I’ll never forget the look on my neighbor’s face when she saw me hauling bare-root apple trees into my yard during a Minnesota spring, the last snow still clinging to the fence posts. “Maggie,” she said, shaking her head, “fruit trees can’t survive out here.” That was thirty-five years ago. Those same trees are still standing, and every September they give me more Haralson apples than I can eat, bake, and give away combined. The truth is, Zone 3 gardeners have been told for far too long that fruit growing isn’t for them. I’m here to tell you that’s nonsense. You just need the right varieties, a little patience, and a few tricks I’ve picked up over the decades. Let me walk you through exactly which fruit trees will not only survive where temps hit minus forty, but actually reward you with bushels of homegrown fruit.

Why Zone 3 Fruit Growing Is Absolutely Worth Your Time

Zone 3 means your winter lows can plunge to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and that’s not the windchill—that’s the actual air temperature. It sounds brutal, and it is. But here’s what most people don’t realize: cold-hardy fruit trees actually need those frigid winters. Apple trees, for instance, require between 500 and 1,000 chill hours below 45 degrees Fahrenheit to break dormancy properly and set fruit the following spring. In Zone 3, you’ve got chill hours to spare. The real challenge isn’t the cold itself—it’s choosing varieties that were specifically bred or selected to handle it. Over a century of breeding work at experimental farms across Minnesota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and beyond has given us cultivars that laugh at minus forty. These aren’t scraggly trees producing tiny, bitter fruit either. I’m talking about full-sized, delicious apples, sweet-tart cherries, and fragrant plums that hold their own against anything from a milder climate.

Cold-Hardy Apples: Your Best Bet in Zone 3

If you’re going to plant one fruit tree in Zone 3, make it an apple. Apples offer the widest selection of cold-hardy cultivars by far, and I’ve grown more varieties than I can count on both hands. The key is choosing cultivars grafted onto hardy rootstock, because even a tough apple variety can fail if the roots underneath it can’t take the cold.

My top recommendation for Zone 3 is Haralson, developed right in Minnesota and still one of the most reliable producers I’ve ever grown. It ripens in mid-September, stores beautifully for months in a cool cellar, and makes the best pie you’ll ever taste. Honeycrisp is another winner that most people recognize from the grocery store—it was also developed by the University of Minnesota specifically for cold hardiness and outstanding flavor. It needs between 700 and 1,000 chill hours and typically bears fruit about three years after planting. Wealthy is an heirloom variety that I’ve seen thrive in the coldest corners of Zone 3, producing medium-sized apples that are wonderful for sauce and fresh eating alike.

Other proven Zone 3 apple varieties include Beacon, Duchess of Oldenburg (a gorgeous heirloom that ripens early in September), State Fair, Snow, and Norkent, which has a lovely pear-like flavor reminiscent of Golden Delicious. For smaller spaces, KinderKrisp is a compact tree from Fairhaven, Minnesota, that produces small, crisp apples children love. Every apple tree needs a pollinator blooming at the same time, so always plant at least two different varieties. If space is tight, a hardy crabapple like Dolgo makes an excellent pollinator—it blooms prolifically and produces tart fruit that’s wonderful for jelly and adds a beautiful pink tinge to homemade applesauce.

Sour Cherries That Thrive Where Sweet Ones Can’t

I’ll be honest with you: sweet cherries are a tough sell in Zone 3. Most varieties simply can’t handle the cold, and even the hardier ones are gambles. But sour cherries—also called pie cherries or tart cherries—are a different story entirely, and I think they’re one of the most underappreciated fruits for cold-climate gardens.

