building the Perfect Bedding

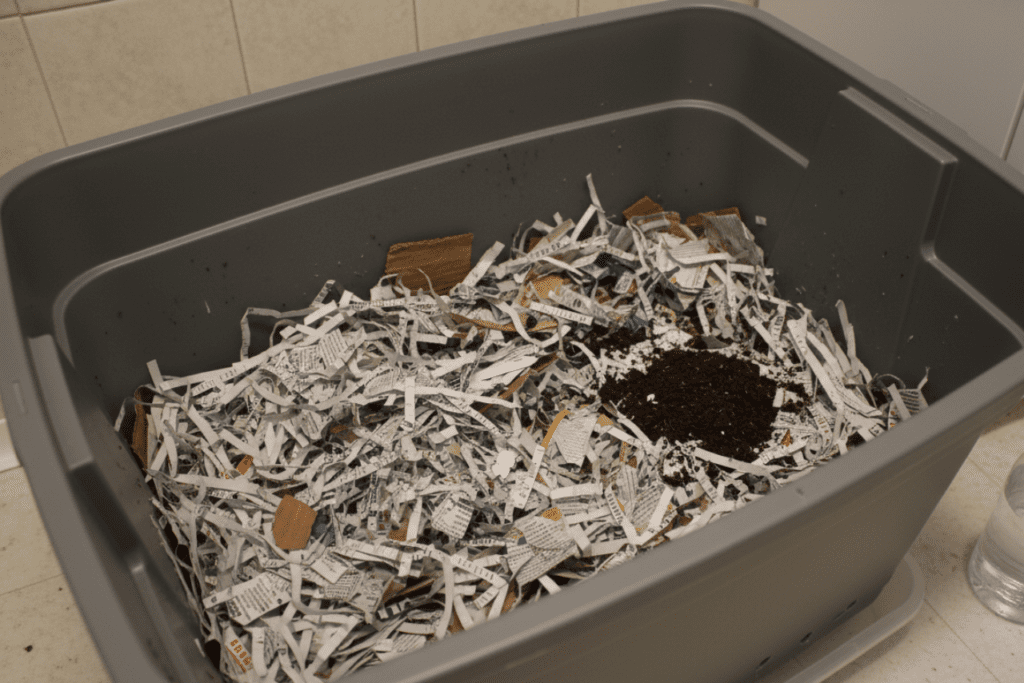

Think of bedding as your worms’ home, their blanket, and their slow-release meal all rolled into one. I use shredded newspaper as my base—plain black-and-white newsprint torn into strips about one inch wide and six to eight inches long. You can also use shredded corrugated cardboard, brown paper bags, or shredded egg cartons, and I often mix two or three of these together for a nice variety of textures. Avoid anything glossy, bleached, or waxy. Fill your bin about two-thirds full with loosely fluffed bedding, then dampen it with dechlorinated water until it feels like a well-wrung sponge. When you squeeze a handful as hard as you can, you should get barely one drop of liquid. That sixty to seventy percent moisture level is the sweet spot.

Before adding your worms, I like to toss in a couple of handfuls of plain garden soil or finished compost. This introduces beneficial microbes and gives the worms grit for their gizzards, which helps them grind up food. A couple of tablespoons of crushed eggshell does the same job and keeps the bin’s pH in the slightly acidic range—around 6.0 to 7.0—where wigglers are happiest. Once the bedding is moist and fluffy, spread your pound of red wigglers on top, leave the lid slightly ajar with a light on overhead, and walk away. The worms will burrow down into the dark bedding within an hour. Keep that lid snug for the first three to seven days, because new worms are restless travellers until they settle into their surroundings.

What to Feed Your Worms (And What to Keep Out)

Red wigglers will happily eat almost any plant-based kitchen scrap you give them. Vegetable trimmings, fruit peels, coffee grounds and unbleached filters, tea bags, stale bread, corn cobs, and wilted salad greens are all fair game. I keep a small container with a lid next to my cutting board and toss scraps in throughout the day, then bury them in the bin every two or three days. Chopping scraps into smaller pieces—roughly half-inch chunks—speeds up decomposition dramatically because it gives the microbes and worms more surface area to work on. Some folks even freeze their scraps overnight and then thaw them before feeding, which breaks down cell walls and makes everything softer for the worms.