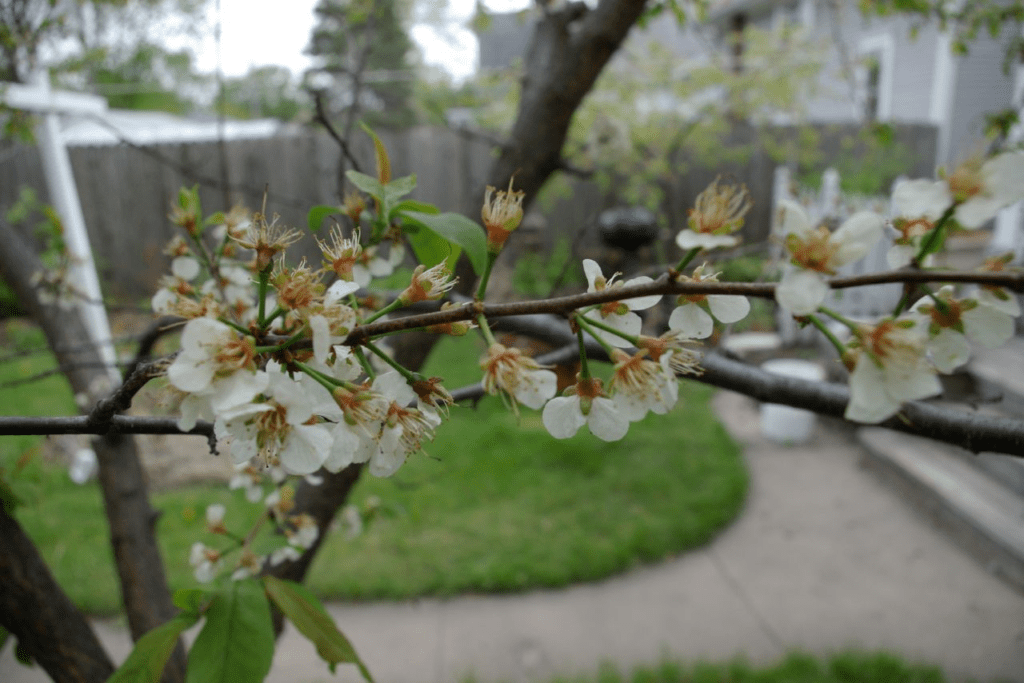

Sour cherries bloom a bit later than sweet types, which means they’re less likely to lose their flowers to a late spring frost—and that alone makes them more dependable in our short-season gardens. They’re also self-pollinating, so you can plant just one tree and still get fruit, though I always recommend planting two for heavier yields.

My favorite for Zone 3 is Carmine Jewel, a bush-type cherry developed at the University of Saskatchewan. It grows to about seven feet tall, which means no ladder needed, and it produces deep red cherries that ripen in July. It’s one of the few cherries truly rated for Zone 3, and after three to five years of establishment, it yields generously. North Star is another excellent choice—a naturally dwarf tree staying around eight to ten feet that the University of Minnesota introduced back in 1950. It’s disease-resistant, especially against brown rot and leaf spot, and produces beautifully tart fruit perfect for pies and preserves. Meteor is a semi-dwarf reaching ten to fourteen feet with large, mildly acidic fruit, and Evans Bali is a reliable producer with decent-sized bright red cherries that make gorgeous preserves. Don’t let the word “sour” scare you—when these cherries are left to ripen fully on the tree, many of them develop a sweetness that surprises people. And for baking? Nothing compares.

American Plums and Hardy Hybrids Worth Planting

Plums are where things get interesting in Zone 3, because you have two distinct paths: native American plums and Japanese-American hybrids. The native American plum (Prunus americana) is an incredibly tough tree that grows wild across the northern plains, reaching fifteen to twenty-five feet tall and tolerating everything from sandy soil to heavy clay. The fruit is smaller than what you’d find in a grocery store—red or yellow with a tart flavor—but it makes some of the finest jam and preserves you’ll ever put up. I’ve had a row of them along my back fence for over twenty years, and they’ve never failed me through even the worst winters.

For larger, sweeter fruit, look to the Japanese-American hybrids that breeding programs in Minnesota and the Dakotas developed. Alderman, released in 1985 by the University of Minnesota, is hardy to Zone 3 and produces beautiful plums on a compact twelve-foot tree. Toka, sometimes called the bubblegum plum for its sweet fragrance, is a vigorous hybrid that also serves as an outstanding pollinator for other plum varieties. Waneta has been considered one of the finest American plums for over a century, producing medium-large fruit with red skin and sweet yellow flesh. Brookgold is a gold-skinned freestone plum that ripens in August on a tidy twelve-foot tree. One important note: plum pollination is trickier than apples. Japanese-type plums need another Japanese or hybrid plum nearby, while American plums need another American variety. A Nanking cherry can also serve as a cross-pollinator for Japanese-type plums in a pinch. Plan for at least two compatible trees, spaced fifteen to twenty feet apart.