Now here’s the list that will save you from every smelly disaster I’ve ever encountered: never add meat, fish, dairy, oils, butter, or heavily salted foods. These attract pests and create anaerobic conditions that will make your bin reek. Go easy on onion, garlic, and citrus peels—a little is fine, but a whole bag of orange rinds will crash the pH and drive your worms to the edges of the bin. I also learned the hard way that too much broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower will create a sulphurous stench that no amount of fresh bedding can mask. The golden rule I’ve followed for years is to add roughly a two-to-one ratio of fresh bedding to food scraps by volume every time you feed. That extra carbon keeps moisture balanced and odour non-existent.

Harvesting and Using Your Worm Castings

When and How to Harvest

After about eight to twelve weeks, the bottom of your bin will be filled with dark, crumbly, earthy-smelling material that looks nothing like the newspaper and scraps you started with. That’s vermicompost—often called black gold by gardeners, and for good reason. Those castings contain roughly five times more nitrogen, seven times more phosphorus, and eleven times more potassium than average garden soil, plus a thriving community of beneficial microbes that suppress plant diseases.

My favourite harvesting method is simple and low-tech. I push all the bin contents to one side, then fill the empty half with fresh, moist bedding and a small amount of food scraps. Over the next two to three weeks, the worms will migrate toward the fresh food, leaving the finished castings behind for easy scooping. If you’re in a hurry, dump everything onto a plastic sheet under a bright lamp. The worms will burrow away from the light into the centre of the pile, and you can scrape finished castings off the outer edges every twenty minutes or so until you’re left with a tight ball of worms ready to go back into fresh bedding. I harvest my under-sink bin about four times a year and get roughly five to six pounds of finished castings each time—more than enough to feed all my seedlings and container plants.

Troubleshooting the Most Common Worm Bin Problems

After all these years, I can diagnose most bin problems with my nose and my eyes in about thirty seconds. A healthy worm bin smells like damp forest floor after a rain—earthy and clean. If you detect a sour or rotten smell, you’ve almost certainly overfed or the bin is too wet. Stop feeding for a full week, add several inches of dry shredded newspaper on top, and leave the lid slightly cracked for better airflow. Things will right themselves within days.

Fruit flies are the other complaint I hear most often, and they’re entirely preventable. Always bury food scraps at least two inches under the bedding surface, and keep a thick layer of dry newspaper or cardboard on top as a barrier. If flies have already moved in, a small dish of apple cider vinegar with a drop of dish soap set next to the bin will catch them within a couple of days. Worms trying to escape usually signals a temperature or moisture problem—check that the bin isn’t too hot, too wet, or too acidic from an excess of citrus or brassica scraps. I keep a cheap soil thermometer clipped to my bin and glance at it every time I open the cabinet. As long as the reading stays between 55 and 77 degrees, my wigglers are content. In summer, if your under-sink area runs warm, a frozen water bottle set on top of the bedding for a few hours will bring temperatures down gently without shocking the worms.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Will a worm bin under my sink smell bad?

A: A properly managed bin has no noticeable odour at all—it smells like damp earth. Odour only develops when you overfeed, add the wrong foods, or let moisture build up without enough dry bedding.

Q: How many worms do I need to start?

A: One pound of red wigglers—roughly eight hundred to a thousand worms—is perfect for a standard ten-gallon bin. They’ll double their population in about sixty to ninety days.

Q: Can I use regular earthworms from my garden instead of red wigglers?

A: No. Garden earthworms are deep-burrowing species that need cool, compacted soil and will not survive in a shallow indoor bin. You specifically need Eisenia fetida, which are sold online and at bait shops.

Q: What do I do with the worm bin when I go on vacation?

A: Give the worms a good feeding and add a thick layer of damp bedding before you leave. A healthy bin can go two to three weeks without attention, so most vacations are no problem at all.

— Grandma Maggie