Setting Your Trees Up for Success in Extreme Cold

Microclimates and Site Selection Make All the Difference

Choosing the right variety is only half the battle. Where you plant that tree on your property matters just as much as what you plant. After fifty years, I can tell you that the difference between a south-facing slope and a low-lying pocket in your yard can mean the difference between a freezer full of fruit and a dead tree. South-facing spots near buildings absorb heat during the day and release it slowly at night, creating a protective buffer of a few critical degrees. Avoid low spots where cold air settles like water pooling in a bowl—I’ve lost more than one promising tree to a frost pocket I should have known better about.

Wind protection is equally important. A windbreak of evergreens or even a solid fence on the north and west sides of your planting area can dramatically reduce winter damage to branches and flower buds. I planted a row of arborvitae on the windward side of my little orchard about twenty years ago, and the difference in fruit set has been remarkable ever since. If you don’t have a windbreak established yet, a temporary fence of burlap or lattice with about fifty percent permeability works well while your living windbreak fills in. Apply three to four inches of mulch in a circle around each tree’s base before the ground freezes, keeping the mulch pulled back two to three inches from the trunk to prevent rot and rodent damage. And stake your newly planted trees—that first winter, wind rocking the trunk will tear the tender new root hairs right out of the soil before they can establish.

Planting, Patience, and the First Few Years

In Zone 3, I always recommend spring planting for fruit trees—get them in the ground as soon as the soil is workable and thawed, while the trees are still dormant. Dig your hole twice as wide as the root system and plant at the same depth the tree grew in the nursery. Water deeply at planting and continue watering thoroughly once a week through that first growing season. I like to give my newly planted fruit trees a dose of balanced fertilizer in early spring, but go easy—over-fertilizing pushes soft, leggy growth that’s more vulnerable to winter kill.

Now here’s the part nobody wants to hear: patience. Most fruit trees in Zone 3 take three to six years to produce their first real harvest, and some stone fruits like cherries can take up to seven. I know that feels like forever when you’re staring at a bare whip of a tree in your yard. But those years of root establishment are building the foundation for decades of production. My oldest apple trees are pushing thirty-five years old and still producing heavily. Baby your trees in those first few seasons with consistent water, a light hand on the pruner, and good mulch, and they’ll reward you for a lifetime.

Bonus Fruits for the Adventurous Zone 3 Gardener

Once you’ve got your apples, cherries, and plums established, don’t stop there. Honeyberries (also called haskaps) are one of my newest favorites—they’re hardy to Zone 2, produce blueberry-like fruit that ripens before strawberries, and their blooms are frost-resistant. They taste like a cross between a blueberry and a grape, and they need almost no fussing beyond a second bush for pollination. Hardy pears like Golden Spice are thorny but tough to Zone 3, producing small golden fruit perfect for canning and preserves. And don’t overlook hardy grapes—seeded varieties can survive Zone 3 winters when planted in a sheltered south-facing spot protected from north winds. I’ve even seen gardeners in Alberta and Saskatchewan getting reliable grape harvests with a bit of winter wrapping in burlap. The world of cold-climate fruit is bigger than most people imagine, and it grows every year as breeders keep pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

Quick-Fire FAQ

Q: Can I really grow apples where it hits minus forty?

A: Absolutely. Varieties like Haralson, Honeycrisp, Wealthy, and Norkent were specifically developed for these conditions and have proven track records in Zone 3 gardens across the upper Midwest and Canadian prairies.

Q: Do I need to plant more than one fruit tree to get fruit?

A: For apples and plums, yes—you need at least two compatible varieties for cross-pollination. Sour cherries like Carmine Jewel and North Star are self-pollinating, so one tree can produce on its own, though two will give you heavier yields.

Q: How long before I get my first harvest?

A: Most apple trees bear within three to five years of planting, sour cherries in three to five years, and plums in three to six years. Dwarf and semi-dwarf types often produce a year or two sooner than standards.

Q: What’s the single most important thing I can do to protect my fruit trees in Zone 3?

A: Choose a sheltered planting site with full sun, wind protection on the north and west sides, and good air drainage so cold air doesn’t pool around the trunk. That alone will make more difference than any other single practice.

— Grandma Maggie